Compared with the old technology, viewing Day/Night Band imagery is like putting on glasses for the first time

If scientists want to learn more about milky seas, they need to get to one while it’s happening. Trouble is, milky seas are so elusive that it has been almost impossible to sample them. This is where my research comes into play.

Satellites offer a practical way to monitor the vast oceans, but it takes a special instrument able to detect light around 100 million times fainter than daylight. My colleagues and I first explored the potential of satellites in 2004 when we used U.S. defense satellite imagery to confirm a milky sea that a British merchant vessel, the SS Lima, reported in 1995. But the images from these satellites were very noisy, and there was no way we could use them as a search tool.

We had to wait for a better instrument — the Day/Night Band — planned for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s new constellation of satellites. The new sensor went live in late 2011, but our hopes were initially dashed when we realized the Day/Night Band’s high sensitivity also detected light emitted by air molecules. It took years of studying Day/Night Band imagery to be able to interpret what we were seeing.

Finally, on a clear moonless night in early 2018, an odd swoosh-shaped feature appeared in the Day/Night Band imagery offshore Somalia. We compared it with images from the nights before and after. While the clouds and airglow features changed, the swoosh remained. We had found a milky sea! And now we knew how to look for them.

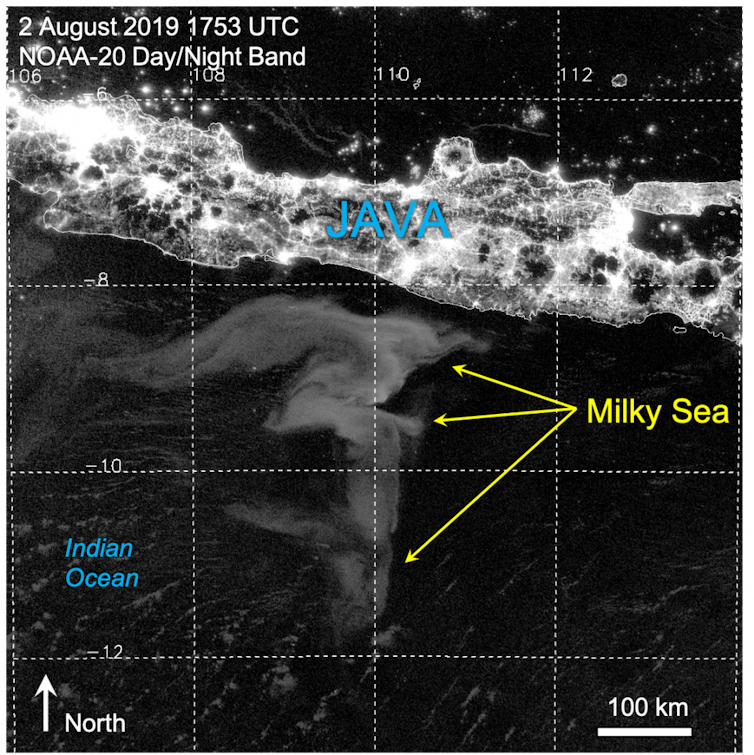

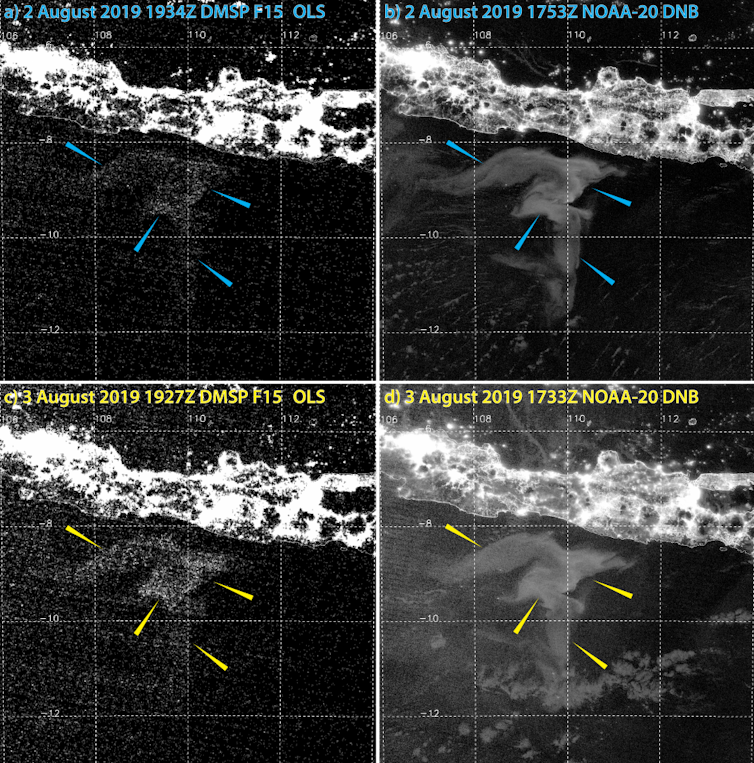

The “aha!” moment that unveiled the full potential of the Day/Night Band came in 2019. I was browsing the imagery looking for clouds masquerading as milky seas when I stumbled upon an astounding event south of the island of Java. I was looking at an enormous swirl of glowing ocean that spanned over 40,000 square miles (100,000 square km) — roughly the size of Kentucky. The imagery from the new sensors provided a level of detail and clarity that I hadn’t imagined possible. I watched in amazement as the glow slowly drifted and morphed with the ocean currents.

We learned a lot from this watershed case: How milky seas are related to sea surface temperature, biomass and the currents — important clues to understanding their formation. As for the estimated number of bacteria involved? Approximately 100 billion trillion cells — nearly the total estimated number of stars in the observable universe!

The future is bright

Compared with the old technology, viewing Day/Night Band imagery is like putting on glasses for the first time. My colleagues and I have analysed thousands of images taken since 2013, and we’ve uncovered 12 milky seas so far. Most happened in the very same waters where mariners have been reporting them for centuries.

Perhaps the most practical revelation is how long a milky sea can last. While some last only a few days, the one near Java carried on for over a month. That means that there is a chance to deploy research craft to these remote events while they are happening. That would allow scientists to measure them in ways that reveal their full composition, how they form, why they’re so rare and what their ecological significance is in nature.

If, like Capt. Kingman, I ever do find myself standing on a ship’s deck, casting a shadow toward the heavens, I’m diving in!

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]![]()

Steven D. Miller, Professor of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.