The habitability of housing, rather than just its availability, will be an important factor in the future, given the trends in climate change

The summer of 2022 has been the second-hottest since 2010, according to Delhi-based think tank, Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). The winter, monsoon and post-monsoon are also warming up. The mere availability of housing is no longer sufficient in such a scenario. It should also be ‘habitable’.

Regular heatwaves in previous years have led to abnormal and uncomfortably high daytime night-time temperatures, especially in cities. This happens due to the inability of an urban area to cool down after sunset as it gets flooded with heat exhaust from thousands of air conditioners.

Read Why innovative cool roofing is becoming popular among Ahmedabad’s urban poor

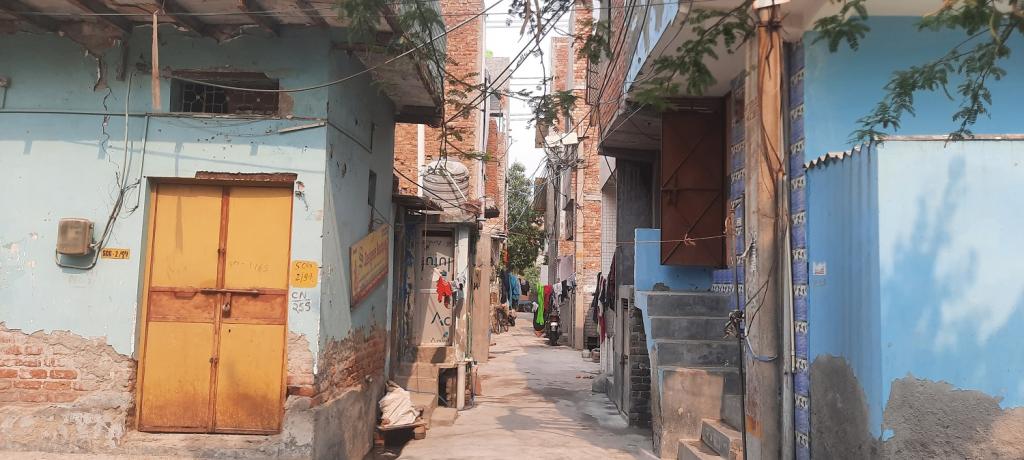

The stress of climate change is even worse in the case of housing which is congested. No access to ventilation in the house adds up to the adversity.

The same housing space is used for different functions and is shared between multiple members. The unavailability of cooling options and material quality of the housing unit (for example asbestos roofs) further make the occupants more vulnerable.

This also directly affects the productivity and health of the household members. Improvising housing conditions also becomes difficult due to the limited availability of capital and resource.

The occupants of such housing are usually the urban poor. Chandni Singh, senior researcher at Indian Institute for Human Settlements and a lead author at Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, had told the BBC this summer: “Poor people have fewer resources to cool down as well as fewer options to stay inside, away from the heat.”

The scope of the human right to adequate housing is guaranteed by Article 11.1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

It was elaborated by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in its General Comment 4 on ‘The right to adequate housing.’

The Committee established that in order for housing to be adequate, it must, at a minimum, include seven core elements. These are legal security of tenure, availability of services, affordability, habitability, accessibility, location and cultural adequacy.

Some 32.2 per cent of Delhi’s population (including both rural and urban) stays in single-room dwellings, according to the Delhi Statistical Handbook 2013. They are followed by 29.6 per cent of those staying in homes with two rooms.

Since 1990, Delhi has witnessed an urban restructuring through forced eviction and peripheral resettlement of homes and families. After the Emergency, these past few decades have seen the largest rise in such forced evictions.

Ayona Dutta, then a senior lecturer in the School of Geography, University of Leeds, had noted in 2013:

With the law on their side, politicians, middle-classes, business investors, and multinational corporations have been largely successful in removing the urban poor from the ‘legal’ city.

Narela and Bawana have turned into holding areas for Delhi’s ‘illegal’ residents who were approved for legal housing as long as they left the city.

‘Eligible’ squatters in Delhi used to receive a 25 square metre plot of land with a freehold title in the 1970s and 1980s. They now receive only a 12.5 square metre allotment with a 10-year lease that they cannot sell or pass on to their descendants.

Families have got a parcel of land measuring 12 or 18 square metres on lease in resettlement colonies like Savda Ghewra, Madanpur Khadar and Prayog Vihar, among other places.

The size of the plot remains independent of the size of the household. This further increases the congestion.

Sudha, a resident of Madanpur Khadar, lives in a single-room house with her two children and husband. She is a domestic worker and her husband works as a loading and unloading worker.

They shifted into their current house in 1999, after the demolition of their basti (slum) in Yamuna Pusht. They were allocated a plot of size 12 square metres over which they incrementally built their house.

Currently, the house has one room with a toilet built outside. Inside the room, there is a family’s double bed, a kitchen slab in one corner and a washing machine tightly fitted between the two.

The house has two openings. One is a door and the other is a small opening above it.

Sudha is particular about her cooking timings in the afternoon as cooking traps heat in the house which finds no way to escape. She mentioned how cooking during peak afternoon increased the temperature of the room, after which sitting in it was extremely uncomfortable.

Hence, deciding hours for cooking and adjusting timings for her work is crucial. During her regular work days, she prefers to cook lunch and breakfast at the same time in the morning before leaving for work.

The same room is used by the members in different capacities at different times: For sleeping, watching TV (tucked on one of the four walls), cooking, studying and others.

Building houses with independent kitchens and multiple rooms is not possible in these resettlement plots provided by the state. Also, the state doesn’t provide any financial incentives to people for building their houses.

Incrementally building the housing unit seems to be the only way of moving forward, according to Raghav, a resident of Sawda Ghewra.

“When we first came here, there was nothing. The government’s bus just left us here on the outskirts. No transport, no water. There was only electricity. We first built the house with bamboo and tarpaulin, later with asbestos and now it is pucca, as you can see,” he said.

Currently, many households have successfully built two to three floors in Sawda with an increase in income over time.

But incremental development of housing takes time, which leaves the population to adjust to the limited space and services. Securing land titles and basic structure becomes more important for the citizens than emphasising the habitability of the space.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.