A significant proportion of the continent’s emissions reduction has been driven by outsourcing and other extraneous factors

In the past year, there have been many flip flops in authoritative projections of whether the European Union (EU) is on track to hit its Paris Agreement target of a 40 per cent reduction in emissions over 1990 levels by 2030. While last year’s edition of UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report estimated that the bloc was not on track to meet this commitment, the European Commission’s 2050 long term strategy document released around the same time argued that on the contrary, the country was on track to cut emissions by 45 per cent. This year, while the recently released Emissions Gap Report estimated that the bloc was on track to meet its targets, this has been challenged by The European environment —state and outlook 2020 report released on December 4 by the European Environment Agency. The report estimates that the continent is on track to reduce emissions by only 30 per cent by 2030 and thus not on track to meet its Paris Commitments.

The report has been published every five years since 1995 and this year marks the sixth edition. Covering a broad spectrum of environmental issues, it contains a chapter on climate change which notes the ongoing and potential impact of climate change on the EU, including the impact of climate change outside the continent which is fueling migration.

Noting that EU emissions in 2017 were 22 per cent lower than in 1990, the report argues that the decrease in the energy intensity of GDP has been the largest contributing factor. Energy intensity has been reduced by enhancing energy efficiency, as well as by the structural transformation of the economy away from industry towards services. What the report does not note is that with consumption continuing to grow unabated, industrial production (and consequent emissions) have merely been outsourced, most notably to China.

When net imports are accounted for, the EU’s total carbon footprint was 19 per cent higher than its domestic carbon footprint, which may be compared to its total GHG emission reduction of 22 per cent over 1990 levels in 2017. Britain, perhaps the most de-industrialised of EU member states, led the world in emissions from imports, which were as high as 40 per cent of its domestic emissions.

The report has neglected to mention another significant contributor to emissions mitigation in the EU since 1990. The fall of the Iron Curtain saw a drastic reduction in emissions in the Eastern bloc countries, as their economies collapsed, and this was followed by an ongoing structural transformation. Besides East Germany, 11 of these countries are now part of the EU.

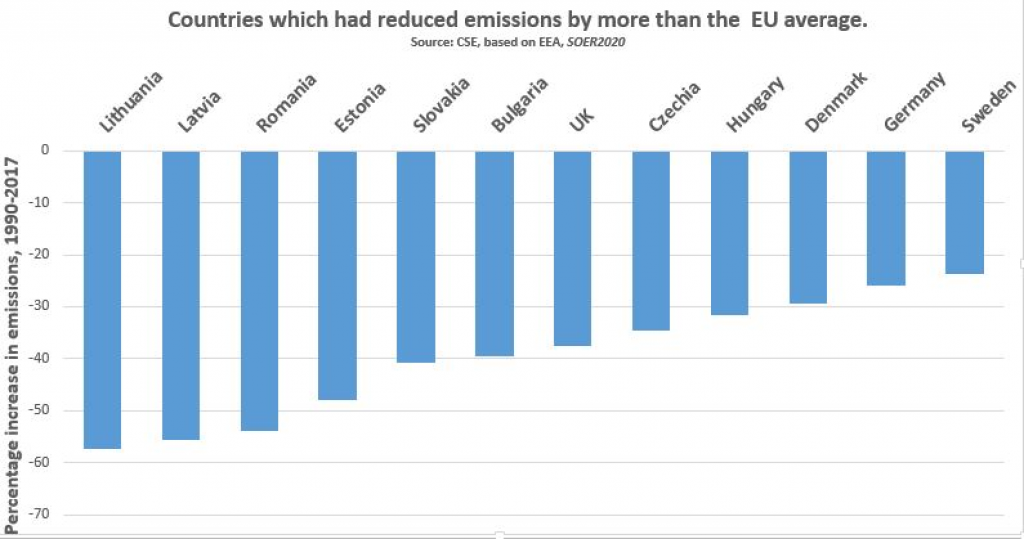

As per the data presented in the report, of the 12 EU countries (including Germany) which had reduced their emissions by more than the EU average, eight (excluding Germany) were once behind the Iron Curtain, including the all of the top 6 performers measured by percentage emission reduction (see Countries which had reduced emissions by more than the EU average).

Of the EU’s 28 member states, these eight former communist states (Lithuania, Latvia, Romania, Estonia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czechia and Hungary) alone accounted for 29.5 per cent of the 12.39 Gt CO2e net reduction in EU emissions between 1990 and 2017, despite their share of the EU’s population being only 11 per cent. "When the contribution of the other formerly communist member states of the EU (Poland, Slovenia and Croatia) is included, the Eastern bloc’s share of the EU’s net mitigation rises to 35 per cent. This substantial reduction in emissions, fueled by historical events rather than by concerted climate action, is a textbook case of what the Paris Agreement’s calls “differing national circumstances”. This strongly indicates that the EU’s climate targets must be much more ambitious.

Major economies amongst the laggards were Italy, France and the Netherlands (see Countries which reduced emissions by less than the EU average).

Six EU countries have actually increased their emissions since 1990, led by Cyprus whose emissions increased by over 55 per cent (see EU countries whose emissions increased, 1990-2017).

In the EU, emissions from some large industrial sources are governed by an EU-wide carbon market called the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), while emissions from other sectors are covered by what is called the Effort Sharing Regulation (formerly called Effort Sharing Decisions) which allocates national targets. Of the net reduction in emissions between 2005 and 2017, the report notes that two-thirds was accounted for by sectors covered by the ETS, even though these sectors accounted for only 40 per cent of all EU emissions.

This does not, however, indicate that carbon markets are a more efficient means of emissions reduction. As the report notes, the post-2008 economic slowdown has affected sectors covered by the ETS disproportionately, and this industrial contraction has led to a significant reduction in sectoral emissions. When emissions from energy supply were allocated to the end-user sectors, the largest emission reductions in the period following the economic recession were largely accounted for by industry as a whole.

Despite these overall impressive gains made in the past, the report notes that recent projections by EU member states indicate that the EU is not on track towards its 2030 climate and energy targets. The report notes that recent trend has not been encouraging, with primary energy consumption rising since 2014 and the growth of renewables has slowed down since 2015. Thus the report argues, the trajectories needed to meet the national targets are becoming steeper.

According to the report, EU is on track to reduce emissions by only 30 per cent by 2030 over 1990 levels as against its Paris Agreement target of 40 per cent. It estimates that even some additional normal measures will only result in a 36 per cent emission cut.

The EEA report argues that a complete decoupling of emissions from economic growth is impossible in a fossil fuel-based economy. However, fossil fuels are still the largest source of energy and emissions in the EU, contributing about 65 per cent of final energy consumption and almost 80 per cent of all emissions. Much of the EU’s historic emissions reduction has been the result of a shift from coal to another (albeit less carbon intensive) fossil fuel, natural gas. The contribution of this transition to overall emissions mitigation is particularly substantial in countries such as the UK which were early to the gas boom. The report emphasises that efforts to develop renewable energy are no longer enough. The continent needs to substantially step up the pace at which it decommissions its fossil fuel infrastructure.

But a European energy transition, even one that just eliminates coal (and replaces it with natural gas rather than renewables) is just not happening. While Brussels seeks to end coal-fired generation by 2030, the plans of Poland (where coal accounts for 80 per cent of power generation) do not even envisage a small reduction in generation before that year. Similarly, despite its championing of renewables, coal continues to be a large part of the reason why Germany’s per capita emissions are 50 per cent higher than those of France and Italy. Driven by pressing political and environmental concerns other than climate change, Germany's current focus in the energy sector is on replacing its nuclear generation capacity which is due to be phased out by 2022. In January this year, the country's official Kohlekomission recommended a 2038 phase-out date, but there has been little progress since.

Even if Germany moves on the issue, it is likely that coal will merely be replaced by gas, as effectively admitted by Angela Merkel on multiple occasions. The country’s preparations for the coal phase-out are thus dominated by plans to buy more gas from Russia through the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

A just transition requires countries to mitigate the impact of the fossil fuel phase-out on workers and communities involved in the industry; this was emphasized in the Silesia Declaration at last year's CoP in Poland. Nevertheless, Europe needs to move rapidly on phasing out coal, as well as fossil fuels more generally as it has the capacity to make the transition just.

Besides pointing out that the EU is grossly off track in meeting its mitigation targets, the report also mentions that all countries’ targets need to be more ambitious. The EU’s Paris target just about makes the cut in being rated “Sufficient” to slow global warming according to a grossly flawed report published earlier this year; a conclusion being widely peddled by European media houses such as The Guardian. While the EU Parliament passed a non-binding resolution calling for a 55 reduction in emissions over 1990 levels by 2030, EU negotiations in that direction have made little progress in the past year, with Germany being an important holdout. Even this 55 per cent cut will not put the EU on track to meeting its fair share of the mitigation burden required to limit the global mean temperature rise to 2°C, let alone 1.5°C, according to the Climate Action Tracker, a collaborative effort between Climate Analytics and the New Climate Institute, both based in Germany.

Also ongoing are painstaking negotiations to set 2050 as the target year for the EU to achieve net-zero carbon emissions, with Poland leading the delay. It may be mentioned that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2018 report on Global Warming of 1.5°C has set 2050 as the target date for the world as a whole. Equity demands that developed countries achieve net-zero earlier, around 2030. A 2050 target for net-zero carbon emissions is, in any case, is barely more ambitious than the EU’s existing long term target of cutting GHG emissions by 80-95 per cent by 2050.

Thus both on setting ambitious targets and doing the hard work needed to implement them, the continent needs to clean up its act.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

India Environment Portal Resources :

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.