Quest for Modern Assam: The vast canvas of a small state and its struggle for identity and modernity

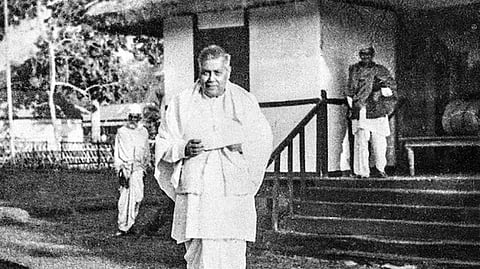

Assam's first Chief Minister, Gopinath Bardoloi. Photo from Sanjoy Hazarika's book, 'Strangers of the Mist'. Permission for reuse from author

Arupjyoti Saikia is undoubtedly contemporary Assam’s finest historian and, by that measure, one of India’s most accomplished. He does not believe in half measures or over-reliance on the writings of others, no matter how reliable. Saikia does not make facile assumptions or turn to the net every time there’s a question to be answered, a fact to be checked.

He dives deep into archives and libraries, both in Assam as well as Delhi, London and Yale, scouring for evidence and documentation. He asks uncomfortable questions and pays attention to detail, the hallmark of a seeker of inconvenient truths. As in all his earlier large and wide-ranging books, which look at peasant challenges in Assam (A Century of Protests), preceded by Forests and Ecological History of Assam and more recently his biblical sweep of the Brahmaputra, The Unquiet River, spread over 583 pages, illustrated with photos as well as old and new maps.

Saikia’s Quest for Modern Assam does not disappoint. Its size and scope are daunting: it spans 58 years and 832 pages, of which 298 pages comprising Bibliography, Timeline and references, giving readers an understanding of the attention which he pays to detail. His major works have been focused on his home state of Assam where he is a professor of history at the Indian Institute of Technology at Guwahati, located very close to the Brahmaputra.

Saikia brings a consistent scholarship to his telling of tales. He avoids jargon and the haste with which some new self-styled historians of the state and the region have rushed into print with breathless haste. His formidable tome acknowledges the challenges in writing “complex biographies of Indian states in the post-colonial period” and points out the need for the passage of time to reflect not just on events but also the development of historical processes, trends and circumstances, political, economic and environmental. Access to archival material is crucial.

The pace is set with the opening — and this is where the historian shows nuance, clarity and wit. With a panoramic sweep that connects all the loose ends — ethnicity, agrarian distress, environment and political conflict and the lives of people and communities, Saikia weaves a rich and detailed tapestry. Thus, we start with the end years of the Second World War, where Japanese military inroads showed up Assam’s vulnerability and the fallacy of believing in the seeming fortresses of the eastern hills. Saikia skillfully merges the many events which developed parallel to each other in those critical years before India’s independence, underlining what he described as An Empire in Disarray where a range of issues tested the mettle of the colonial rulers as well as the local political leaders. These included the extensive migration of lakhs of distressed rural Bengali peasants into parts of western Assam, drawn by the new land policies of the Muslim League government in Assam and pushed to desperation by the horror of the Bengal famine of 1943-44 which killed no less than three million persons. Parallel to this ran the wartime Allied effort to build a major supply and forward base to deal with the Burma and China fronts, through air, on food, truck and train with oil pipeline being placed over hundreds of kilometers to ensure reliable and sustained fuel supply apart from the blazing battles of Kohima and Imphal which spanned a huge area, causing displacement and devastating forests and wildlife.

The Quit India movement stressed a colonial government already under huge pressures of security and logistics in the midst of a war. All this was made complicated by the emergence of not less than four plans by British officials to carve a Crown Colony out of the hills of the region of the Northeast and join them to the Burmese highlands even as India marched to freedom, with hiccups coming along during negotiations with the Nagas who sought to remain independent and the Partition.

There is a lovely vignette of Parnkanta Buragohain, an Assamese trader who had lived in Rangoon (now Yangon) for several years before leaving along with other refugees fleeing the advance of the Japanese. The enterprising Buragohain, who kept a meticulous diary, traveled through forests and hidden pathways on elephant back. He undertook a long journey with the help of ethnic groups with whose languages and food he was familiar.

While the Bardoloi Sub-Committee Report’s recommendations for special Constitutional protection for tribal communities in the region through the Sixth Schedule has been covered extensively in other books and studies by anthropologists, sociologists and historians, Saikia also reviews the impact of demands at that time by Assamese nationalist politicians who favoured strong and autonomous states which could stand up to an overwhelmingly powerful Centre.

This tussle over the idea of a federate polity — or Union of states — and the need to balance the powers of the Centre and even rein them in has resonated though India’s post-independence journey. It remains unresolved with strong voices from the increasingly affluent states of Southern India demanding a greater role in financial power sharing. They cite their contribution to the national exchequer and criticise the fact that the Centre apportions more funds to poorer states like Uttar Pradesh.

Saikia quotes Kuladhar Chaliha, a prominent Congressman, “You seem to think that all the best qualities are possessed by people here at the Centre. But the provinces charge you with taking too much power and reducing them to a municipal body.” This very heated debate continues, irrespective of which political party is in power at the Centre.

Indeed, the book points out how Assam, despite all the pressures that it faced, remained among the top states as far as Net Domestic Product (NDP) was concerned, as a result of pre-independence capital investments, but began sliding after the mid-1960s, with poor health, nutrition and income among significant numbers of the population. The slide became a precipitous fall after the growth of strident regionalist tendencies, continuing poverty and poor HDI, fragmented infrastructure as well as lack of resource mobilisation. It was now till about the first decade of this century that Assam could be said to have begun to turn the corner.

Deftly, Saikia traverses the complex road of language politics, which has been at the heart of identity mobilisation in Assam and the struggle by its founders, scholars and cultural icons, to tackle some of the bitter prejudices which have remained. While dwelling on the continuing challenges of unemployment, he also looks at efforts to shape the state as a modern entity with a focus on institutions and the sinews of government. Given his previous work, it is but natural that landlessness, agrarian penury as well as the constant battle between ‘development’/infrastructure growth and the loss of forests and habitat and the challenges facing poor peasants and the flood plains find major space in his book.

Saikia’s books and chapters are ambitiously voluminous but very readable. In sweeping strokes, he paints the rise of the Naga movement for independence, boundary disputes, the resistance to the imposition of Assamese in what is today’s Meghalaya, and resentment in other tribal communities leading to demands for separate homelands. The rise of the All-Assam Students Union (AASU) and regionalism, the growing communalisation of politics and the influx of refugees from Bangladesh in 1970-71 is another part of the canvas. So are the questions of irregular migration and the “anti-foreigner” movement which resulted in numerous horrendous killings including the Nellie massacre. He gives space and time to the role of the United Liberation Front of Asom. While none of this may break new ground, Saikia approaches the range of issues with a felicity of information and a masterly touch, with sympathy and compassion, while relying on facts and records.

There are different dimensions to the Assam story, providing clear delineation and prioritising areas of concern. For ultimately, a historical survey of this scale cannot cover everything. The author has the right to choose which in his/her view has greater relevance and priority. It is a choice driven by both professional and personal approaches.

Thus, while Saikia looks at the role of women in different fields, he also views the formal recognition of the Sattriya dance as a classical dance form of India by the Centre as bringing “some of the social recognition sought by the Assamese middle classes and also significantly contributed to the consolidation of Assamese nationalism, which is increasingly projected and interlinked through Vaishnavism.”

In this aspect, he pays tribute to abbots of the Vaishnav monasteries and the great scholar Maheswar Neog who battled for decades to get formal recognition for Sattriya. Dr Bhupen Hazarika, himself a great cultural icon and then head of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, enabled the decision nearly half a century later.

Arupyoti Saikia has provided us with an encyclopedic book, rich in grounded knowledge and content, with an unerring perspective with a sharply focused lens on a land, its people and their challenges. In the space of just over half a century, it covers the breathless changes that have raced through Assam and asks key questions at the end.

One of these is the poignant one whether Assam can “escape from the burden of economic deprivation without causing distress to her environment?” The ongoing destruction of wetlands, other habitat, forests and even magnificent trees along its highways which provided protection and shelter to many species, not just humans, is a reminder that Saikia, with his formidable understanding ecological spaces, is not just asking a question. In the question lies a statement of fact, if not an answer.

A magisterial work as this deserves another — it is strongly recommended that another major study be taken up some years down the line to review Assam’s critical years between 2000-2025, a time of many transformations, for good and otherwise.