Putting a stop to unmindful concretisation of lake beds and drainage channels can save cities from disastrous floods

.jpg)

As Jammu and Kashmir battles one of the worst floods in decades, environmentalists have blamed encroachment of the wetlands in the valley as the main reason for this devastation.

The Kashmir valley is dotted with wetlands which play a very important role in controlling flood in the region. Apart from natural ponds and lakes, the valley also houses other types of wetlands, like rivers, streams, riverine wetlands, man-made ponds and tanks. As per a report of Department of Environment and Remote Sensing, there are 1,230 lakes and water bodies in the state with 150 in Jammu, 415 in Kashmir and 665 in Ladakh. Dal Lake, Anchar Lake, Manasbal and Wular Lake are some of the larger wetlands in the area which are facing a major threat due to urbanisation.

Dal lake, one of the world's largest natural lakes, covered an area of 75 sq km in 1200 AD. The lake area almost reduced to one-third in the eighties and has further reduced to one-sixth of its original size in the recent past. The lake has also lost almost 12 m of depth. "Massive encroachments and erection of many structures and hotels have led to the reduction in the size of the lake," says Manu Bhatnagar, principal advisor in the natural heritage division of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), Delhi Chapter. INTACH's Jammu and Kashmir chapter had observed that construction in low-lying areas of Srinagar, especially along the banks of the Jhelum, had blocked discharge channels of the river almost five years ago.

Just like Dal, encroachments have also happened on the banks of one of the most prominent rivers in the state, the Jhelum that passes through Srinagar, the summer capital of the state. In 2005-06, the department of Irrigation and Flood Control launched a drive to remove encroachers along the Jhelum channel. However, the drive was not to manage the natural drainage of Srinagar but to beautify the river front. The waterbodies in Jammu are also under threat. The city was once famous for its traditional ponds and tanks which have been erased to house commercial complexes and parks in the city. This practice is repeated across India. Every year floods are reported from Ahmedabad, Bhopal, Bengaluru, Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Surat, Rohtak, Gorakhpur, Guwahati due factors like inadequate drainage systems, housing on flood plains, natural drains and river beds, and loss of natural water storage areas. These factors demonstrate how rapid urbanisation in and around the city limits make flood events inevitable in the urban areas. In the last decade alone, a number of incidents of urban floods were reported – Mumbai (nine times), Ahmedabad (seven times), Chennai (six times), Hyderabad (five times), Kolkata (five times), Bengaluru (four times) and Surat (thrice).

Mumbai case point

Just like Srinagar and Jammu, many urban centres of India are failing to manage the drainage channels which are the stormwater drains. Unplanned development is taking place on the channels which are supposed to empty themselves in the nearby wetlands. In July, 2005, Mumbai learnt its lesson for tampering with nature. The city received over 900 mm rainfall in 24 hours and this killed almost 450 people. With flood came fever, dengue, diarrhoea and cholera. It has been seen that in 1925 as much as 60 per cent of the land area in the city was for agriculture and forest. In the beginning of 1990, the area got reduced to just half. The six basins of streams that criss-crossed the city, carrying its monsoon run-off, had been converted into roads, buildings and slums. The city came to know that it had a river called Mithi which had been marked as stormwater drain in the Environmental Status Report 2002-2003. The city is almost built over the river and untreated sewage and garbage choke the waterways of the river. In 2006, the corporation ordered eviction of the slum colony near the river to clean the river. Protests followed. Nothing concrete happened; there were plans for more buildings encroaching the river. Thus the city faces floods again and again.

Repeated mistakes

The stories of wetlands in Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Guwahati seem to be strikingly similar. In the beginning of 1960, Bengaluru had 262 lakes, but right now only 10 of them hold water. Hyderabad is also losing its waterbodies. Between 1989 and 2001, 3,245 ha of waterbodies were lost, which is 10 times the size of Hussain Sagar, the major waterbody of the city.

Phanisai, researcher with non-profit Namma Bengaluru Foundation, explains that the city has both upstream and downstream lakes. The upstream lakes feed the downstream lakes through “rajkalve” (stormwater drains). He adds most of these drains in the city have been encroached, hence there is no outlet for the lakes upstream, and hence there is rise in these lakes causing flooding in the neighbouring areas. The downstream lakes are also not getting any feed from the upstream lakes and they are encroached in due course of time. Just like Mumbai, Bengaluru also faced flooding in the monsoon of 2005; the situation was worsened by choked drains and unauthorised development along the lakes.

In Hyderabad, the flood threats are evident because of encroachment of the floodplain of the Musi, the main river of the city, according to environmentalists. The city already faced a disastrous flood in 2000 but still the authorities did not learn any lesson. Only few encroachments were removed after a high court order.

In Guwahati, the beels or the ponds used to collect huge amount of rainwater that flowed from the surrounding hill catchments. Rampant encroachment almost killed the beels and also the channels feeding them, which makes flood a regular feature in the city, says Partha J Das, programme head of Guwahati-based NGO, Aranyak. He adds Guwahati is facing the consequences of mismanagement of waterbodies and river. It’s not just encroachment, but garbage dumping is also choking the drainage channels and the waterbodies of the city. Unplanned rapid urbanisation during post 2000 in most of the cities led to large-scale conversion of watershed area of lakes to residential and commercial estates. The catchments also got deforested or degraded; this caused huge silt movement in the catchment. The silt flowed directly into the waterbodies clogging them. This results in flash floods in the region, explains Das.

The urban waterbodies are under the land owning agencies like departments of revenue, fisheries, urban development, public works, municipalities or panchayats. These departments fill up the waterbodies and show these as cases of change in land use patterns. The vital roles played by the urban waterbodies in flood moderation and groundwater recharge are completely underestimated, unaccounted and overlooked, says Jasveen Jairath, regional coordinator of Hyderabad-based NGO, Save Our Urban Lakes. Jairath, who is fighting to save the lakes of Hyderabad, adds that one should not disturb the drainage flow and the storage capacity of the wetlands. This will give rise to floods and droughts in the city.

Sukhdev Singh, chief executive officer of Delhi Parks and Garden Society under Government of Delhi says most of the urban waterbodies in Delhi are encroached because they are dry. The catchment and the waterbodies are under different agencies and conflict of interests between two agencies kill the waterbodies. He quoted the example of Badkhal lake in Faridabad, very close to Delhi, which has become dry as the catchment has been degraded due to mining. Singh says waterbodies should be under a separate department. Right now Delhi waterbodies are under different agencies for whom their conservation is not a priority.

What does the law say?

The lakes and waterbodies of India are directly influenced by a number of legal provisions and regulatory framework. Article 48-A of the Constitution states: “The State shall endeavour to protect and improve environment and to safeguard the forests and wild life of the country”. Similarly, Article 51-A (g) says it is the fundamental duty of each citizen “to protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures.”

Few cities like Guwahati and Kolkata have taken steps to preserve the waterbodies. In Guwahati, the state government, pushed by the judicial intervention, passed the Guwahati Water Bodies (Preservation and Conservation) Bill of 2008. The aim was to preserve wetlands and to reacquire lands in the periphery of the waterbody for its protection. Earlier in 2006, the East Kolkata Wetland Conservation and Management bill was passed to protect some 12,000 ha of wetland. This bill includes provision for penalties—Rs 1 lakh for encroachment. The Andhra government’s ‘Water, Land, Trees Act’ empowers state agencies to take steps to protect water bodies and to prevent conversion. The Act also requires measures to permanently demarcate the boundaries of the water bodies and to “evict and prevent encroachment”. The Kerala Government has also came out with Kerala Conservation of Paddy Land and Wetland Act, 2008. This Act provides for imprisonment for not less than six months and fine up to Rs 1 lakh.

People concerned about lakes have been forced to go to court because there was no other grievance redressal mechanism to identify and protect the city’s waterbodies. Giving in to the clamour for a national regulation, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), issued a rule for conservation and management of wetlands in December, 2010, under the provisions of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, called the Wetlands (Management and Conservation) Rules, 2010.

According to Sanjay Upadhyay, a leading environmental lawyer, one has to give teeth to the law. Once the wetland is notified under the Act then only it can be protected, otherwise the Act is of no use. If one fails to notify a wetland, then that wetland cannot be protected. Upadhyay adds Town and Country Planning Act should take care of the wetlands. But the municipal bodies that implement this act does not have technical capacity identify a wetland.

Bhatnagar of INTACH adds that government apathy towards the wetlands causes floods in the urban areas. In the state of Jammu and Kashmir, lack of implementation of strict laws allowed people to construct on the flood plain areas. Stringent laws should be in place to protect the urban waterbodies, believe all the lake warriors.

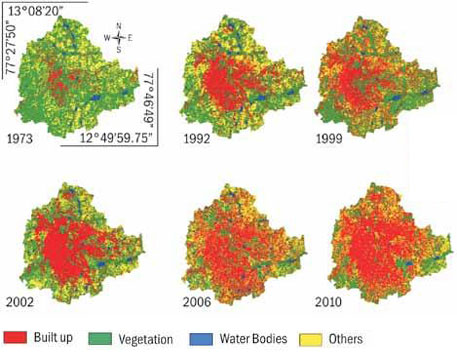

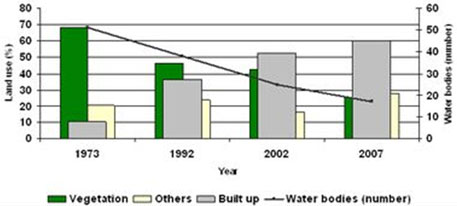

Impact of urban land transformation on water bodies in Srinagar city, India

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.