The new declaration, that renews the global pledge to achieve universal health coverage by 2030, is a step forward but still lacks on several fronts

On October 25, 120 UN member countries signed the Astana Declaration, vowing to strengthen primary healthcare and achieve universal health coverage by 2030. This is the second time the world took this pledge. In 1978, 134 nations signed the Alma-Ata Declaration with the same pledge. The reason behind the need for reaffirmation is clear —the world has failed to meet the targets set 40 years ago. Though Alma-Ata was signed to ensure health for all, its progress was uneven, with several countries missing out on several indicators set under the declaration. While the Americas, Europe and Western Pacific countries performed well, according to papers presented at the Astana conference, South Asia and Africa lagged.

The reason, as the 2006 World Health Report indicates, was the needs-based shortages in primary healthcare, which was the highest in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The report identified 57 countries, mostly in SSA, that had less than 23 health professionals, including doctors, nurses and mid-wives, per 10,000 people. As a result, 80 per cent of basic maternal and child health services could not be provided and the world failed to meet one of the main thrusts of Alma-Ata, which was reproductive health. Shortage of funds also affected the progress of this indicator. A poll conducted among the participants at Astana revealed that 59 per cent of the countries spend only 19 per cent of their national health budget on sexual, reproductive, maternal, new-born, child and adolescent healthcare. The positive feedback of the poll was that in 29 per cent countries, 60 to 69 per cent of women opt for institutional delivery.

Missing the mark

David Sanders, professor emeritus and founder director of the School of Public Health at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, cites a fundamental problem in the approach to this global pledge. “It has been mediocre because of political and economic reasons.

This is because of the lack of a new economic order to address inequities, which determine access to nutrition, safe drinking water and sanitation.

These, in turn, reflect on the health of a population. As adequate policies were not framed to address these issues, Alma-Ata could not be implemented,” Sanders says.

He also criticised its implementation. “The way many countries implemented it is also very problematic. Governments are using public money to rope in the private sector in the name of insurance,” Sanders adds.

K Srinath Reddy, head of New Delhi-based non-profit Public Health Foundation of India attributes the failure of Alma-Ata to donor-driven agenda. “These focused on specific health issues, forcing recipient nations to abandon their commitment to the Alma-Ata on overall comprehensive primary healthcare,” he says.

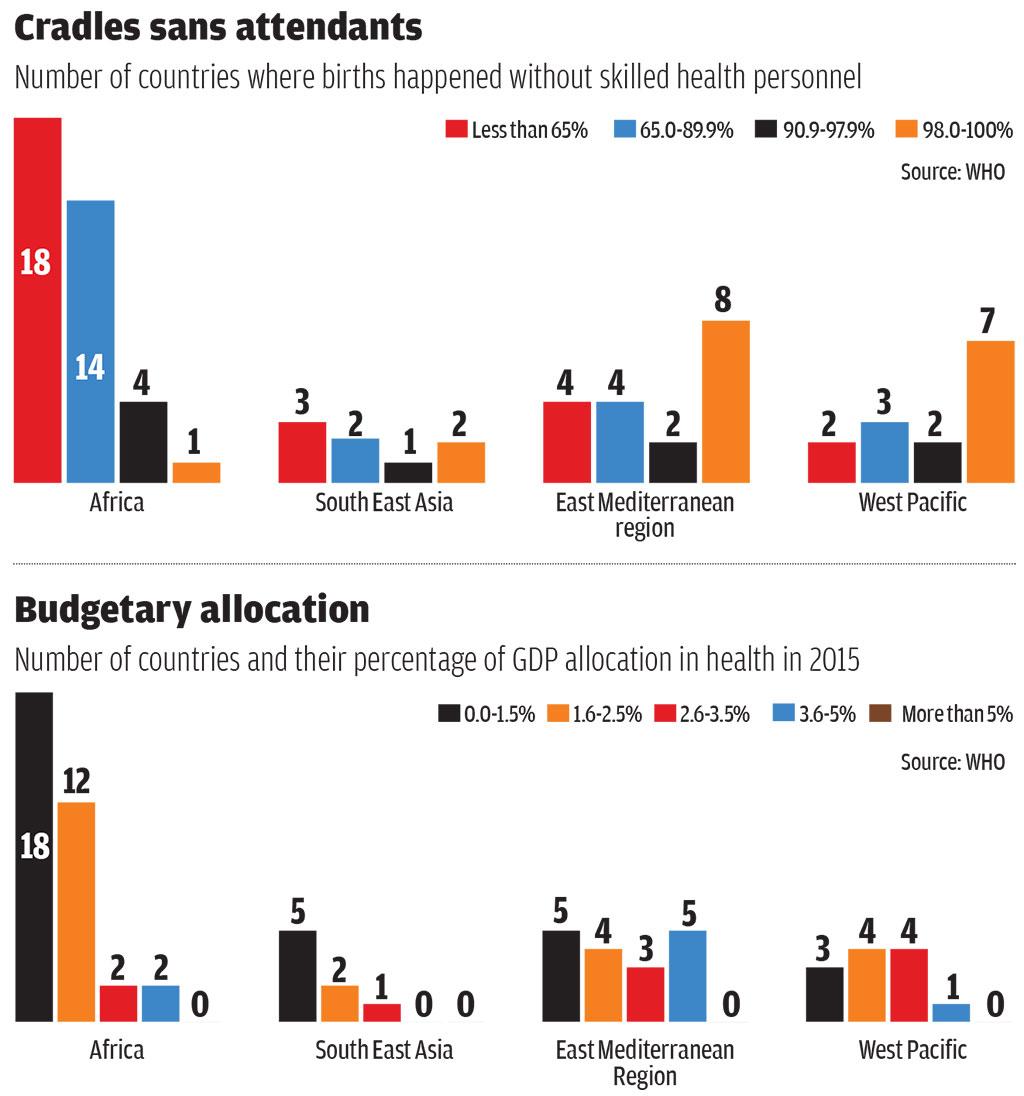

Down To Earth’s analysis of three indicators (see infographs) agreed upon at Alma-Ata also shows poor performance. Though globally, almost 80 per cent of live births occurred with the assistance of skilled health personnel between 2012 and 2017, disparities exist within regions. For instance, in more than 18 African countries, children were born without the presence of skilled attendants in 35 per cent of cases while only Guatemala in the Americas recorded this.

Regarding health spending, the governments of 22 countries in Europe spend 5 per cent of their GDP on health. While South East Asia spent 3.5 per cent in 2015, the East Mediterranean region spends just 1.6 per cent of the global health spending for 8.7 per cent of the world’s population.

Some countries have performed well in all the six World Health Organization regions. “In South East Asia, Sri Lanka and Thailand; in Eastern Mediterranean, Iran and Qatar; and, in the Americas, Canada, Brazil and several Caribbean countries have done well,” says Reddy.

Looking forward

Though Astana is a step forward, a statement released by the Peoples’ Health Movement, an international non-profit based in South Africa, shows it is still lacking on several fronts. It says that Astana views primary healthcare as just a corner-stone for Universal Health Coverage even though it is a much broader concept. Though the Astana Declaration recognises the risk factors for premature deaths and non-communicable diseases and attributes them to both human-made and natural causes, nowhere does it recognise the economic and political reasons responsible for these.

A report, The Astana Declaration: the future of primary health care? published in The Lancet on October 20, 2018 says, “As populations age, and multimorbidity becomes the norm, the role of primary health-care workers becomes ever more important.” It concludes by saying that leadership after the Astana pledge is essential to rejuvenate all the aspects of primary healthcare.

(This article was first published in the 16-30th November issue under the headline 'The lament continues'.)

We are a voice to you; you have been a support to us. Together we build journalism that is independent, credible and fearless. You can further help us by making a donation. This will mean a lot for our ability to bring you news, perspectives and analysis from the ground so that we can make change together.

Comments are moderated and will be published only after the site moderator’s approval. Please use a genuine email ID and provide your name. Selected comments may also be used in the ‘Letters’ section of the Down To Earth print edition.