Density seems to be more of a scapegoat than the cause of increasing virus transmission at the city level

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has triggered an unprecedented upheaval in the economic and social lives of people the world over. No one knows what the end will look like. For emerging economies like India — my home country — cities held promise for future jobs and became magnets for migrants and investors.

The larger and denser a city became, the more its productivity rose and created wealth and migrants. The importance of managing density for public health and efficient energy use thus became a primary task for local leaders and urban professionals.

But the spread of COVID-19 in cities now raises questions about density and its role in transmitting the infection, although there are many unknowns, while the virus that causes COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to spread. Let’s take a snapshot of our current understanding of how density plays a role in the spread of COVID-19.

Are cities victims or spreaders?

Cities bring people together to create vibrant markets. Dense and large cities nurture economic prosperity by facilitating efficient social and economic interactions and knowledge-sharing between people.

But now, some see density as the reason for the spread of SARS-CoV-2 since it increases the potential for person-to-person contact. It is an intuitive reflection but fails to explain why the incidences of COVID-19 vary between cities, despite the same city-level densities.

A look at the relation between the reported number of COVID-19 affected cases per thousand people in Indian cities of over half a million size and their population densities, as of May 4, 2020, suggested city densities had insignificant impact on rates of virus infection. Density seems to be more of a scapegoat than the cause of increasing virus transmission at the city level.

Relation between city density, COVID-19 cases

Source: Density and population: Goel R. & Mohan D. Investigating the association between population density and travel pattern in Indian cities – An analysis of 2011 census data, Cities 100 (2020) 102656, Elsevier

But why has the virus overwhelmed western and central Indian cities and left others? Is it demography, pre-existing conditions or the speed of government response that caused such a variation?

There are many unknowns but the stories of early detected cases suggest SARS-CoV-2 reached India through travellers, migrants and tourists coming to international gateway cities Mumbai and Delhi from west Asia, Europe and cities in the United States.

From these gateway cities, the airborne fast-transmitting virus began its journey to other Indian cities and towns. The density of big cities was a primary attractor of virus carriers, because of which SARS-CoV-2 was transmitted first within cities and then to other cities, before the Union government invoked the nationwide lockdown.

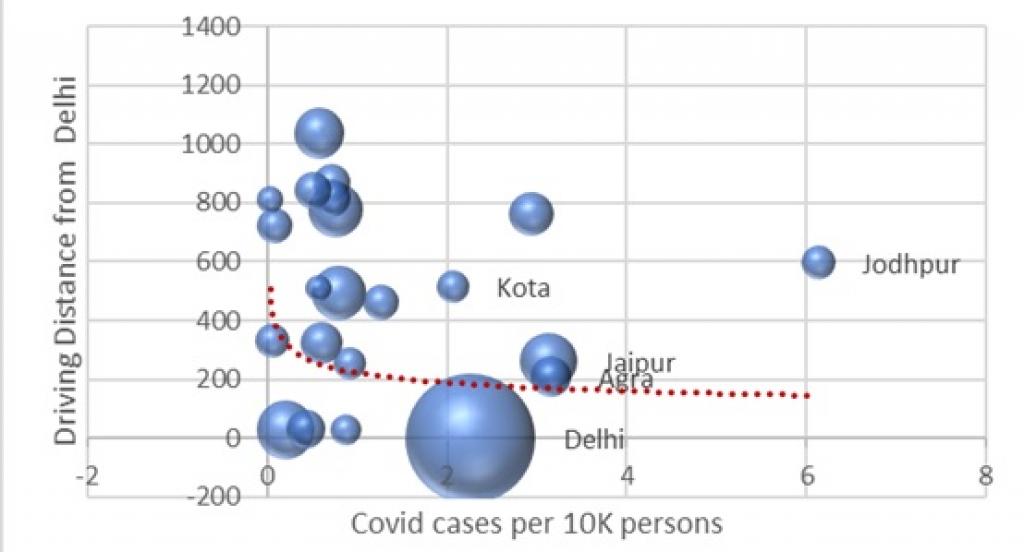

A look at the level of infection in cities within 1,000 kilometres of Mumbai and Delhi suggest the lockdown and its timing seem to have curtailed the virus transmission beyond 200 km from both cities.

COVID-19 cases in cities within 1,000 km from Delhi

Source: Density and population: Goel R. & Mohan D. Investigating the association between population density and travel pattern in Indian cities – An analysis of 2011 census data, Cities 100 (2020) 102656, Elsevier

COVID-19 cases in cities within 1,000 km from Mumbai

Source: Density and population: Goel R. & Mohan D. Investigating the association between population density and travel pattern in Indian cities – An analysis of 2011 census data, Cities 100 (2020) 102656, Elsevier

A few cities in western, central and southern India, however — including Ahmedabad, Indore, Jodhpur and Vijayawada — were severely affected compared to others, raising the question as to why this occurred.

A single affected person is enough to trigger an exponential rate of spread, depending upon his / her contact rate and exposure time with susceptible people in the population — including the elderly, diabetic, asthmatic, etc — according to epidemiologists.

These conditions vary widely within cities, with the spread exacerbated by overcrowded living particularly in informal settlements and slums.

For the same density, residents of slums and high-rise apartment complexes suffer differently. Unlike the high-rise enclave, dwellers in horizontally spread slums endure overcrowded living with lack of open spaces for recreation, amenities and circulation.

The need for maintaining physical distance during the pandemic becomes a far cry for slum residents due to the limited living space per person within their shacks, low hygiene standards and shared community facilities (water taps, common toilets, etc).

Mumbai designated 490 containment zones on April 14 to stop the SARS-CoV-2 spread from these hotspots to other parts of the city. Most zones are within or close to slums such as Dharavi that recorded 800 cases as of May 8.

There are similar incidents of residents unable to follow quarantine rules in overcrowded communities in Ahmedabad and Indore.

These observations suggest density does attract primary virus carriers but its nature and dispersion within a city, in combination with other local factors such as timing and effectiveness of lockdown and demography, may be responsible for the rate of virus transmission.

How do we shape post-pandemic living?

Pandemics with a severity like the present one leave marks on the well-being of every country and their cities. What the final shape of post-pandemic life will be is anybody’s guess.

Every country is grappling with uncertainties and searching for adjustments that will be necessary to endure the present and pave a path for future recovery.

India has, so far, reported fewer deaths compared to many countries, but the lockdown has pushed millions into poverty. Cities, the home of over one-third of the country’s population and the primary source for job creation and innovations, have ceased to function and are losing residents with the on-going exodus of migrant workers.

Emptying out cities is bad news, since size matters for a city’s prosperity. The new normal has shaken confidence and infused fear among people and economic actors.

Local governments are struggling to manage everyday unknowns and fulfil their functions under fast deteriorating fiscal situations. Under these conditions, how a city’s economy can be rebooted and how density can be rebuilt to become safe, healthy, efficient and inclusive becomes one of the primary concerns of local leaders and citizens.

Several city residents have so far managed to gain access to food and are working from home. The pandemic, however, has disproportionately affected poor and marginalised workers. Those leaving cities with fear and lost jobs have failed to meet ends.

In the near future, only a vaccine can fully restore public health and confidence and allow activities and migrants to gradually return. But for sustained progress with resiliency against future infections, priority must be to manage city densities and their form to reduce overcrowded living and prevailing inequalities in accessing affordable housing and essential amenities.

Slums can’t be eliminated in a day. The residents of slums, however, deserve to have sanitised public amenities and services, open spaces and right conditions for their residents to upgrade their quality of life and well-being.

These are old, overlooked issues but they now show us their potential to stall national economy and inflict long-term damage to people’s lives.

During the pre-vaccine phase, state and local governments will be occupied with measures to control virus spread, insure livelihood of unemployed poor and revitalise businesses, supply chains and public transport.

Recovery will be a long-drawn process and largely dependent on how quickly people begin to spend and businesses restore deliveries of goods and services. In China, Korea and Italy, where city economies have just begun to open, progress is marred by low discretionary spending and supply orders.

Under the post-vaccine phase, the government will have the opportunity to sustain and even accelerate some newly-adopted positive trends such as telecommuting, infection risk management, increased biking and walking, physical distancing in crowded places, digitisation of education and routine services, e-commerce and heightened appreciation for clean air and environment.

Many of these new habits are likely to persist if managed well.

Local leaders soon need to address issues of density management and decentralisation of essential amenities and services in communities that are home to migrants, poor and marginalised populations.

The turn-around will require each city’s resolve to manage its densities in the shape it wants using a cohesive team that builds non-traditional partnerships with various local agencies, communities, firms, public and private financiers, experts and relevant non-profits.

Social distancing has ironically drawn people together. It’s an opportune time to engage them in reshaping their cities.

This way perhaps a bottom-up vision for change, its priority actions and investments will be realised and migrants will return to restart a better life and contribute to the economic vibrancy of the country.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

India Environment Portal Resources :

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.