The wild pig can be a danger to humans, as some very special ones in northern Iraq found recently

Yesterday, while “leafing” through my Twitter account, I came across this very weird piece of news: Wild boars rampage in Kirkuk leaves 3 Islamic State members dead. At first, I rubbed my eyes in disbelief. Then I read the rest of the copy. Three Islamic State militants died late Sunday when wild boars attacked them in southern Kirkuk, a local source was quoted saying.The animals went on a rampage near a farmland in al-Rashad region, an Islamic State pocket 53 kilometres south of Kirkuk. They attacked the militants and left three killed, according to the source.

The surprises did not stop there. Alsumaria News quoted the source saying that “Daesh (Islamic State) militants took revenge at the pigs that attacked the farmland,” but did not clarify the method.

For most of us in South Asia, the pig usually evinces a variety of emotions, most of them negative. In North India and Pakistan, the most favourite “gaali” (abuse) among men is “Kutta” (dog). Giving that close competition is the pig. So you have words like “suar” and its Urdu counterpart “khanzeer” vying for the top spot with kutta.

Many would argue that the pig deserves all this. It wallows in the muck and worse, indulges in corpophagia (eating faeces). It carries a number of diseases like trichinosis and brucellosis. No wonder then that in two world faiths, Judaism and Islam, the eating of pork is scripturally prohibited. Christianity, the third Abrahamic faith, does allow its adherents to eat swine flesh—most of them except the Seventh Day Adventists, the Ethiopian Orthodox and the Copts.

However, the animal that the domestic pig is descended from—the wild boar has another facet to its story. Here, let me quote from Wikipedia, Jimmy Wales’ brilliant invention that everybody likes to downgrade but turns to at the first instant: The wild boar is a bulky, massively built suid (the porcine family) with short and relatively thin legs. The trunk is short and massive, while the hindquarters are comparatively underdeveloped. The region behind the shoulder blades rises into a hump, and the neck is short and thick, to the point of being nearly immobile. The animal's head is very large, taking up to one third of the body's entire length.

As one can make out from these lines, the wild boar is like a wall of muscle and bone. A tank in the shape of an animal. Consider this: The animal typically attacks (a human) by charging and pointing its tusks towards the intended victim, with most injuries occurring on the thigh region. Once the initial attack is over, the boar steps back, takes position and attacks again if the victim is still moving, only ending once the victim is completely incapacitated.

It is no wonder then that the ancients respected and admired the wild boar and considered him to be a quarry worth fighting. Almost all ancient human cultures in Eurasia (the original home of the wild boar) have folklore about hunting boars and the beasts serve as vexillological symbols—in flags, banners, standards, coat of arms and heraldry.

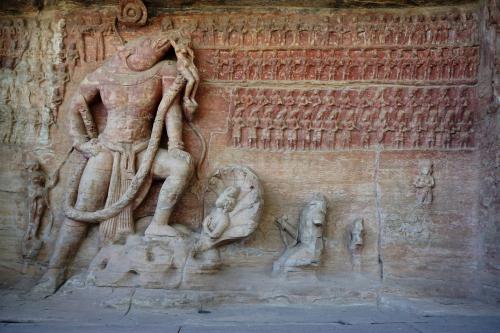

Let us start with our own country. In Hinduism, especially in the branch called Vaishnavism centred on the worship of Vishnu and his avataras, the boar or rather the boar head is part of the body of Varaha, the third avatara of Vishnu. As per legend, he killed the demon Hiranyaksh who had stolen the earth goddess Bhudevi and hidden her in primordial waters. Varaha, after slaying Hiranyaksh, holds Bhudevi, the earth aloft his tusks and bring her back to her rightful place.

It may interest many people to know that until the Turko-Afghan invasions of North India in the 12th century, the wild boar was revered and admired primarily due its association with Varaha. It was a symbol of virility and potency. Testament to this is the number of temples dedicated to Varaha that still exist today across India. The boar was also a royal totem, being the symbol of dynasties including the Guptas and the Gurjara-Pratiharas in the North and the Cholas and Vijayanagar in the South.

Further west, in Europe too, the boar’s association with ancient peoples is legend. Take the ancient Greeks for instance. Almost all their great heroes from Heracles to Odysseus hunt boars to prove their manhood and valour. Some like Adonis even die while trying to hunt a boar. The ancient Romans and the Germanic tribes which succeeded the Roman Empire also hunted boars. Remember the boar helmets from Beowulf?

In Medieval Europe, boar-hunting developed into a fine art. So many boars were hunted that their populations began to decrease. Because of this, by the time of the French Revolution, only the nobility could hunt boars, something that was rescinded once the Revolution took place.

But it is in our own subcontinent that we find one of the finest examples of boar hunting: British India’s tradition of pig-sticking. The whole process was very well-developed: from the horses that officers rode to the spears they used (a specialsed weapon no less) to the dogs (bay and catch dogs) and of course, the quarry—the Indian Wild Boar (Sus scrofa cristatus), a mighty foe. Here is George Archie Stockwell on him from Boars and Boar Hunting:

A boar at bay is by no means a pleasant creature to contemplate, with his huge neck and bristling crest, his fiery eyes, and his glistening, white and champing tusks, rattling like casta nets as they toss off bits of adhesive foam that fleck his brindled sides. It is impossible for those who have never encountered him in his native wilds to realize his fierce and terrible aspect, his lumbering but swift gallop, the bold rush that lifts a horse from the ground,and leaves the imprint of his teeth in its flank as an extended gory rut, or his rage when impaled upon the spear. His last effort is to force himself up the spear-shaft in eagerness to avenge the wound. Little wonder that Orientals accept him as a type of supreme Evil,and condemn his body as the abode of demons and disembodied spirits and Captain Shakespeare, the “East Indian Nimrod,” asserts that no creature aside from, the boar and panther ever made good its charge against his spear or bullets of his heavy rifle!

There, you have it. The awesome power, ferocity, impetuousness and strength of a wild boar. Those who have seen boars fighting tigers, whether the Amur in Ussuriland and Manchuria or the Bengal in India know this first-hand. Obviously, the Daesh fighters did not. And paid for it with their lives.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

India Environment Portal Resources :

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.