At 3 am

Anil Agarwal, founder of Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), and founder editor of Down To Earth, was in Bhopal immediately after the tragedy. This piece captures the state of affairs 15 days into the tragedy An epic tragedy and tales of valour and follies

Ashay Chitre, a filmmaker living in Bhopal’s prestigious Bharat Bhawan, built by the state government to attract artists to this central Indian city, heard a commotion outside his window early in the morning at about 3. It was a chilly December and all the windows of Chitre’s house were closed. As Chitre and his wife Rohini, seven months pregnant, opened the window, they got a whiff of gas. They immediately felt breathless and their eyes and nose began to stream with a yellow fluid. Sensing danger, the couple grabbed a bed sheet and ran out of the house. Unknown to them, all the neighbouring bungalows, which had telephones, had already been evacuated.

Their immediate neighbour, state labour minister Shamsunder Patidar had fled. The chief minister, who lives only 300 m from the Chitres had probably also been informed in time. Outside their house the Chitres found chaos. There was gas everywhere and people were running for their lives in every direction, with nobody to tell them the safe way out. Some fell vomiting and died. The panic was so great that people left their children behind, or did not stop to pick up those overcome by exhaustion or the gas. At one place, the couple saw a family stop running and sit down.

See also: 30 years of Bhopal gas tragedy: A continuing disaster

"We will die together", they said. Another person ran for 15 km in a desperate bid to escape. A passing police van had no clue to the safe direction. Stepping over bodies, the Chitres ran towards the local polytechnic, half-a-kilometre away, where they stopped and decided not to go further. Two hours later, at about 5 am a police van arrived announcing that it was safe to go back home. But nobody believed the policemen.

From the polytechnic, the Chitres rang friends on the other side of the town for help. They returned home three days later. Their pomegranate tree had turned yellow and the peepul tree, black. Three days after that fateful night, Rohini began to experience pain whenever she exercised and Ashay felt his legs buckle. They immediately left for Bombay (Mumbai now) to see a neurologist to ascertain their fate and that of their unborn child.

Mass panic

There were thousands of others that night in Bhopal for whom this macabre drama began much earlier and who were a lot less lucky than the Chitres. Most of them were

the city’s poor, living in the sprawling settlements opposite and around the Union Carbide factory. One of them is Ramnarayan Jadav, a driver of the city corporation,

who says that he had started sensing the gas around 11.30 pm itself. But he stayed on for at least another 45 minutes because “this much gas used to leak every eighth

day and we used to feel irritation in the chest and in the eyes. But finally everything used to calm down.” Even if the company had set off its warning siren then, many

could have escaped.

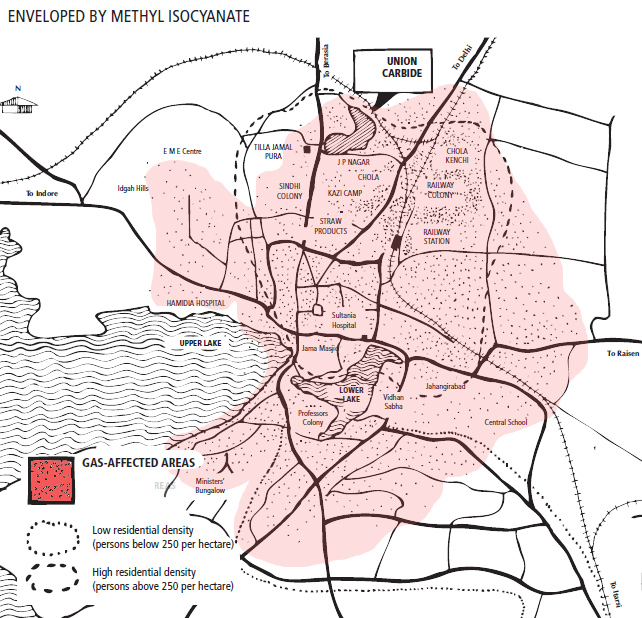

The gas that spewed out of the hi-tech factory of the multinational Union Carbide spread over some 40 sq km and affected people seriously as distant as

five km to eight km downwind. For nearly 200,000 people, a quarter of the city’s population, Bhopal became a gas chamber. If it were not for the two lakes of

Bhopal which came in the way of the gas cloud and neutralised it, an even bigger tragedy could have taken place.

To hospital to die

At Bhopal’s 1,200-bed

Hamidia Hospital, the first patient with eye trouble reported at 1.15 am. Within five minutes, there were a thousand and by 2.30 am there were 4,000, suffering from not

just eye ailments but also from respiratory problems.

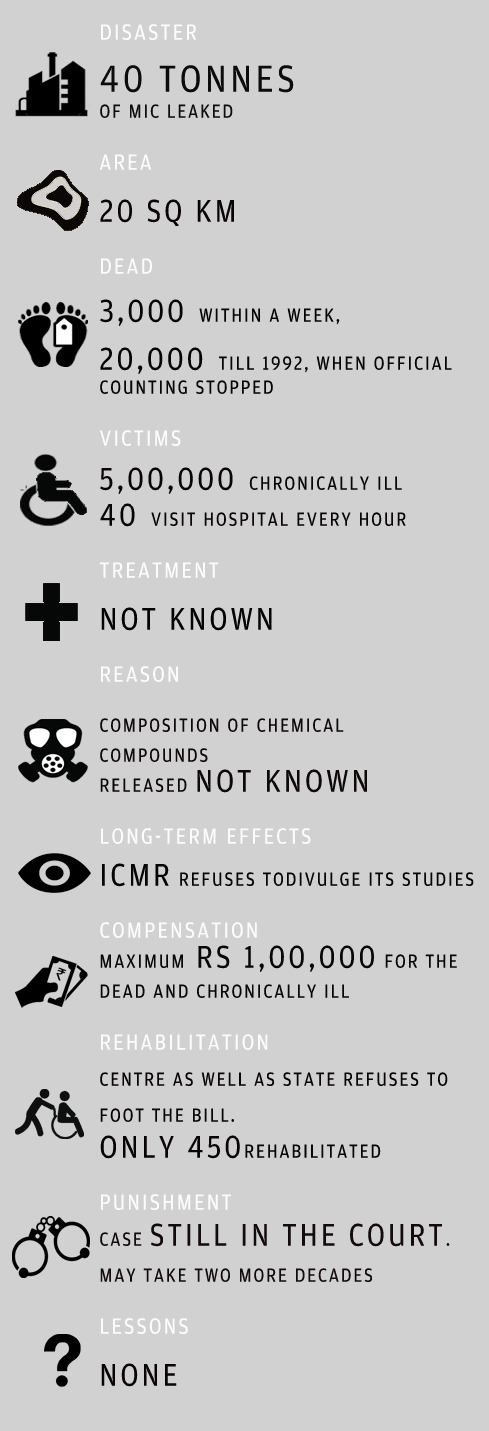

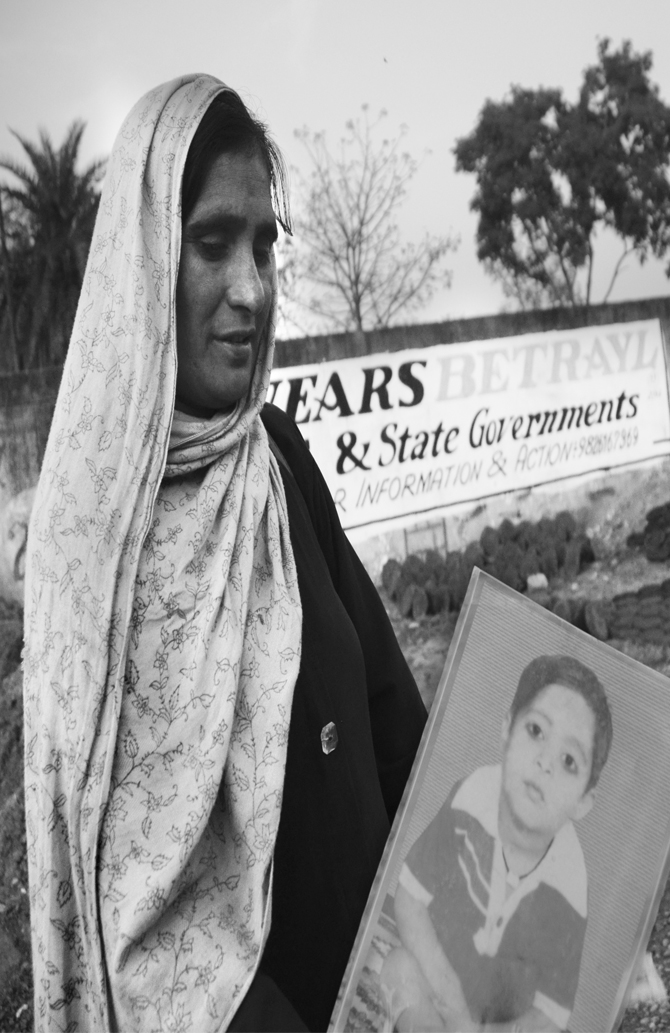

On the intervening night of December 2-3, 1984, methyl isocyanate gas leaking from Union Carbide’s factory in Bhopal claimed more than 5,000 lives. More than half a million people still suffer the side effects of the exposure to the gas; the soil and groundwater have been contaminated and toxicity has crossed over to the second and third generations.

By about 1 am, about 25,000 people were crammed into Hamidia Hospital. The

floor was splattered with blood and vomit. Said a doctor at Hamidia, I saw at least 50 bodies taken away like this. I would

estimate that anything between 500 and 1,000 bodies were taken away before their deaths could be registered.” It was difficult for survivors to identify their dead.

Death drama

At the Hindu cremation ground, about 15 pyres were lit at a time, starting at 9 am. The crematoriums soon ran out of firewood and trucks had to be marshaled to bring in more. To save time, money, energy and humanpower, five to 10 persons were cremated on each pyre. At the Muslim burial ground, too, there was not enough space to bury the bodies coming in. Rescue workers dug graves each holding 11 bodies. The death drama continued for days.

Everywhere one turned, people were retching, racked by violent coughing. All the shops in the city were closed, and on every street people were lying in the gutters. They were dead,

dumped in agonised frozen postures, like birds shot from the sky. In their midst were real birds—vultures. When the vultures swooped away, the

dogs would charge in and tear off pieces of flesh.

A short history of Union Carbide

Union Carbide is the third largest chemical company and 37th largest industrial corporation in the US. It owns 700 chemical

plants, mines, mills and other business operations in 37 countries. Union Carbide’s operations are extremely diverse. It has

been in the nuclear weapons game since the Manhattan Project of World War II, and is the sole contractor manufacturing enriched uranium and weapons components

for the US government.

Union Carbide is the third largest chemical company and 37th largest industrial corporation in the US. It owns 700 chemical

plants, mines, mills and other business operations in 37 countries. Union Carbide’s operations are extremely diverse. It has

been in the nuclear weapons game since the Manhattan Project of World War II, and is the sole contractor manufacturing enriched uranium and weapons components

for the US government.It also makes consumer products like Eveready batteries — it is the world’s largest producer of batteries — industrial gases, and molecular sieves for removing organic chemical pollutants from wastewater streams. Pesticides production is only a relatively small part of Carbide’s operations and not the most profitable one. Sales of agricultural products declined in 1983. Carbamate pesticides, manufactured from methy isocynate (MIC), account for most of Union Carbide’s agricultural products. All of Union Carbide’s operations have the potential of risk to health of workers and communities, and to the environment. When the tragedy at Bhopal happened, Union Carbide tried to picture it as a freak accident that has happened to a company with an otherwise exemplary record in environ mental and health matters. But this was not only untrue, Union Carbide had consistently fought any claims of damages caused by its operations. Vinyl chloride workers, for example, at Union Carbide’s South Charleston plant, were found in 1976 to have not only six cases of angiosarcoma, of the 63 found worldwide

A Union Carbide subsidiary was also responsible for the Gauley Bridge tunnel disaster in the early 1930s, regarded as one of the world’s worst industrial disasters. Construction of the tunnel began in 1930. Gauley Bridge tunnel workers began dying nine to 18 months after exposure to the dust. The company avoided autopsies and death certificates. A US official put the total at 476 dead and 1,500 disabled.

In the 1950s and early ’60s, processes were being developed to use mercury for the separation of lithium-3, a vital component of the hydrogen bomb. One-third or more of the known mercury in the world was bought up for Oak Ridge at this period. A huge quantity of it was lost: £2.4 million was unaccounted for. Some £475,000 was known to have been spilled into a creek. In 1983, Union Carbide’s secrecy cover in Oak Ridge was blown. Mercury at levels 35 times greater than allowed by the state was found in soil.

Union Carbide has also had problems with its major pesticide, Temik. Pure aldicarb is probably the most toxic pesticide manufactured today but it is claimed that it breaks down very rapidly. By 1983, Temik was being used in 38 US states and exported to 60 nations. But events in the early 1980s began to refute the assumption that Temik could not prove a human health hazard because of its rapid breakdown. Temik had been widely used in New York potato fields under Union Carbide assurances that it could not migrate into groundwater. In 1979, about 1,500 wells were found to be contaminated with Temik, at levels above the state’s safe limit for drinking water of seven parts per billion.

Union Carbide has been particularly lax about health and environmental safety in the Third World. It has been operating several plants in Puerto Rico since 1959. Neighbours of at least one of Union Carbide’s operations have been complaining about the ill-effects of air pollution created by the plant. In Yabucoa, Union Carbide manufactures graphite electrodes for the steel industry. Graphite and coke dust, hydrogen sulfide and coal tar gases are emitted into the atmosphere.

In 1981, Union Carbide’s Jakarta factory making Eveready batteries hit the headlines for personnel and worker-health practices that would never be condoned in the US. In 1978, a worker was killed by electrical shock as he stood in water, immersed in a haze of carbon dust, having worked three consecutive days overtime. The new health officer became so distressed with company policy that she resigned in 1979. She found kidney disease and respiratory disorders among workers, excessive heat in working conditions, and mercury in well water supplying drinking water to the workers, and leaching into groundwater under neighbouring rice fields.

Dead administration

It was obvious that the company was pushing hard for the last option. Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) of the US had immediately recommended to its units across the world: use up the remaining MIC to produce carbaryl before governments move in to stop those plants. The local Union Carbide management had reportedly tried to reopen the plant on December 7 itself, just four days after the tragedy, to dispose of the remaining gas. But the staff which reported for duty was turned back by the district administration in control of the plant. Starting the plant again would mean that the chief minister, Arjun Singh, who had piously declared on the fourth day of the disaster that the plant would never be allowed to open again, would have to eat his words. The Times of India pointed out angrily this would amount to a “form of capitulation to the company responsible for the death of over 1,300 persons…It would tantamount to granting Union Carbide some sort of safety approval or certificate and to letting its management, with its all-too-visible safety record, run the plant as it likes.”

.jpg) Word spread on December 10 that the factory had started again, with one district

official claiming that the work to “neutralise the gas had begun” by converting the deadly gas into finished products

Word spread on December 10 that the factory had started again, with one district

official claiming that the work to “neutralise the gas had begun” by converting the deadly gas into finished productsArjun Singh appealed to the people: “There is no cause for panic and I repeat there is no reason to evacuate the city.” But even as the chief minister was saying that, he and his government were acting differently. Government vehicles went around the city announcing to a surprised public that all schools and colleges were being immediately closed for 12 days from the next day.

Zero-risk method

By the next day, the suspense was over. The government had decided to give in to the company. The chief minister announced that the government team had concluded that starting the factory was the “most practical and safe way” among all options for disposal of the gas. This was the “zero-risk” method that he had earlier talked about. He said that the factory would start again from December 16 for four to five days to convert the remaining gas into carbaryl but all safety measures would be adopted and the “neutralisation” process would pose no threat of any kind.

Their worst fears were confirmed when they saw the government’s two minds’ policy continue. The chief minister in the same breath announced that his government was ready to evacuate up to 125,000 people from 13 vulnerable localities to refugee camps, if they wanted to leave, and additional buses would be available for those who wanted to go to friends and relatives in neighbouring towns. A separate camp would also be set up for people’s animals.

Said a Press Trust of India (PTI) report: “The only people left behind (in the 13 localities identified by the chief minister as the sensitive areas) are either those with their own vehicles or those too poor to afford even a ride to safety. The spontaneous migration is unbelievable but true, defying logic or reason. It’s like being driven by the fear of the unknown, a fever spreading like contagion

Matter of faith

The chief minister announced on the evening of December 15: “The scene is set for the operation to neutralise the poisonous gas in the Union Carbide plant. Even though the actual handling is to be done by the Union Carbide people taking full responsibility, the go-ahead has to be given by us—that is me. It is no doubt one of the most crucial and agonising decisions I have been called upon to make. In such moments of supreme loneliness, nothing impels us more than one’s faith in our creator. Even though faith springs eternal in the human heart, at this moment of time it stands rudely shaken by the horrendous events of last few days. That faith has to be restored. This operation shall, therefore, be called Operation Faith. Let us pray for its success.”

At 8.30 am on December 16, the operation started with the much publicised presence of the chief minister, who even took time off to argue with journalists that only 85,000 people had left the city. The governor, K M Chandy, who had earlier refused to drink any water in Bhopal, also visited the plant twice. Outside the factory’s gate, Bharatiya Janata Party president Atal Behari Vajpayee argued with policemen who first denied him permission to enter the plant and then allowed him in. By the end of the first day, four tonnes out of the 15 tonnes estimated to be in storage tank no. 619 and 1.2 tonnes in stainless steel drums, were converted into pesticides., finally ended on Saturday—seven days after it began—and nearly 24 tonnes of the gas had to be converted, over 50 per cent more than earlier estimated. Union Carbide did not even know how much gas it had in store.

Government's response

.jpg) The government’s response was uncertain and tardy—it was to become even so in days to come. The Central government, at the request of the state government, flew in

a team of doctors, followed by a Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) team. The district magistrate ordered closure of the factory on December 3 itself and arrested five

officers of the company in Bhopal. A judicial inquiry into the tragedy was announced. But apart from these routine bureaucratic responses, the state or the

Central government did precious little during the first two days. Except for the army, there was no help coming to the 100,000-odd people who fled from their homes that morning

The government’s response was uncertain and tardy—it was to become even so in days to come. The Central government, at the request of the state government, flew in

a team of doctors, followed by a Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) team. The district magistrate ordered closure of the factory on December 3 itself and arrested five

officers of the company in Bhopal. A judicial inquiry into the tragedy was announced. But apart from these routine bureaucratic responses, the state or the

Central government did precious little during the first two days. Except for the army, there was no help coming to the 100,000-odd people who fled from their homes that morning

The government did not attempt any serious documentation of the extent of injury and new symptoms emerging, and put a gag on doctors to share information with others

The government’s centralisation and lack of initiative, so visible on ordinary days, caused it to literally collapse under stress. Individuals in the administration worked themselves to the wall but there was no overall planning. In those first few hours, there was complete confusion. Once the leak had been confirmed the government apparently decided to evacuate the city. But no one announced this decision to the public at large. The only people who got informed through the government grapevine were the elite: the ministers and those who lived in the colonies far from the plant, and even among those it was mainly people who had telephones. The rest of the people were left to fend for themselves.

Epidemic fears

Three weeks later, there were again fears of outbreaks of epidemics as millions of green flies, attracted by improperly disposed of carcasses invaded the city. The army had initially helped in the removal and disposal of animal carcasses but the authorities admitted that all the animals could not be buried because of a shortage of sanitary workers and scavengers. Most of the municipal staff had been affected by the gas and sanitary workers had to be summoned from other towns. A newspaper report pointed out that on December 4, on his visit to Bhopal, Rajiv Gandhi had declared that the water had been tested and that no toxic substances had been found in it. But Varadarajan later revealed that testing started only on December 5. Not surprisingly, when it came to neutralisation of the remaining gas, the people simply fled the city in unprecedented numbers.

Arrest fiasco

But the manner in which the government handled the arrest of Warren Anderson, the UCC chairperson, was ridiculous. As Anderson landed in Bhopal with UCIL chairperson Keshub Mahindra and managing director V P Gokhale, all three were taken into custody, whisked away in a car with a heavy police escort to the company’s guest house, and lodged in separate rooms from which telephone lines had already been disconnected.

Union Carbide officials, arrested on the first day of the tragedy, were released on bail on the condition that they would help in the neutralisation of the gas left in the plant

They were charged with a series of offences, several of which are non-bailable and punishable with life imprisonment or terms ranging from five to 10 years.

But this bravado, But this bravado, which even brought protests from the White House, ended almost as soon as it began. Within six hours of his arrest Anderson was whisked away from Bhopal in full secrecy, without being produced before a magistrate, as normally required under law, with a paltry bail sum of Rs 20,000, put on a government plane and flown to New Delhi. The embarrassed chief minister who tried to make the best of the situation, said: “What has been done is within the four corners of the law…we wanted him to go in the overall public interest. Not that I feared violence but it could have happened.” But few were impressed by this feat.

Resentment and relief

Almost everybody was coughing constantly, having pain and irritation in the chest. Nobody had turned up to provide these people with medicines or to examine them for the last two to three days. Many of the sick people were not in a position even to get up from their bed. Most of them are daily-wage earners. They were not getting anything to eat. They had no resources to purchase foodgrains. Even if they purchased foodgrains, the women were not physically fit to cook their meals. The moment they sat near the fire, their coughing increased. These people generally belong to an economic class which suffers from malnutrition

Rs 10,000 would be given to the heir of every dead person, Rs 2,000 to those seriously affected and Rs 100 to Rs 1,000 to those slightly affected

The worst record of the government was in the manner it took up relief work. On December 9, the government announced an immediate relief of Rs 100 for ordinary injuries and Rs 2,000 for seriously injured persons.

Newspapers also reported considerable resentment over the distribution of relief money. One gas-affected woman whose eyes had been badly affected wanted to return

the paltry relief money of Rs 200 that she had been given. Financial assistance was handed over in crossed cheques. To cash these cheques, the victims had to first get

them identified and open an account in the banks after depositing Rs 20. The banks had to seek special permission to open accounts for those poor families who did not even

have the initial deposit of Rs 20.

Newspapers also reported considerable resentment over the distribution of relief money. One gas-affected woman whose eyes had been badly affected wanted to return

the paltry relief money of Rs 200 that she had been given. Financial assistance was handed over in crossed cheques. To cash these cheques, the victims had to first get

them identified and open an account in the banks after depositing Rs 20. The banks had to seek special permission to open accounts for those poor families who did not even

have the initial deposit of Rs 20.Long Wait

In a desperate bid to get themselves cured, people sat in long queues before mobile clinics, dispensaries and polyclinics set up by the government, and a dozen other dispensaries set up by voluntary agencies. At these centres, they got the same treatment, antibiotics and a few other drugs, which after a while began to create more side-effects than benefits. Those unable to bear their health problems tried to seek the assistance of the big hospitals but from there they were invariably turned back. Others simply lay at home in bed. But with the government and the medical community in Bhopal arguing in less than a fortnight that the worst was over—that most of the problems people were now complaining about were mainly the result of common diseases like anaemia and TB rampant in these slums—the people found themselves caught between a callous multinational and a highly inefficient and equally callous government.

The government itself did not attempt any serious documentation of the extent of injury and new symptoms emerging. No effort was made to take X-ray, collect and analyse blood, sputum or urine samples and keep people under observation. Even worse, the entire affair was shrouded in total secrecy. Even as people complained of various ailments, the government tried to suppress all information. According to one report, the dean of the Gandhi Medical College in Bhopal even called a meeting of representatives of private medical practitioners in mid-January to demand that they disclose no facts pertaining to MIC poisoning to anyone but the state government.

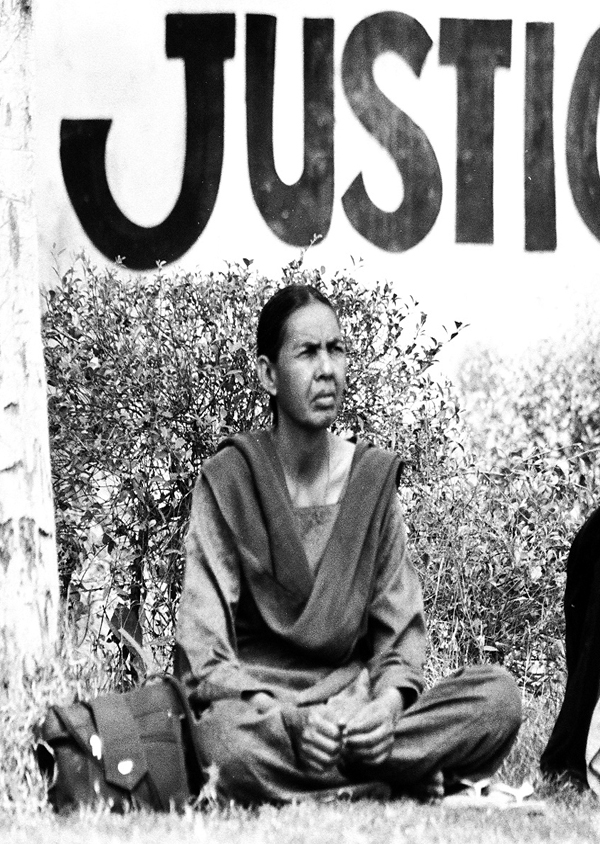

Public protest

By early January, the mood turned angry and resentful. On January 1, Nagrik Rahat aur Punarwas Samiti organised a chakkajam (stop the wheels) programme by squatting on the main thoroughfare of the city. On January 3, the Zahareeli Gas Kand Sangharsh Morcha, a forum organised by scientists, social activists and trade union workers, observed a Dhikkar Diwas (day of condemnation) and a dharna (protest) in front of the chief minister’s house. The daylong dharna turned into a 10-day-long affair and finally got converted into a rail roko (stop the trains) programme.

The single biggest ground for resentment was the delayed distribution of ex gratia payments by the government, which had announced that Rs 10,000 would be given to the heir of every dead person, Rs 2,000 to those seriously affected and Rs 100 to Rs 1,000 to those slightly affected. In its initial panic, the government had rushed payments and Rs 36.67 lakh was paid in cash to 5,724 victims. But on December 7, the government suspended the disbursement and announced that it would be resumed later—and payment would be by cheque—only after a quick house-to-house survey of the affected localities.

The Bhopal tragedy has amply shown that it would be futile to expect the government to deal with such emergencies with any measure of efficiency. And yet high-risk industria lisation has made this an imperative.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

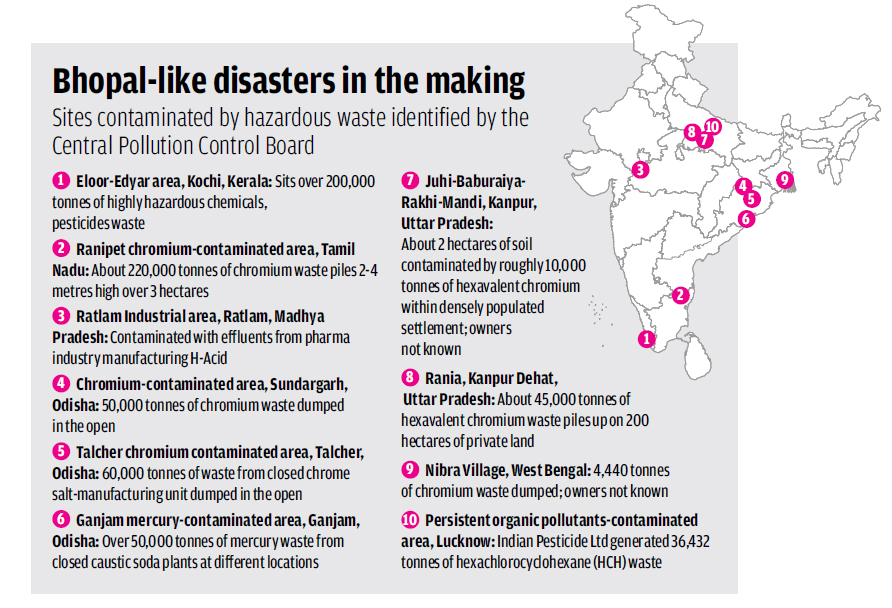

In 2010, the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) launched a project for remediation of sites contaminated by hazardous waste with much fanfare. A total of 10 toxic sites were identified.

In 2010, the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) launched a project for remediation of sites contaminated by hazardous waste with much fanfare. A total of 10 toxic sites were identified.