As the European Union gets set to pronounce whether to give a GI tag to India’s Basmati rice, we explore the history of a grain that transcends human boundaries

Basmati rice. It is the rice fit for kings. But today, these grains of rice are at the centre of a fresh fight between bitter rivals India and Pakistan.

The reason? India applied for an exclusive Geographical Indications tag to Indian-origin basmati rice with the EU’s Council on Quality Schemes for Agricultural and Foodstuffs.

The application was published in an official EU journal on September 11, 2020, after clearing internal evaluations.

In India, basmati cultivation is dictated by geography. There is a ‘Basmati growing region’, one which includes the states and Union territories of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Chandigarh, Delhi, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh.

The cold weather of this region is suitable for Basmati cultivation.

So, what does Pakistan have to do with all this?

Well, apparently, Pakistan too has a Basmati belt, the Kalar bowl, a tract of land in the interfluve between the Ravi and the Chenab rivers, comprising the Narowal, Sialkot, Gujranwala, Hafizabad and Sheikhupura districts in Punjab province.

Turns out that India has a 65 per cent share in the global Basmati market while Pakistan has the rest.

In fact, Pakistan’s exports to the EU have almost doubled over three years since permissible levels of pesticides on imported agricultural products to the bloc were reduced in 2018, while India has repeatedly failed the tests.

Basmati is an export-oriented item for both India and Pakistan

In 2019-20, India produced 7.5 million tonnes of basmati, of which 61 per cent was exported, earning the country Rs 31,025 crore according to the Union Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

According to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the country exported 0.89 million tonnes of basmati in 2019-20.

If India gets the GI tag, Pakistan would be effectively kept out of the European market for basmati rice even though it is a major producer.

History of Basmati

Basmati is most likely of medieval origin. The history and folklore of basmati rice is an academic paper published last year in the Journal of Cereal Research. It was written by Subhash Chander, Uma and Siddharth Ahuja.

Subhash Chander Ahuja is a retired plant pathologist from the Rice Research Station, Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University in Kaul, Haryana. Uma Ahuja is a retired professor of Genetics and Plant Breeding, College of Agriculture, Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University in Kaul, Haryana. Siddharth Ahuja is from the Department of Pharmocology, Shaheed Hasan Khan Mewati Government Medical College, Nalhar, Mewat, Haryana.

In section 3.1 titled Historical growing areas, their paper reads:

The Ain-i-Akbari records cultivation of Mushkeen in the subahs of Lahore, Multan, Allahabad, Oudh, Delhi, Agra, Ajmer and the Raisen area of Malwa Subah

Mushkeen, also called Lal Basmati, is the red-husked variant of Basmati. Though not as popular as the light, golden-husked variant today, the paper says, it was popular in the kitchens of the Mughal Emperors.

Significantly though, the paper reminds us that Basmati did grow in the Lahore and Multan provinces of the Mughal Empire, which are today in present-day Pakistan.

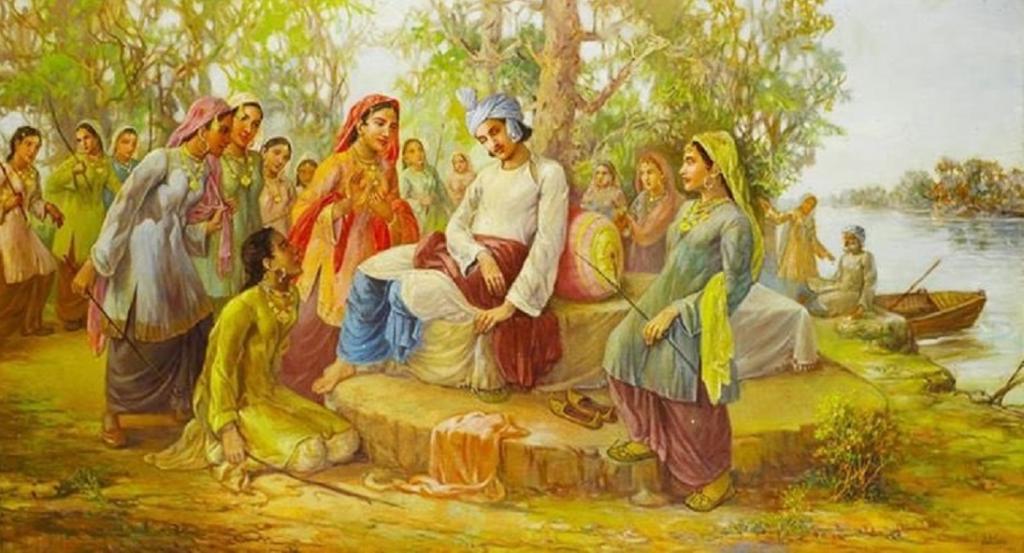

Pakistan’s claim over Basmati is strengthened by the fact that the first mention of the word ‘Basmati’ is in the popular tragic romance, Heer-Ranjha, written in 1766 or 1767 by the Punjabi Sufi, Waris Shah.

The academic paper Range and Limit of Geographical Indication Scheme: The case of Basmati Rice from Punjab Pakistan is by French professor Georges Giraud.

It was published in 2008 in the International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, Volume 11, Issue 1.

It mentions that the romance was translated into English in 1910 by Charles Frederick Usborne, a British Indian Civil Servant and a scholar of Punjabi.

The second paragraph of Chapter 16 of Usborne’s The Adventures of Heer and Ranjha describes several foods displayed for a wedding. It says and I quote:

…All kinds of varieties of rice, even Mushki and Basmutti and Musagir and Begami and Sonputti

It is worth noting that Heer-Ranjha is set in the town of Jhang on the east bank of the Chenab in Pakistan’s Punjab.

Ironically, this paragraph was cited by the Indian government while contesting Texas-based firm, RiceTec’s attempt in the late 1990s to appropriate Basmati rice.

Even more ironically, India at the time was actively supported by the Pakistani government. Both eventually succeeded in thwarting RiceTec’s scheme.

But even as the subcontinental twins squabble over Basmati, Indian farmers are increasingly finding it hard to grow it.

The reasons are many. In just seven years, the price of Basmati has halved. Why? Because, India’s exports have been hit due to the pesticides controversy as well as US sanctions on Iran, a major importer.

Exporters have not paid to rice mill owners, who in turn have reduced purchase of basmati from local cultivators.

This, then, is the current status of our Basmati farmers. Dayanand, a farmer of Basmati from Ghummanhera village on the outskirts of Delhi, told Down To Earth that getting a GI tag from the European Union would not improve his or his peers’ lot.

Returning to the question of the GI tag, India and Pakistan have a bitter relationship. But the Republic of India was founded on the principle of fairness. Morality, fairness and ethics dictate that India is on a sticky wicket as far as claiming Basmati as entirely its own is concerned.

Our move may destroy Pakistan’s basmati farmers. But will it improve the lot of our farmers?

But in these times of hyper-nationalism, populism and nativism, all such talk is anathema, sacrilege and blasphemy. And lest anybody’s sentiments are hurt after seeing this, I tender my apology. As things stand, my task is to inform.

Until the final decision comes out on December 10, on who actually owns it, just sit back…and enjoy your basmati…Bon Appetit.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

India Environment Portal Resources :

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.