Book excerpt: How the ‘Pagri Sambhal Jatta’ Movement resonates with the 2020 anti-Farm Bills agitation

Excerpted with permission from Panjab: Journeys Through Fault Lines by Amandeep Sandhu, published by Westland, October 2019

The crisis is not only of Panjab. It is a national agrarian crisis. The reason Panjab is relevant is that this was the original laboratory of the so-called Green Revolution that later spawned the White (milk), Blue (fish), Golden (honey and fruits), Pink (onion), Silver (eggs), Red (meat and tomato), Yellow (oil seeds) and Round (potato) Revolutions.

These are revolutions that encompass the entire rural agrarian sector which is more than half of our nation’s population. As we hear more voices from the field, we now know every revolution has had its after-effects. Why could the nation not learn to correct itself from Panjab, the original laboratory and in the process, not let Panjab slide?

It begets the question: is what we call the Green Revolution really a Green Revolution? In political terms, a revolution is when the people overthrow the apparatus of power.

But owing to the nomenclature of the Industrial Revolution belonging to Europe, which was about changing the means and modes of production, the term revolution is now applied to other spheres as well. No doubt the revolution that helped the nation battle hunger was a huge change from earlier agrarian practices, but was the change in scale or in the means and modes of production?

When one looks at the development of Panjab as a hub of agriculture one notices the means and modes of production in agriculture in Panjab changed not in the 1960s but much earlier — when the British created the canal colonies. What we call the Green Revolution was actually an agriculture of steroids, a boost, a creation of a factory for farm produce in which we neglected the core component — nature.

In 1879, the British constructed the Upper Bari Doab canal to draw water from the Chenab river and take it to Lyallpur (now in Pakistan and renamed Faisalabad) to set up settlements in uninhabited areas. Promising to allot free land with several amenities, the government persuaded peasants and ex-servicemen from Jalandhar, Amritsar and Hoshiarpur to settle there.

Area irrigated by canals in British India's Punjab province in 1915. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Peasants from these districts left behind land and property, settled in the new areas and toiled to make the barren land fit for cultivation. The Chunian Colony in the southern part of Lahore district with an allotted area of 103,000 acres was the next project.

Eighty per cent of the land was allotted in the form of small holdings of up to 50 acres, known as peasant grants. It was with the opening up of Chenab Colony (now in Pakistan) that agricultural colonisation assumed significant importance. This was the largest of the canal colonies, with an allotted area of over two million acres.

This habitation of Lyallpur was the original Green Revolution. As soon as the hard-working farmers had made the land fertile, the British government enacted new laws to declare itself master of this land, denying the peasants the right to ownership.

These laws reduced the peasants to sharecroppers; they could neither fell trees on these lands, nor build houses or huts or even sell or buy such land. If any farmer dared to defy the government diktat, he could be punished with eviction from the land. The new laws decreed that only the eldest son of a sharecropper was allowed to have access to the land tilled by his father.

If the eldest son died before reaching adulthood, the land would not pass to the younger son, rather it would become the property of the government. This created discontent among the peasantry and also created the undue interest in the male child that Panjab still prefers, causing a huge skew in its gender demographics from which it is only now emerging.

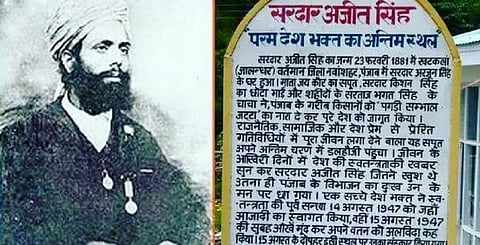

In 1907, in Lyallpur, Ajit Singh Sandhu — also Bhagat Singh’s uncle — spearheaded the movement that articulated the farmers’ discontent. In his autobiography, Ajit Singh wrote: ‘I had deliberately selected Lyallpur … because it was a newly developed area. This district had attracted people from all over Panjab and was especially populated by retired soldiers. I was of the view that these retired army personnel could facilitate a rebellion.’

Indeed, his hunch proved to be true. There was a great deal of attraction and sympathy for the Pagdi Sambhal Jatta movement within the army. The catchy slogan, Pagdi Sambhal Jatta, the name of the movement, was inspired by the song by Banke Lal, the editor of the Jang Sayal newspaper.

When a contingent of over two hundred Sikh soldiers attended a meeting in Multan, the direct fallout of this was that soldiers at many places refused to obey the British government’s orders to fire at the protestors at the peasant rallies.

Seething anger at the repression unleashed by the British government erupted in riots in Rawalpindi, Lyallpur, Gurdaspur, Lahore and many other towns and villages. The agitated protestors ransacked government buildings, post offices, banks, overturning telephone poles and pulling down telephone wires.

It was then that Lord Ibbottson, the governor of Panjab, dispatched an urgent telegraph to the viceroy, Lord Hardinge. He wrote, ‘Panjab is on the brink of a rebellion being led by Ajit Singh and his party. Arrangements must be made to halt it.’

Just prior to this, on August 29, 1906, the viceroy Lord Minto had written to the then India Minister in Britain, Lord Macaulay: ‘Ground is being prepared for a rebellion in the armed forces. Literature of a certain kind is being distributed among the soldiers and this will no doubt result in a rebellion.’

Ajit Singh’s travels through the central and western provinces of India during the massive famine of 1889-90 which left one million dead and later, during the floods and earthquakes in Srinagar and Kangra, had shaped his ideas and firmed his resolve to fight to overthrow the British.

His means went beyond the moderate Congress means of petition, prayers and protest. He believed in agitation, strikes and boycotts. In 1903, when the viceroy Lord Curzon had invited all kings and princes to declare their allegiance to the Raj, Ajit Singh and his brother Bhagat Singh’s father Kishan Singh came to Delhi. They secretly met many kings and urged them to build up another revolt on the lines of 1857. All they got were formal assurances of support but no real support.

In 1906, Ajit Singh participated in the Congress session at Calcutta, to seek out and forge links with patriots who wished to go beyond the Congress’s methods of petitioning the British rulers. Upon returning to Panjab, these patriots founded the Bharat Mata Society called ‘Mahboobane Watan’ in Urdu.

It was an underground organisation. Kishan Singh, Mahashay Ghasita Ram, Swaran Singh and Sufi Amba Prasad were some of its trusted lieutenants and active members. Their main objective was to prepare to re-enact the revolution of 1857 on its fiftieth anniversary in 1907.

In May 1907, the British police arrested Ajit Singh and another prominent leader, Lala Lajpat Rai and sent them to Mandalay. While the national leadership of the Congress threw its full might behind Lala Lajpat Rai, they maintained a complete silence on Ajit Singh.

On the ground, the Pagri Sambhal Jatta movement had spread from the peasants to the army. The government had withdrawn its laws and later returned ownership to the peasants. Considering these, they released Ajit Singh, who received a hero’s welcome in the state.

However, soon after his release, curbing his newspaper, Peshwa, the British passed another warrant with the clear intent of securing a death sentence for him when he escaped India from Karachi. He travelled to Iran, then to Europe and South America. He spent around four decades abroad.

During World War II, from the Indian soldiers fighting for the British captured by Italy, he raised a cadre of 10,000 soldiers for the Azad Hind Fauj. Yet, with Partition imminent, he was heartbroken. Keeping his frail health in view, he was sent to Dalhousie where he breathed his last on the morning of August 15, 1947 — the day India became independent.

The reason Ajit Singh Sandhu’s story is important is because it has to do with how Panjab was being turned into a British factory enterprise to export wheat for British soldiers in Europe. Another important early twentieth-century figure was Sir Chhotu Ram (1884–1945).

Born near Rohtak, in present-day Haryana, Sir Chhotu Ram’s contribution to the legal aspect of peasantry has been largely ignored. Sir Chhotu Ram resigned from the Congress in 1920. Along with Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan and Sir Fazli Husain he launched the Unionist Party to represent the interests of Panjab’s large feudal classes: landed gentry and landlords.

This was in response to the British-sponsored Panjab Land Alienation Act of 1900 which defined land ownership in terms of ‘agriculturist’ and ‘non-agriculturist’, thus affecting the moneylenders who were mostly Hindu and could no longer attach the properties of the peasants.

Though Muslims were a majority in the Unionist Party, Sikhs and Hindus also supported it. The Unionists supported the British Raj in the 1920s and 1930s. They contested elections to the Panjab Legislative Council and the Central Legislative Council when Congress and the Muslim League boycotted them.

As a result, the Unionist Party dominated the provincial legislature until India’s independence and Partition through a later pact between its leader Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan and the Muslim League leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

The Radcliffe Line divided more than a region; it also obliterated the challenge to Congress that existed in Panjab since most Unionist leaders belonged to, and their landholdings lay in, what became Pakistan.

Sir Chhotu Ram, as revenue minister of Panjab, enacted a number of laws to regulate the agrarian sector. Among them was the Restitution of Mortgaged Land Act, 1938. It terminated all old mortgages existing before the Panjab Alienation of Land Act.

It offered statutory extinguishment of mortgage of agricultural land, after the mortgagor had paid an amount twice or more of the principal amount. This law helped to restore almost 83,500 acres of agricultural land to almost three lakh sixty five thousand poor peasants taken over by moneylenders using earlier laws.

Another law, the Registration of Moneylenders Act, made it mandatory for a moneylender to obtain a licence before doing business. Conciliation Boards were set up and the majority of its members were farmers. The Agricultural Produce Marketing Act shifted the grain market from the control of moneylenders by forcing them to get registered.

The registration of mandis began by the formation of Mandi Regulation Committees, with two-thirds of the representatives having to come from the farmers and one-third from moneylenders. These laws favoured the farmers over the moneylenders and went a long way in regulating the procurement and marketing of agricultural produce.

Another significant law was the Relief of Indebtedness Act, 1934, which offered settlement between the debtor and creditor through debt conciliation boards, which were quasi-judicial bodies.

The Debtors Protection Act, 1936, was a law under which the decree holders (the person who has a court order to take over / sell off somebody’s property as mentioned in the court order, for the debt / recoverable dues from that person), the majority of which were moneylenders, were restrained from taking over or selling off the essentials of the peasants and farmers. For example, house, fodder, standing crop, bullock cart, milch cattle, cow shed.

Clearly, the 2016 Rural Indebtedness Bill owed a lot to Sir Chhotu Ram’s laws but sadly did not improve upon them.

Between Sir Chhotu Ram’s time and now, the Panjab Agricultural Indebtedness (Relief) Act, 1975, was the only other law which addressed this issue by providing for discharge of the debt of farmers and release of mortgaged property if a sum exceeding or equivalent to one and a half times of the principal amount of the debt had been paid.

This Act was never implemented. Clearly, Panjab’s pagdi (the turban), the symbol of its dignity, has not been steady on its head for over a century now.