Kenyan authorities are caught between reviving a dying lake and ensuring livelihood to farmers living in its catchment

For three decades, James Wainana has grown maize and vegetables along Ol’ Bolossat—the only lake in the fertile Central High-lands of Kenya. But today he is no longer sure of investing in his four-hectare (ha) farmland. Like him, more than 0.56 million farmers, who live in the catchment area of the lake, are anxious because of a plan to conserve the lake.

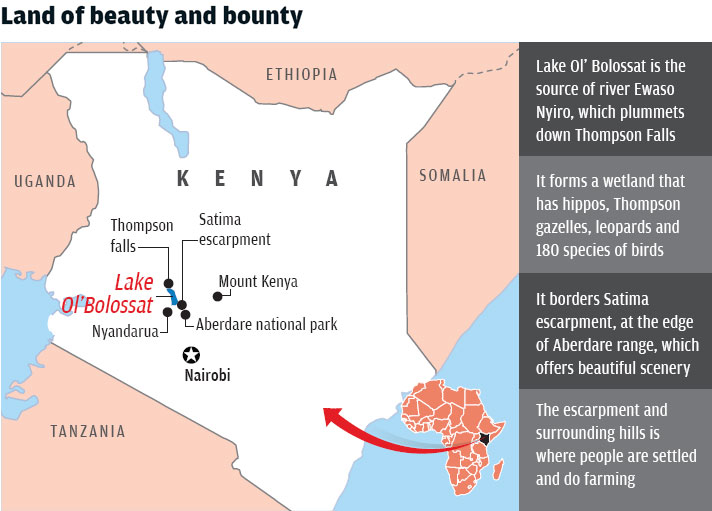

In June 2014, Waithaka Mwangi, governor of the Nyandarua County, announced the lake will be developed as a tourist destination. The revenue earned from tourism would be spent to revive the lake, which is a habitat for hippopotamus and many birds, and the source of river Ewaso Nyiro, the third longest in Kenya (see ‘Land of beauty and bounty’). The government believes Ol’ Bolossat has degraded due to a sharp increase in human population and unchecked farming—Nyandarua is known as the bread basket of Kenya. Farmers divert water from streams and springs flowing into the lake to irrigate crops. Continued tilling of land is silting the lake, while pesticides are polluting the water. Farmers’ livestock also compete for pastures with hippos.

The tourism project requires the county government to acquire farmland and plots encroaching upon the catchment and riparian areas of the lake, which is protected under the Water Act, 2002. But the authorities are not sure which plots to acquire and how to resettle the farmers. This is because the 43-km-long lake is yet to be gazzetted; meaning, it does not exist in government records and its boundaries and the catchment areas are yet to be marked.

Besides, the county government has no powers to acquire the land, says Gitau Thabanja, county executive in charge of land, housing and physical planning. “We are also not sure what to do with the communities occupying the catchment and riparian land,” says Thabanja. He adds that the government has sought the advice of the National Lands Commission (NLC) in this regard.

NLC is a constitutionally sanctioned independent body that manages public land on behalf of the national government. In September last year, its chairperson Muhammad Swazuri led a fact-finding mission to the area to assess the situation. NLC was formed just four years ago and is not aware of how the farmers were settled in the lake’s catchment and riparian areas, says Abigal Mukolwe, vice-chairperson of NLC.

Slips of the past

The land in lake’s ecosystem was initially occupied by European settlers, who grew wheat and other crops on a large scale. After Kenya attained independence in 1963, the government allocated small tracts of land—1 to 4 ha—to farmers with small landholdings through settlement schemes. Later in 1983, the government again settled more people in the buffer zone demarcated between the lake and the settled areas. It was close to the high water mark level. In the absence of a national authority to monitor activities near the lake, illegal structures mushroomed in its catchment. Today, many schools and shopping centres can be seen in the area.

Need of the hour

Seven years ago, Kenya’s environmental watchdog National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) had warned that inaction to protect the lake can cause irreparable damage. The lake had dried up in 1960 and 1984, when Kenya experienced its worst droughts, but it still came back to life. NEMA said if the lake dries up again, it may never reappear, given the ever increasing human activities in its basin. The conservation of the lake necessitates that farmers living in its catchment surrender their land. But the government should ensure they are resettled and adequately compensated, says Lillian Muchungi, who works with Green Belt Movement, a conservation non-profit.

One such way could be to involve the community in conservation projects. For instance, Olobolosat Conservancy, a conservation non-profit, asked Laikipia county government to provide land to set up a hippo sanctuary near Manguo swamp, 10 km from the lake.

George Muchina, the Chief Executive Officer of the Conservancy, says the project can employ people from the community and can also mitigate the human-hippo conflict. The farmers also prefer to stay and earn livelihood from tourism and conservation. “No one would be happy to be moved out of his land. This is where some of us have lived for years and not all of us were allocated land illegally,” says Wainana.

The article has been published in the September 16-30 issue of Down To Earth magazine.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.