What makes animals stray into human habitations? With the Centre permitting states to cull animals declared as vermin, we explore some of the reasons behind the trend

Monkeys, along with Grey langurs and bonnet macaques, have adapted to urban habitats over the years, says Goutam Sharma, a faculty member with the animal behaviour unit under the department of zoology, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur. “Out of the nearly 225 living species of non-human primates, these three species have adapted to the urban way of life,” he says.

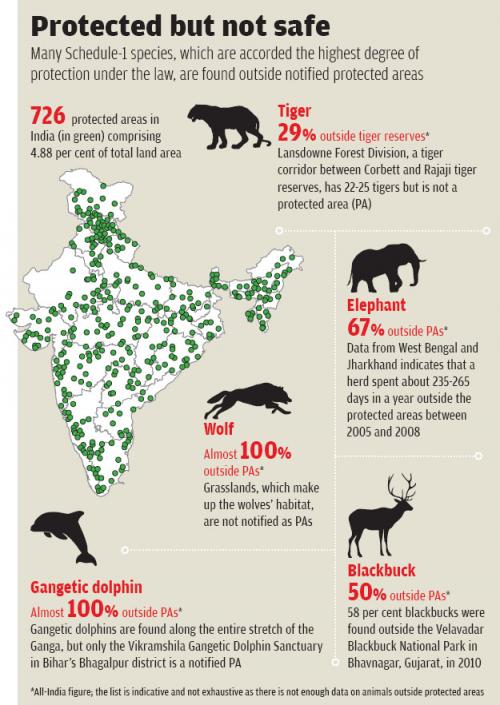

In case of other animals, India does not lack protected areas, but the very idea of a protected area appears skewed. “The protected areas were historically meant to be the breeding grounds for animals raised in the wild for the purpose of hunting,” says S S Bist, emeritus scientist at Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun. This space is not enough to have a full-fledged habitat for wild animals, he adds.

A former official of the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) explains with an example. “A territorial animal like a male tiger needs an area of 60-100 sq km. But the area allocated to an entire tiger reserve, like the Bor Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra, is 138.12 sq km. This is barely enough for one or two tigers,” he says.

Bist underlines a similar case for elephants. “The elephants need to travel at least 10-20 km a day. If a herd is restricted to an area of about 100 sq km, they are bound to move out in search of food and water. Elephants are used to travelling long distances, most of which fall outside the protected areas,” he says.

The condition of the existing protected areas is not very good, either. Wildlife experts claim that territorial animals do not have enough space within reserves and their prey do not have enough fodder to thrive on. This is forcing the wild animals to move out and venture close to human habitation in search of food.

The population of monkeys has multiplied after their natural habitat was destroyed because of their ability to adapt to new habitats. “In forests, a Rhesus macaque has to spend about 10 to 14 hours in search of food. However, if we look at the street-dwelling urban monkeys or even those living dangerously close to human settlements in a rural setting, finding food takes only 10 minutes,” says Satish Sood, who heads one of the state-run sterilisation centres for monkeys in Himachal Pradesh. “When there is food in abundance, monkeys spend more time procreating,” he says.

A primary reason for the increasing human-animal conflicts is the presence of a large number of animals and birds outside the notified protected areas. Wildlife experts estimate that 29 per cent of the tigers in India are outside the protected areas. “If we take their number to be 2,200, the tigers outside the protected areas are about 640. This is almost twice the number of tigers found in Russia,” says a senior conservationist at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun.

Another reason why animals move to new geographical areas is the government’s practice of translocating monkeys from the cities to forest areas near rural areas. Residents of Chaukha village, which is at an altitude of 2,072 metres above sea level, say monkeys were brought to the forests from Shimla and Mandi. “Monkeys are never found at such high altitudes. But the government forcefully dumped the animals in our forests,” says Verma.

Even Delhi’s attempt to translocate monkeys has backfired. In 2007, the state wildlife department captured over 19,000 monkeys to translocate them to a wildlife sanctuary created at Asola Bhatti mines on the outskirts of the city. While New Delhi breathed a temporary sigh of relief by the move, the residents of Sanjay Colony near the sanctuary struggled. The illegal colony of the Od community, who for three decades mined Bhatti area of the Aravalli hills, registered an alarmingly high number of attacks by monkeys who would escape the sanctuary.

State governments have tried various strategies so far—from culling and sterilisation drives to awareness campaigns not to feed monkeys. In Himachal Pradesh, the sterilisation rate at the centres has been poor. On an average, each camp has the capacity to sterilise 45 monkeys every day. This adds up to 54,000 sterilisations every year or 430,000 sterilisations in the past eight years. But just 96,500 monkeys have been sterilised since 2007.

Wildlife experts warn that if wildlife protection is confined to reserves and parks alone, several species will stand at the brink of extinction. This is best exemplified by the Great Indian Bustard, which is a Schedule-I animal. Despite having sanctuaries to itself, the bird has been driven to the brink of extinction. “Various bustard sanctuaries had sizeable population once upon a time. But as of March 2015, there are an estimated 169 birds left. The problem is how do you restrict a bird? They fly out of the protected areas and are then hunted for their meat,” says Sutirtha Dutta, a researcher at WII.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

India Environment Portal Resources :

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.