There are prominent shortcomings in implementation, especially registration of workers and and collection and distribution of Cess

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic had widespread and devastating consequences to communities and enterprises in India and across the globe. However, the situation was particularly grim for the 453.6 million internal migrants in India, evidenced by the unprecedented ‘reverse migration’ witnessed during the pandemic.

Their vulnerabilities were exacerbated by the fact a large section of the working-age migrant population in India finds employment in the informal economy, which denied them any access to social security benefits upon stoppage of work due to lockdown.

The spatial distribution of economic growth and prosperity in India in the past two-and-a-half decades has been agglomerated in-and-around pre-existing centres of growth. This has accentuated the pre-existing disparities in terms of economic growth, prosperity and livelihood opportunities between the cities and the resource-poor regions of this country.

As a result, the country has seen a stupendous rise of the construction industry, particularly in the major metropolitan centres. The contribution of the construction sector to the real growth rate of the gross value added at basic prices reached 6.8 per cent during 2016-2019.

Construction, which was one of the worst-hit sectors during the pandemic, is also one of the key sectors in which India’s migrant workforce find employment. The NSSO (2016-17) puts the number of construction workers in the country at over 74 million.

Interstate migrant workers make 35.4 per cent of all the construction workers in the country’s urban areas, according to the 2001 Census. Of all the interstate migrants in India who move out of the farm sector, construction absorbs around 9.8 per cent, making it the second most preferred sector for migrant workers after retail.

Furthermore, 26 per cent of all households with migrant workers employed in the construction sector have a minimum of three members with at least two working adults of different genders, indicative of nuclear families with children, who can be viewed as associational migrants in construction.

The Jan Sahas Survey conducted at the beginning of the lockdown (March 27-29, 2020), found that 54 per cent of construction workers support three to five people, while 32 per cent support more than five people.

Legal safeguards

The Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act and the Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Cess Act were constituted in 1996, to address the issues faced by the construction workers.

These legislatures mandated the institution of a Construction Workers Welfare Board (CWWB) — a tripartite entity with equal representation from workers, employers and the government. The CWWB is required to register all construction workers in the state and promote the welfare of registered construction workers through various schemes, measures or facilities.

Indicative welfare benefits are listed out in Section 22 of the Act and include medical assistance, maternity benefits, accident cover, pension, educational assistance for children of workers, assistance to family members in case of death, group insurance, loans, funeral assistance and marriage assistance for children of workers.

For the purpose of raising capital for providing the welfare benefits under state CWWBs, collection of a cess at the rate of 1 per cent of the total cost of construction is mandated by the said legislations.

Shortcomings in implementation

There are some prominent shortcomings in implementation, especially with regards to registration of workers and the collection and distribution of the Cess. The number of active / valid registrations vis-a-vis the total number of construction workers registered in the state CWWBs, is a major issue.

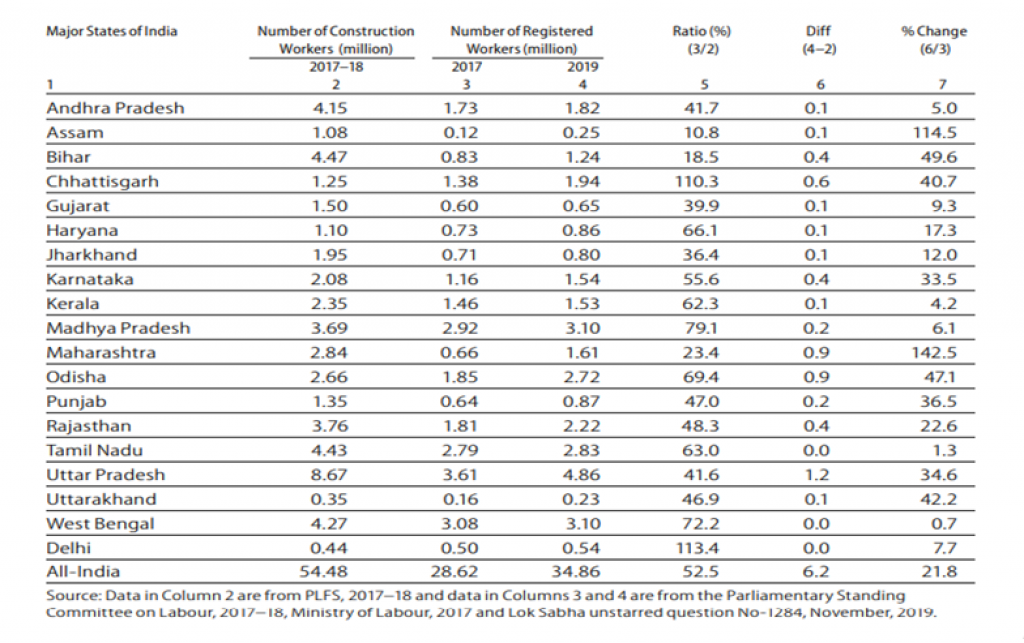

State-wise number of construction & registered workers

The state-wise scenario of construction workers from 2017-2019 can be seen above. It shows that there are approximately 55 million construction workers and based on the estimation, there would be about 20 million construction workers who would be unable to avail the benefits given out by the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) mode.

This can be attributed to the fact that the registration rates are not very high, the estimates show that only 52.5 per cent of all construction workers were registered in 2017. Rates of registration are extremely low in Assam and Bihar (< 20 per cent); in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh, it is lower than the national average.

However, states like Delhi and Chhattisgarh reported a registration rate of more than 100 per cent, indicating the possibility of duplicate and fraudulent registrations.

Cess collected for and spent on construction workers

Source: Ministry of Labour and Employment (2019): “Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 278”, Lok Sabha, New Delhi

Moreover, the collection of Cess for the BOCWWB at the rate of 1 per cent of the total cost of construction and its proper distribution among workers is a major issue due to the implementation problem.

There is no proper mechanism for the collection of said Cess, its transfer to the concerned of BOCWWB, according to the assessment made by the 38th standing committee on labour of the Loksabha.

The committee also reported an under-assessment of Cess. As of 2019, only 39 per cent of the collected Cess has been disbursed to the workers.

Some of the states like Tamil Nadu (11.8 per cent), UP (10.5 per cent), West Bengal (9.8 per cent), Kerala (13.9 per cent), Bihar (9.5 per cent), Madhya Pradesh (8.3 per cent) and Andhra Pradesh (8 per cent) together contribute more than 70 per cent in the total construction gross value added (GVA), but their contribution to the total Cess amounts to only 37 per cent.

In 2019, Kerala and Bihar managed to collect only 3.9 per cent and 3.24 per cent of the Cess, respectively. On the other hand, Karnataka and Maharashtra, which contribute 6.9 per cent and 5.8 per cent in terms of the national GVA by the construction sector, collected 10 per cent and 15 per cent of the Cess, respectively.

However, in spite of being the biggest collector of Cess, Maharashtra spends very little (5.4 per cent), while, Kerala (120 per cent), Karnataka (89 per cent), Chhattisgarh (84 per cent), Madhya Pradesh (54 per cent), Rajasthan (55 per cent), Odisha (77 per cent), Punjab (54 per cent) and West Bengal (45 per cent) are the states who spend more than the national average.

Additionally, almost all the migrant construction workers would not be able to avail the benefits of the relief measures offered by the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), as such benefits can only be availed by the formal workers registered as contributing members of the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation.

This represents only a small percentage of the total construction workers in India, as estimated by the Periodic Labour Force Survey 2018-2019. The construction sector employs 83 per cent casual and 11 per cent self-employed workers, according to the survey.

Only 5.7 per cent of the workers work on a regular basis, of which 3.9 per cent are informal and only 1.6 per cent are regular formal workers.

Overall, only 2.2 per cent of the total construction workers are availing some kind of social security benefits, and only 1.5 per cent are regular workers eligible for benefits from the EPF, which clearly manifests the vulnerable condition of the construction migrant workers and their futures.

There is an urgent need for the administration to intervene and ensure that the gap between Cess collected and money spent on welfare activities through CWWBs is reduced. The silver lining has been the intervention by the judiciary in a few cases.

Recently, in July 2020, the Delhi High Court asked the Delhi government to see if registration of 10 workers with the BOCWW board can be verified online as the applications were made online.

The bench also said that there should be “no laxity” in registration of workers with the Board, through which they could get ex-gratia of Rs 5,000 during the pandemic. The state and the judiciary should step up and enable provision of benefits to all workers.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.