Locusts have returned to India in just two months and are spreading to new territories. Has climate change added another layer of stress and uncertainty?

It’S May 27, 2020. A few minutes past 11 am. Down To Earth reporters had just arrived in Pachgaon village, Dholpur district, Rajasthan to enquire about desert locusts that are crossing over to India way ahead of the monsoon rain and invading new areas.

As if on cue, a huge swarm, resembling a long rust-coloured low cloud, appeared from nowhere. It swelled forward, taking over the sky and nearly obliterating the desert sun. Bewildered, residents ran out of their homes and gathered in the open.

Before they could get a grasp on the situation, millions of locusts started falling like hail and clung to everything that looked green. Within no minutes, trees and bushes turned into ragged mounds of glistening brown. Some leaned over to touch the ground — tropical grasshoppers weigh about 2-2.5 grammes. A few youngsters took photographs as others stood motionless.

It was for the first time the residents had seen something like this. Soon, the severity of the situation dawned on them. Some residents fetched their utensils and started banging them. Ram Babu, a farm worker in his 60s, rushed to his farm to scare the pests away with a piece of cloth.

He repeated the exercise for almost an hour in the 46°C heat. “I saw on the news yesterday about locust attacks in Jaipur, but did not think they would attack our village too,” he said, trying to call the land owner to inform him about the attack.

The nervous clamour of people did not let the swarm stay in the village for more than 40 minutes. In that short period, Babu lost almost one-fourth of his pumpkin crop planted on 3.5 bigha (0.3 hectares) land. Peepul, babool and keekar (Prosopis juliflora) trees looked strange with almost bare branches and punctured leaves.

Only a few insects were fluttering about when district agriculture officials arrived at Pachgaon. They were on alert from the night before and had tracked the swarm with the help of their counterparts in other districts and the Locust Warning Organization (LWO) — a unit under the Union Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare that runs the world’s oldest national locust monitoring system.

“At 5:21 am, I got a call from Karauli district that the swarm that settled on the forest for the night had started moving and the wind direction suggested they could enter Dholpur,” said Dayashankar Sharma, deputy director at the district agriculture department. His team of 25 officers soon left for the bordering villages and alerted residen ts to resort to dhwani aur dhuan (sound and smoke).

At around 7.15 am, a 10-kilometre-long swarm crossed into Dholpur at Jasora village.

The swarm moved at 25-30 km per hour. Officials were on their toes. “They were carrying insecticides that can be sprayed only when the insects settle at night. So, they joined the residents in stoking up the fire and beating utensils,” said Sharma, who waited at Saipau village road.

It was supposed to be the next stopover for the swarm. But because of smoke from nearby brick kilns, it diverted its route and entered Pachgaon.

“The ones left behind would become food for lizards or birds,” said Sharma. He was relieved that his team and the others did not let the swarm settle anywhere in the district and could drive it away before sunset. Because that’s the time they dread, when locusts are on the move.

This gregarious species usually flies during the day and lands just before sunset. If they settle on a farm, they devour whatever green they spot before flying out in the morning.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which considers desert locusts as the “most dangerous of all migratory pest species” and runs the centralised monitoring and information service, Locust Watch, a swarm of one sq km contains over 40 million locusts that can eat the same amount of food in a day as 35,000 people.

Farmers of Sri Ganganagar and Bikaner districts know this voracious nature of the pest only too well.

The districts are part of the state’s cotton growing belt where agriculture has been made possible because of the Bhakra, Indira Gandhi and Gang canals. In the months of May and June short cotton plants dot the fields in this arid region.

But this year most farms wore a desolate look. Mahaveer Saran, who owns 5 hectares in Beenjhbaila village, narrates how locusts have pushed his entire village into penury overnight.

“A gigantic 40 sq km swarm invaded our village on May 27. Some of my neighbours ran to the market to buy firecrackers as I made calls to the agriculture office and organised people to bang utensils, but to no avail. The officials did not show up. By the time the swarm left around 12 pm the next day, they had eaten every leaf and shoot off our farms,” he said.

Earlier that month, on May 10, an equally huge swarm invaded Lalawali village in Bikaner and destroyed all cotton crops in two hours.

Initial estimates by officials with the agriculture department showed locusts mostly destroyed cotton crops in the state — 4,500 ha in Sri Ganganagar, about 9,000 ha in Hanumangarh, 830 ha in Bikaner and 70 ha in Nagaur. On an average, every hectare produces 2,000 kilogrammes of cotton that is sold for Rs 1.20-Rs 1.40 lakh. Farmers said they never saw such huge swarms so early in the year.

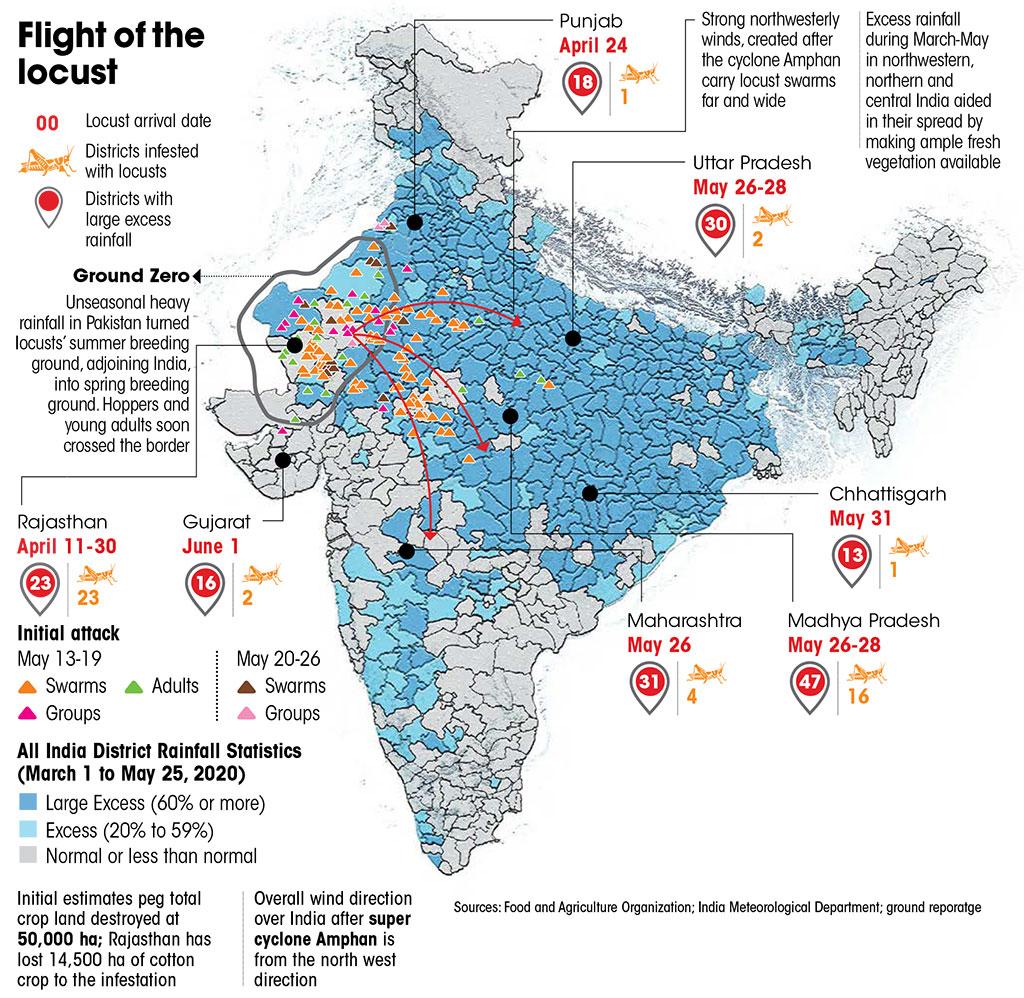

This trans-border pest usually enters the scheduled desert areas of India from Africa, Gulf and Southwest Asia via Pakistan just ahead of the monsoon season for summer breeding and then returns around October and November towards Iran, Gulf and Africa for spring breeding. But this year, according to the Union agriculture ministry, they were sighted as early as April in the border districts of Rajasthan and Punjab.

Residents of Lalawali said with this early arrival, locust attacks have become an unending ordeal for them. Last year’s attack, considered a major locust invasion after almost a decade, had also begun way ahead of the season, in May 2019 and continued till February this year.

Data with the ministry showed 11 districts in Rajasthan, two in Gujarat and one in Punjab were exposed to locusts during the period.

“Now, they are here again after a gap of just two months,” said Babulal Shaswat of Lalawali. On May 10, Shaswat and many other farmers in his village lost their third consecutive crop to locusts in less than a year. “In September last year, they devoured my standing cotton crop; in February this year, chana (black gram) crop and now, American cotton,” said Shaswat.

To recover losses, several farmers in the village took loans and sowed cotton again. But it’s too hot for the seeds to germinate. Shaswat said he is in a fix.

He plans to wait till the monsoon and then sow groundnut. But people said the locusts will come back during kharif.

“I do not know how I will pull through. So far, I have accumulated a loan of Rs 4.5 lakh and have neither paid my instalments nor the school fees for my children since last year. My family is surviving on remittance sent by my brothers working in Bikaner,” said Shaswat, adding that such an invasion had occured two to three decades ago. But this time the swarms are just too big and too aggressive.

They are also unusually pink. “Usually sexually mature, yellow-coloured locusts come first,” said BS Yadav, assistant director, agriculture department, Jaipur.

They tend to stay on the ground and move less once they mate. It’s easier to spray on them and contain their spread. But this year, the presence of hoppers (freshly hatched locusts that are yet to develop wings) has been reported since April 11 and pink immature adults since April 30.

These younger pests tend to settle on taller trees compared to crops. They are like children full of energy and fly away as soon as you go near them, making it difficult to manage them, said Yadav, adding it was unusual for younger locusts to arrive at this time.

Their behaviour also changed because of the early arrival, said KL Gurjar, deputy director at LWO. During monsoon and winter nights, their wings get stuck due moisture or dew and they cannot fly until the sun is out. Since the weather is dry now, they are able to fly at night, making control operations difficult.

With an ability to ditch control measures, fly high and cover long distances, these swarms are now moving beyond the scheduled desert areas, taking people by surprise and posing challenges for LWO that operates with a limited staff.

In Jaipur district, which reported massive locust attacks in the last week of May, Sachin Yogi, a 24-year-old wedding photographer, said, “I have only heard my grandfather talking about locusts”.

On May 26, some 30 LWO officers, armed with a drone and six ultra-low-volume sprayers, Ulvamast, chalked out a war plan of sorts with 16 state government officials manning four fire tenders to destroy a 40 sq km swarm that had taken residence at Maharkalan in Karanpur village.

They were out on the roads all night, spraying solutions of highly toxic insecticides like chlorpyifos and lambda cyhalothrin on every tree, bush and other vegetation in the area. The drone was also employed to spray insecticides on the hillocks of the Aravallis that border the district on one side.

At the end of the operation, it was hard to tell if there was anything apart from a few random locusts flying around. “A swarm, 180 sq km in size, entered India on May 22. We destroyed a part of it at Nagaur district. The remaining came here,” said a LWO official. But as soon as sunlight hit the trees, thousands of locusts burst out of the canopies, blinded by chemical sprays yet eager to fly away.

In Uttar Pradesh, the district administration of Jhansi carried out control operations thrice between May 22 and 27.

“LWO officials have been staying in Jhansi since the district was attacked by a swarm,” said Kamal Katihar, deputy director of the district agriculture depar tment. “While we use chlorpyrifos, they handle the highly poisonous Malathion96. Besides, we never had the need for the chemical as this is the first attack in Jhansi after 30 years,” said Katihar.

While in Uttar Pradesh, locusts have invaded two districts, they have spread to 40 of 52 districts in Madhya Pradesh within a week of entering the state. In Hoshangabad district, deputy director of agriculture Jitendra Singh said moong is close to harvest now.

“So as soon as the locusts entered the district on May 23, we deployed four fire engines and sprayers mounted on tractors to spray lambda-cyhalothrin early in the morning. Crops in our district have been saved,” he added.

Though the agriculture department claimed it destroyed 40 per cent of the locust population, swarms were active in eight districts, including Bhopal in the first week of June. Some crossed Madhya Pradesh to reach Koriya district, Chhattisgarh on May 31.

As of June 7, locusts had spread to 44 districts in seven states; control works were done on 70,728 ha and, nine states are on high alert for a possible attack. India had never faced a locust attack of such proportion.

This was first published in Down To Earth’s print edition (dated 16-30 June, 2020)

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.