It provides the oldest skeletal evidence of leprosy

It provides the oldest skeletal evidence of leprosy

a museum in Pune has a collection of thousands of bones and skeletons excavated in India. Among them is a

4,000 year old skeleton of a man believed to be 37 years when he died. This skeleton was found buried at Balathal, about 40 km north-east of

Udaipur in Rajasthan.

What sets it apart from other skeletons at the museum of the Department of Archaeology, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, is

that it provides the oldest evidence of leprosy in human beings. The skeleton called specimen 1997-1 was analysed by anthropologists and

biologists from Deccan College and from Appalachian State University, North Carolina, usa.

|

|

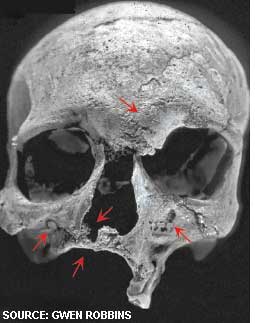

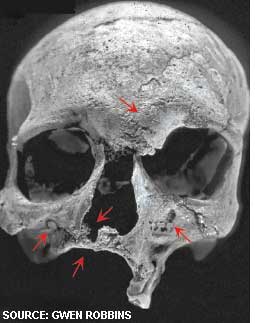

| Excavated skull showing signs of leprosy |

| SOURCE GWEN ROBBINS |

"The most peculiar thing about this man was that although he does not seem to have had any congenital defect, his nose, teeth and mouth show

signs of erosion," said Veena Mushrif Tripathy, anthropologist at Deccan College who was involved in excavation. Bones beneath the skull--the

vertebral column, ribs, shoulder and pelvic bones--are incomplete and fragmentary. Many ends of the foot bones are missing. Joints are

degenerating and finger tips, legs and the nose are damaged. "This is proof enough that the specimen 1997-1 had leprosy," said

Tripathy.

Every year leprosy affects 250,000 people worldwide and is one of the least understood infectious diseases. Partly because

Mycobacterium

leprae that causes the disease is difficult to culture and has only one other animal host, armadillo, a small mammal with a leathery armour

shell.

Previous archaeological evidence of leprosy was dated to 300-400 BC in Egypt and Thailand. The earliest widely accepted textual evidence for

leprosy was 600 BC Asian texts. Some translation of the Atharva Veda, composed before the first millennium BC, also referred to leprosy, but

this was not widely accepted. The skeletal evidence from Balathal provides support to this translation, pushing back the date for the earliest

textual reference to the disease by over 1,500 years. "Our study indicates lepromatous (multibacilliary) leprosy existed in India since 2000 BC,"

said Tripathy. Lepromatous leprosy is found in those with very little or no immune resistance to the bacterium.

The study also supports a hypothesis about prehistoric transmission routes for the disease. The exact time of the first infection, geographic origin

and pattern of transmission of leprosy are still under investigation, but a comparative genomic research suggests the leprosy pathogen evolved

either in east Africa or south Asia during late Pleistocene (40,000 years ago).

The presence of leprosy in a man from the post urban phase of the Indus age suggests that if leprosy originated in Africa, the disease possibly

migrated to India during the third millennium BC at a time when there was substantial interaction among the Indus civilization, Mesopotamia and

Egypt. "This evidence should be an impetus to look for additional skeletal and molecular evidence of leprosy in India and Africa to confirm the

African origin of the disease," Tripathy added.

Specimen 1997-1 also strengthens historical evidence showing leprosy spread from Asia to Europe with Alexander the Great's army.

Understanding the origin and prehistoric transmission of leprosy can lead to new insights into the evolution of infectious diseases and could be

helpful in eradication efforts, said the study published in the May 27 issue of

PLoS ONE.

Gwen Robbins of the Department of anthropology, Appalachian State University, is now trying to extract bacterial

dna from the skeleton for more such clues. According to her, the skeleton demonstrates the disease was present during

a period of increasing urbanization in India and Pakistan, supporting the long held association between leprosy and urban life.

The team plans to examine skeletons from Indus sites like Harappa in Pakistan's Punjab, Farmana in Haryana and Kalibangan in Rajasthan to

ascertain whether leprosy existed there.

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

It provides the oldest skeletal evidence of leprosy

It provides the oldest skeletal evidence of leprosy

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.