For Africa, solid waste management is becoming a major concern. The writer reports from Zanzibar and Swaziland on how two contrasting scenarios are offering solutions

Africa has been undergoing the fastest rate of urbanisation for the past two decades at 3.5 per cent a year, suggests the African Development Bank Group (AFDB). About 36 per cent people in the continent now live in urban areas, a share that is expected to reach 50 per cent by 2050, according to the World Bank. A fallout of this is the enormous amount of solid waste. What’s worse, the bulk of the urban population stays in slums where “waste management services are often woefully inadequate”, according to a 2014 UN Habitat note, titled Urbanisation Challenges, Waste Management, and Development.

The island state of Zanzibar, a semi autonomous part of Tanzania with a population of 1.3 million or just 12 per cent of Delhi’s population, is a classic example of the challenges associated with rapid urbanisation in the continent. It has no official strategy on solid or biomedical waste management. About half of the waste generated in the capital city of Zanzibar Town is either burnt locally or dumped in the neighbourhood. The rest reaches the lone landfill serving the city, the Kibele landfill site. But this site, set up in 2011 with the help of the World Bank, is also plagued with problems. It is just a kilometre away from settlements and falls in the buffer zone of the Kibele forest. “Communities often complain about the open burning of waste,” says Aboud Jumbe, officer, Department of Environment. The World Bank invested US $33 million between 2011 and 2016 to develop the area into a modern sanitary landfill site. It is still used only as a dumping site. As a result, the World Bank has decided to extend the funding for three years. “Another $55 million will be sanctioned for the next three years to develop a sanitary landfill site,” says Makame Machano Haji from the Zanzibar Urban Services Project, Ministry of Finance.

The country is also struggling with its biomedical waste. It has an injection safety and waste management protocol, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the US, but has no guidelines on biomedical waste. The lack of mandatory waste segregation and the burning of mixed waste means hospitals are emitting two highly carcinogenic pollutants, dioxin and furan, into the air. The country has eight major hospitals and several small clinics. Mnazi Mmoja, the largest hospital in Zanzibar, generates 500-1,000 kg of hospital waste a day. The waste, which includes injection vials, syringes, saline bottles, catheters, blood bags and needles, is burnt in the hospital backyard. The liquid effluent, including sewage, urine, blood and other infected body fluids, is drained into the sea, risking the marine biodiversity of the island. “We have little information on how the clinics handle their waste,” says Jumbe.

Poor biomedical waste management practices have encouraged the illegal market of used syringes that has increased the spread of infections such as Hepatitis B and HIV/AIDS, says a senior Mnazi Mmoja official on the condition of anonymity.

Zanzibar Town has 86 designated waste-dumping points. It has another 92 illegal waste-dumping points, with no collection system in place. The collection efficiency in Stone Town, a UNESCO world heritage site of a Swahili trading town that is spread over 35 ha in the capital city, is 86 per cent. The collection efficiency in the rest of the city is less than 40 per cent. “Only Stone Town has the facility of door-to-door collection,” says Mzee Khemis Jume, sanitation engineer, Zanzibar Municipal Council (ZMC).

Bad for tourism

Waste mismanagement is impacting tourism, which accounts for 40 per cent of Zanzibar’s economy. “Many tourists from developed countries complain about the garbage and stench on the beaches,” says Julia Bishop, vice-chairperson, Zanzibar Association of Tourism Investors. She adds that the country needs to move towards eco-tourism, otherwise the progress of the island will halt. Every year, 0.5-0.6 million tourists visit Zanzibar.

“One of the biggest problems is the lack of garbage collection. If garbage is not collected daily, it will dissuade foreign tourists,” says Alok Gupta, manager, Hotel Maru Maru in Stone Town. ZMC charges every household 2,000 Tanzania Shilling or Ts ($1 equals 2,200 Ts) per month for collecting solid waste. But just 43 per cent of the households pay this fee. Commercial establishments pay 6,500 to 350,000 Ts per month for garbage collection.

The island state is working on a National Strategy for Waste Management and developing Environment Impact Assessment guidelines for hotels, says Farhat Mbourak from the Zanzibar Environment Management Authority. It has also allowed private players to collect waste. Zanrec is one such company that collects and recycles waste, mainly from hotels and communities in north, central and south Zanzibar with the support of the local government and communities. “We started in 2011 and today have 42 employees who collect segregated waste from 44 hotels,” says Shabbir Adamali, general manager, Zanrec. They compost the wet waste and sell the dry waste to recycling companies. Plastic, metal and glass waste is sold to recycling companies in India, China and Germany. The inert waste goes to the Kibele landfill site. The company also awards certificates to hotels which follow its waste management guidelines. Zanrec charges $18 a month per hotel room and serves the communities for free. The company, which is currently collecting waste from 900 hotel rooms, says it is making losses. “We need at least 1,600 rooms to break even,” says Adamali.

A culture of reuse

While Zanzibar is struggling, Swaziland, one of the smallest countries in the world with a comparable population, is promoting its inherent culture of recycling waste products. Seeds, flowers, plants, paper, plastic as well as glass waste are reused or upcycled into new products in Swaziland. Even local urban bodies have installed grand displays made of upcycled products such as abandoned vehicles, tyres and e-waste to promote reuse and spread awareness across the country.

The culture of recycling waste can be best seen in Swaziland’s handicraft industry that has flourished through cooperatives. “It started with a handful of companies, all with a similar social mission to empower communities. They first founded the Pure Swazi, and later the Swaziland Fair Trade (SWIFT). Since its inception in 2010, SWIFT has pushed the industry to new heights and supported new companies,” says Sibusiso C Msibi, Swaziland Environment Authority (SEA).

Recycling glass

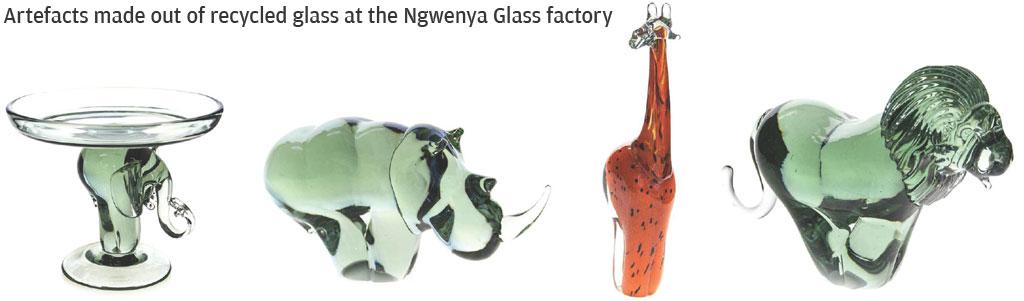

In 1987, Ngwenya Glass started making glassware—using only recycled glass, mainly old cold drink bottles. “Each and every piece is handmade using the glassblowing method,” says Armstrong Nsibandze of SEA. Ngwenya Glass works with local schools and colleges to instill in the children a sense of environmental awareness. And people from all over Swaziland collect bottles to sell it to the company. “Ngwenya must be the cleanest area because any bottle that catches the children’s attention finds its way into the factory,” says Nsibandze.

The company, started by Swedish Aid, has survived because of Sibusiso Mhlanga, the company’s production manager, who introduced the Swedish glassblowing technique in the region in 1979. “I spent nine months in Sweden, training at the world famous Kosta Boda glassworks under Jan Erik Ritzman,” says Mhlanga. On returning to Swaziland, he joined the company, which was shut down in 1985, but reopened in 1987. Mhlanga has since trained the entire workforce of 70 people. It is the only glass-blowing factory in Africa and among a select few in the world.

“Close to 0.5 tonnes of glass is collected per day from communities at the rate of 1 rand per kg ($1 equals 13 rands) of glass deposited at the collection centre,” says Mhlanga. The glass pieces are washed to remove paper and mud. They are then crushed and fed into the furnace. “To see a blob of glass turning into colourful art in front of your eyes is inspiring,” says Mhlanga.

Advantage women

Another initiative that is using waste is Gone Rural, which was founded to empower women in the remote areas of Swaziland in 1992. Jenny Thorne, the founder of the initiative, started a small craft shop in a mud hut in the 1970s. As the business grew, Thorne decided to focus on hand-woven products and turned to the indigenous Lutindzi grass, which has a natural waxy finish, making it water- and stain-resistant. It is working with over 770 artisans in 53 communities across the country. The initiative promotes upcycling of plastic and magazine paper by making jewellery pieces and artefacts out of waste. “Besides promoting a culture of reuse, it is helping the women of Swaziland to become financially independent. It also educates women about HIV/AIDS, which is a major problem in Swaziland,” says Banele Nyamane, an art collector in Swaziland.

While the Swaziland examples are encouraging and have been able to make changes at the community level, recycling handicrafts alone will not be enough. According to AFDB, Africa will continue to be the fastest urbanising continent till 2050 and its urban population will almost double by 2060. So countries need to immediately develop comprehensive waste management practices and ensure their effective implementation. Till then, the urban waste situation will only worsen.

The story has been taken from the 1-15 March, 2017 issue of Down To Earth magazine

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

India Environment Portal Resources :

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.