Papers show what lay behind Condé regime’s Ebola denialism in Guinea

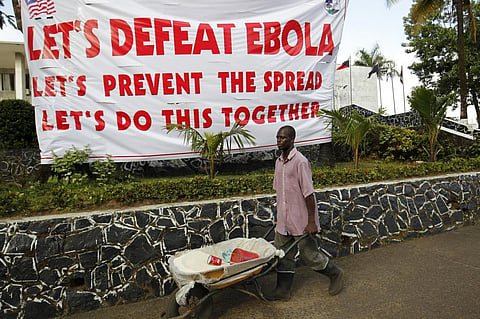

More than 11,300 people died when the Ebola virus ripped through three West African countries — Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia — from 2014 to 2016. It was the worst Ebola outbreak in known history.

But the differences in responses to the outbreak, particularly in its early stages, were puzzling. While the outbreak worsened during the March-October 2014 period, Liberia and Sierra Leone emphatically sought global assistance. They and other states highlighted the danger the virus posed to local, regional and global stability. Guinea’s reaction, in contrast, was to downplay the epidemic. President Alpha Condé insisted his government had the outbreak under control.

As it’s one of the poorest countries in the world, with little infrastructure, and virtually no health infrastructure, why would anyone believe President Condé’s assertion?

For me, this reaction did not appear to be in line with the severity of the outbreak, its potential economic destruction, the general risks to the population, and Guinea’s overall stability.

I decided to find out why Guinea reacted this way. And I concluded that the reason was fear that Ebola would panic investors. Condé’s initial response was indicative of a pattern among some leaders to prioritise the perception of political and economic health instead of the health of their citizens. As in the current pandemic, this pattern is not unique to Guinea or to the Ebola outbreak

Behind Guinea’s Ebola denialism

In October 2014, I filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the US Departments of State and Defense for information and communiqués related to the Ebola outbreak from the US embassies in Conakry, Freetown and Monrovia.

After three years of prodding and waiting, both agencies delivered sets of documents that showed a blunt assessment of events in Liberia and Sierra Leone during the March-October 2014 period.

But Condé told US embassy officials that Guinea had the outbreak under control. The documents presented a series of communiqués that provided assessments of the Ebola outbreaks in the three countries during the March-October 2014 period. The assessments were provided by high ranking US embassy staff, up to the level of US ambassadors.

What I found confirmed President Condé’s downplaying of the outbreak. It also revealed one of his potential motives in doing so.

The story these documents told revealed policy failures that had their roots in both Guinea’s underdevelopment and in the deeply corrupt relationship between mining interests and the government.

If you want to understand what a government’s priorities are, an examination of its budget spending can help. In 2017, the latest available data indicated that Guinea spent only 4.1% of its government budget on healthcare. But it spent 10.2% of its budget on its military. That number declined in 2020 to 8.2%, but was still double the healthcare expenditures.

Overall, Guinea ranks 178 out of 189 countries on the World Bank’s Human Development Index. The index is a composite measure of health, education and income. It’s used as a measure of human poverty and capability that extends beyond just income.

Guinea’s mining interests also played a role. As the Ebola epidemic was unfolding in March 2014 – after the Guinean government acknowledged the presence of the virus – corruption scandals and mining contract issues that had been simmering since Condé took office finally boiled up.

Condé’s government needed more investors to develop Guinea’s mining sector. The country is home to the world’s largest supply of high-grade bauxite, the key component in the making of aluminium, and one of the world’s largest untapped iron ore deposits.

For Condé, the opportunity to advance this and other projects came with the first US-Africa Leaders Summit held in Washington in August 2014. The summit was critical for kick-starting a new round of investment after the previous regime’s mining arrangements collapsed.

The Guinean delegation to the conference – the only one of the three Ebola-stricken countries to attend – explained that they thought the heightened attention accorded to Ebola in the run-up to the summit would unfairly refuel Guinea’s image as “too risky” and might scare off investors.

While the summit produced help in the Ebola crisis, Condé also conducted high level meetings with mining investors to discuss over US$20 billion in investments.

Ebola denialism in Guinea had its roots in a fear that Ebola would panic investors. On August 14, 2014 after the US summit, Condé ordered a national health emergency, months after the outbreak was declared. The delay in casting Ebola as a national emergency in Guinea contributed to growing infection rates and deaths in the country.

Quest for power trumps public welfare

Condé’s approach to the Ebola crisis and his courting of business and mining interests continued a history of African leaders who employ extraversion strategies. These strategies allow elites to marshal resources and finances that are derived from their external global relationships. Such leaders have opened their economies to investors, letting them divert resources for corrupt purposes that extend their political and economic control in the state.

Such policies provided the basis for Condé to consolidate power through a stronger patrimonial network and tighter personal and familial control over the country’s mining interests. That control gave him confidence when he sought to extend his time in office beyond the constitutionally prescribed two terms.

Condé got a third term in office in 2020. But his government was overthrown in a military coup in September 2021. The coup leader, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, cited Condé’s lack of leadership, his corruption, and Guinea’s lack of development as motivation.

Guinea’s lack of development, though not new, is particularly poignant as the country moves through its current COVID-19 wave, with little or no improvement in its basic and medical infrastructure. Notably, Doumbouya was quick to assure mining investors that their contracts were safe.

Future uncertain

Condé’s pursuit of mining interests during the Ebola crisis may have foreshadowed his demise as he tightened his grip over power and plundered the state’s wealth, as many before him did.

While Guinea’s people were happy to see him go, the country’s history of corrupt leaders and persistent underdevelopment mean hope for real change may be a dream under a new military regime.

Robert Ostergard, Jr, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Nevada, Reno, University of Nevada, Reno

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.