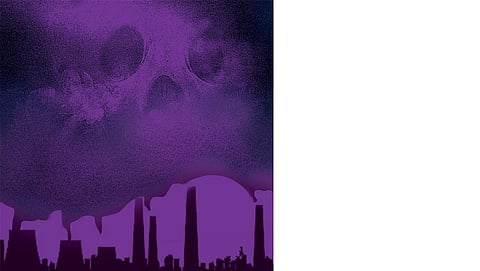

Air pollution, a great equaliser

Air pollution is deadly. This is no longer a question of debate. Most of us who live in the gas-chamber that our cities are know that the air is not fit to breathe. But what are we doing about it? This is where the matter gets murkier than the air we are forced to inhale. Let’s understand why we are not winning this battle for blue skies and clear lungs.

In 2019, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), as it is called, to fix the air quality of our cities. This move meant that instead of the Supreme Court, governments would drive the action on air pollution. Targets for clean air were set for 131 cities that had high pollution load. They were required to reduce particulate concentration by 20-30 per cent by 2024 from the base year of 2017; the target was later revised to 40 per cent by 2025-26 from the base year of 2019-20. All good you would say. Even better was the fact that the 15th Finance Commission provided direct grants to 42 cities and seven urban agglomerates with a population of more than 1 million for actions to curb air pollution. MoEFCC provided funds for the remaining cities. And with this, some Rs 20,000 crore has been earmarked for the five-year period till 2025-26. This is not all. Each state government and each city is required to make an action plan based on studies on the sources of pollution to decide on the priority of action. The funding is performance-linked and requires cities to show improvement in air pollution levels and an increase in the number of “good” air days, with the air quality index below 200 as the benchmark. In 2022, MoEFCC introduced a ranking called Swachh Vayu Survekshan to recognise the cities that had taken action to reduce deadly pollution. You would argue that all the elements are here for us to reduce the burden of pollution in our air.

But this is not the case. The fact is, in this focus on setting up the entire paraphernalia, the action that needs to be taken has been lost sight of. My colleagues have taken a deep dive into the programme and have found the following: The most problematic is that NCAP measures only PM10 as the key pollutant; this means, all action is linked to the control of PM10—not PM2.5, the tinier fractions of the particulate that are widely indicted for the disease burden. These are so tiny that they can enter the blood stream and cause heart diseases, not just asthma and lung problems. The fact is also that PM10 or the coarser particulates are dust-related, and dust is not a pollutant, per se. Dust becomes a health problem when it is coated with toxins that come from other sources, mainly from combustion-related sources like vehicles or industries. It needs to be addressed, but not without taking hard and often inconvenient steps to re-duce emissions from the growing number of vehicles on our roads; from the use of coal in industrial units without pollution measures; from the continued open burning of garbage and, of course, the wickedest of all, from the continued use of biomass for cooking food that not only fouls up the air but also adds to the health burden of women.

So, action linked to control this one pollutant, dust, is the most favoured of all, because it belongs to no one in particular, unlike emissions from vehicles for which manufacturers would be held to account and from coal-burning power plants where power producers would be responsible. The review by my colleagues has found that 64 per cent of the money for air pollution control has been spent on road paving, road widening, pothole repair, water sprinkling and mechanical sweepers. However important the repair of road potholes may be, we who live in India know that these are never ever done; it is a perpetual exercise in futility and all in the name of air pollution control.

Clearly, this is not the way to go. The other problem is that there is no real link between reduction in PM10 levels and the action that cities have supposedly taken to achieve the progress. In fact, there is often an inverse relationship—cities that rank high on reducing pollution are at times the lowest in terms of action taken. This mismatch leads to policy confusion; it tells us nothing about what must be done to combat pollution and what is working and where.

The much-heralded governmentalisation of air pollution agenda cannot become an exercise to move the files and tick the boxes. It must be about action. This is about the air we breathe, and let’s be clear that air pollution is a great equaliser; it impacts the rich and the poor equally. This is not like the case of water pollution, where the rich can maintain the quality in-house or use bottled water. This is about air, which we need to breathe at all times, and no number of air purifiers can clean the air everywhere.