Copyright legacy of the great

January is a bleak month in Delhi. At least for some of us. There is the damp, grey and foggy weather, for one, and for another, the memory of the cold-blooded assassination of a revered figure that hangs over the city. It is a memory that still haunts the nation, increasingly faintly, perhaps, as it pulses to a new beat. The Republic Day celebrations that overshadow all else in this month are held not far from where Mahatma Gandhi was shot dead by a right-wing Hindu fanatic on January 30, 1948, for trying to heal the bleeding wounds of a nation torn apart. That was less than six months after he had brought independence to India.

Searching for Gandhi’s last speeches as he embarked on his final fast in Birla House (now Gandhi Smriti) to end the communal bloodletting in the capital, I was able to quickly to find what I wanted on the internet. The talks that Gandhi gave at the daily prayer meetings he held at Birla House hold vitally needed messages on decency, humanitarian values and secularism even now. But this column is not about the sage advice he gave his violence-prone countrymen 76 years ago; it is about the ease with which one is able to lay one’s hands on his writings and speeches books if only we wanted to understand our freedom struggle, Partition-related history and ourselves.

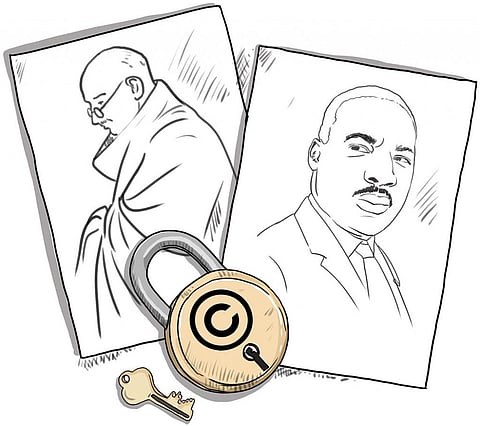

The focus here is on the copyright law and its impact on the works of two great men in different countries and of different generations: Gandhi and US civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King Jr, who fought for the rights of African Americans. There were strong links between the two. King was deeply influenced by Gandhi’s non-violent struggle against forces of oppression and hate, calling him the guiding light of his technique of social change. Sadly, the other similarity is tragic. The Black rights leader was also assassinated, five years after he made the momentous “I have a dream” speech during the March on Washington in 1963. There is a January link here, too, as the US commemorates January 15, his birthday, as Martin Luther King Jr Day.

There is, however, a sharp divergence in the way the two iconic leaders dealt with copyright. Gandhi, being a lawyer, had clear understanding of the abstractions of the copyright law, but he applied a contextual frame to this understanding to arrive at a practical solution to how it affected his works as a writer and publisher. It is a subject that has been rarely highlighted, much less researched. The exception is Shyamkrishna Balganesh of the Columbia Law School, who has written an absorbing research paper on this rather recondite aspect titled Gandhi and Copyright Pragmatism. The development of Gandhi’s views on copyright, says Balganesh, shows that he anticipated several of today’s critical debates on copyright concerns and developed what he describes as “copyright pragmatism.” This means engaging critically with what copyright laws prescribe but also keeping in mind how it works contextually by weighing the various costs and benefits.

Gandhi’s initial stand on copyrighting his works was a firm rejection. In 1926, Gandhi began publishing instalments of his autobiography, titled The Story of My Experiments with Truth, in two journals that he edited: Navjivan, which was in his native Gujarati language and featured the original chapters; and Young India, which ran the English translations of the work. Gandhi’s autobiography was hugely popular with readers, and he allowed other newspapers to reproduce the chapters without his permission. Although his supporters advised Gandhi to exercise his copyright to stop the exploitation by commercial newspapers, he was dead set against the idea. “Writings in the journals which I have the privilege of editing must be common property. Copyright is not a natural thing. It is a modern institution, perhaps desirable to a certain extent. But I have no wish to inflate the circulation of Young India or Navjivan by forbidding newspapers to copy the chapters of the autobiography.”

Gradually, though, Gandhi was forced to acknowledge the value of copyright, starting with the time when the US publisher of his autobiography, Macmillan, demanded that he assign all rights in the work to the publisher. In order to do so, Gandhi had to first assert and claim them under copyright law, which was against his principles. But he yielded because “I felt that there might be no harm in my getting money for the copyright and using it for the charkha propaganda or the uplift of the suppressed classes.” And there was also the added advantage of his message reaching a wider public through a well-known publisher.

Eventually, Gandhi bequeathed the copyright in his works, comprising thousands of articles and several books of which the autobiography is a bestseller, to a trust that he had helped establish, the Navjivan Trust. In 2009, some 60 years after the death of Gandhi, the works came into the public domain despite a strong campaign by Gandhi scholars that Navjivan should retain it. Their argument was that once such works came into the public domain, commercial entities would profiteer from them and not maintain their purity. A similar ruckus erupted in 2001, when Visva Bharati University lost the copyright on Rabindranath Tagore’s works and sought an extension of 10 years. At the time, the government said that it had to keep the public interest in mind since the advantages of putting the works in the public domain outweighed those of keeping the rights with the university.

In the case of King, public access has not mattered so far in a copyright battle that has turned ugly. His epochal I have a dream speech is not in the public domain as the copyright continues to be with his estate, which enforces it strictly and seeks extortionate fees for licensing it. King took out a copyright on the speech in 1963, and under US law, what was then a 56-year copyright has been turned into a 95-year run. This is a pity, because it means the American public seldom sees more than snippets of one of the most significant speeches in its history. Experts point out that this has undermined the fair use doctrine because even those users that might have a plausible right under this rule have either dropped their plans or been forced to pay stiff licence fees to the King Estate or the commercial entity with which they have tied up.

What a tragedy this. Visionary leaders such as Gandhi and King belong to the ages and so do their works.

This was first published in the 1-15 February, 2024 print edition of Down To Earth