There is no doubt that we will not be able to fix the inequality crisis and build a more equal world without making the rich pay their fair share of tax

The amazingly twittergenic US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposed a 70 per cent marginal tax rate in the United States in January 2019. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders also proposed increased taxation on the richest, focusing on taxing wealth.

These proposals were amplified by the echo chamber at Davos, where we, too, were making similar suggestions in our report, Public Good or Private Wealth. Some billionaires conveniently scoffed and laughed at the proposals which made fantastic copy, culminating in a video featuring the Dutch historian Rutger Bregman and also featuring our very own Winnie Byanyima, being watched 17 million times and counting.

Does this represent a historical shift? Is it some kind of inflexion point? I certainly hope so, but hope is not a strong basis for analysis. In answering this question, it is helpful to look back at the historical experience of taxing the rich.

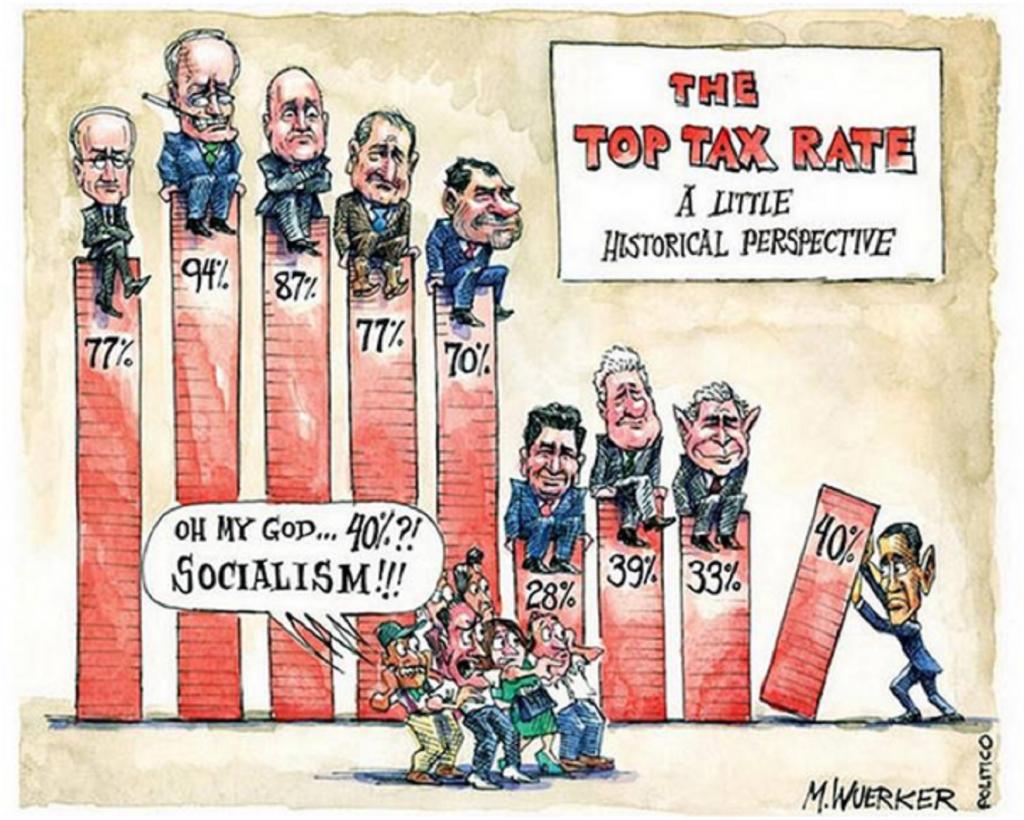

We all know now (except for the billionaire Michael Dell apparently: Watch this clip it is brilliant) that taxes on the rich were far higher in the middle part of the 20th century, especially in the US and UK. But what was the political, social and ideological background to this?

Click here for an interactive version of this chart.

The first thing is the impact of the two World Wars. Income taxes, wealth taxes and inheritance taxes existed before World War I, but they shot up with the advent of war, and then shot up again after World War II. This is not particularly helpful for the campaigners among us, in that it implies we will need another war before we can see a return to progressive tax rates.

Fortunately, there are other factors which are less dramatic and potentially more amenable to purposeful campaigning and change. The US is particularly interesting, because the national debate about the super-rich robber barons of the 1920s and the economic collapse of the Great Depression were very important factors in creating the political space to increase taxes.

Thomas Piketty in his book Capital shows how this was also linked to the fear on part of some influential thinkers in US that they were producing a new aristocracy or ‘plutocracy’; turning into the old Europe that so many of them sought to escape to.

The US pioneered the use of punitive rates of tax on income followed by the UK. Between 1932 and 1980, almost 50 years, the top federal income tax in the US averaged 81 per cent. These very rates of tax were primarily intended not to raise revenue, but instead as a form of sin tax — they were there explicitly to disincentivise paying of extraordinarily high salaries.

Piketty and his colleagues assembled considerable evidence that high rates of tax were enough to discourage highly paid executives in lobbying for higher pay — why put all that effort into pushing for a huge pay packet if 81 per cent is going to the taxman? Certainly, the collapse in top rates of tax has come hand-in-hand with the meteoric expansion in what is paid to those at the top.

The UK led the way on inheritance taxes, with the top rate averaging more than 70 per cent between 1940 and 1980. You can see the evidence if you visit the UK where many former huge aristocratic houses are now museums and open to the public. This was led in part by the strong belief that their upper classes with their inherited wealth had manifestly failed to recognise the dangers of fascism.

In other rich countries, like France and Germany, rates were a lot higher in the 20th century but never as high as the UK or US. Piketty argues that this was in part because these countries were more amenable to managing their economies in the first place to ensure that market inequality is lower, whereas the Anglo-Saxon countries have always been more economically liberal.

In this way, punitive tax rates are a liberal, market-based response to worrying levels of inequality. (Piketty is so good at fresh perspectives like that- I really could not recommend his book more- it is massive, but it is eminently readable, and you can just dip in and read sections without reading it all).

What is clear is that something happened around 1980, and following that top rates of tax collapsed, together with taxes on wealth and taxes on corporates. Not just in the rich countries. In Kenya, as recently as 1988, the top rate of tax was 65 per cent — it is now 30 per cent.

Some point to the power and influence of rich elites over policy making. There is no doubt that this is an important factor. We now have a billionaire in the White House who has given a huge tax cut to the rich.

In the recent budget in Kenya a modest proposal to raise the top rate of tax from 30 to 35 per cent was dropped rapidly, following “concerns from the public”. Our recent study from Latin America shows how the capture of politics has stymied significant numbers of progressive tax reforms.

There is no doubt that strong political support for higher taxes from citizens is needed to counter this capture of politics by elites. But it is not all about political capture.

Elites were almost certainly very powerful and influential during the time of high tax rates in many countries. Rates of inheritance tax and taxation of wealth have collapsed in countries like Sweden too, where democracy is strong and the kind of pollution of politics by organised money we see in the US is largely absent.

For a further explanation we need to look beyond political influence to also look at ideas. Since the 1980s, the view that taxing the richest is counterproductive has become extremely influential. Is this now also beginning to change?

In looking at this, I would distinguish between the views of the typical citizen, and the views of the typically upper middle-class elites that dominate governments, the media and other leadership positions in almost all our countries — and massively dominate the aid industry too, including extremely influential international organisations like the World Bank and IMF.

I don’t think typical citizens ever really bought the idea that much lower taxes on very rich people are in the interest of ordinary people. I think in this case it was more that the strength of opposition to cut taxes for the rich was weakened because there were many other issues to distract — partly because incomes for the majority were improving generally, and partly because much of the cutting was done with very little scrutiny or public awareness, helped in many cases by an elite-dominated media. This has definitely started to shift.

I think for the upper-middle class, managerial elite, it is quite different. Here the majority, I think, really agree with the arguments in favour of not taxing the rich. For them, what was perceived as ‘common sense’ really shifted, putting policies that were only very recently in place firmly beyond the pale.

Perhaps most importantly this happened to the majority of those on the mainstream political left as well as the right, meaning that alternatives were simply not on the table.

Is this changing? Well certainly in bellwether economies like the US and France these issues are very much back in political debate. The protests by the Gilet Jaunes or Yellow vests movement have rocked the French establishment. But French President Emmanuel Macron has so far not reinstated the wealth tax despite giving many other concessions. And Cortez, Sanders and Warren may be brilliant, but they are not in power.

However, they are collectively forcing a shift in terms of the debate, in the understanding of what is common sense. That is crucial, and I think it is really starting to happen. History shows us that the amount of tax the rich pay is primarily a political, societal and moral question.

It is shifts in these areas that will bring change and enable a broadening of the debate and for progressive ideas to be put back on the table. I think it is not unreasonable to think that some of these shifts show signs of happening. The question is: what can we do to accelerate them and ensure they are big enough and permanent enough to underpin real change.

There is no doubt that we will not be able to fix the inequality crisis and build a more equal world without making the rich pay their fair share of tax. It does seem that this view is once again starting to become common sense. Let’s hope so.

Higher minimum wage in Nigeria, fairer wages in Bangladesh

In the video that millions have watched, Byanyima talks powerfully about dignified work and exploitation, and tells the story of poultry workers Oxfam has worked with in the US who have to wear diapers/nappies to work because they cannot have toilet breaks.

On the issue of fairer wages, there was some really positive news this week from Nigeria, where widespread protests organised by trade unions in the run up to the election have led to a really significant increase in the minimum wage.

The government had originally agreed to increase the wage, but then reneged on this promise. It was only in the face of widespread protest that they changed their minds.

At the same time as many as 50,000 garment workers have been striking in Bangladesh for fairer wages. Police killed one protester and as many as 5,000 have been sacked. They are of course almost entirely young women.

I met garment workers at a trade union meeting in Myanmar a few years ago, and it was so inspiring to see ordinary workers fighting back, and taking huge risks to do so. For these young people these ideas of fairer wages and fairer taxes are not old fashioned — they are clearly common sense.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

India Environment Portal Resources :

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.