Climate change may have led to the complete colonisation of Polynesia by indigenous Polynesians, a new study has found.

The researchers from the University of Southampton and University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom found that a major shift in South Pacific climate conditions—beginning around 1,000 years ago—may have pushed people to settle further east and move away from increasingly drier conditions in the west.

Samoa and Tongo, islands in western Polynesia were already settled. But as they became drier, more eastern islands like French Polynesia (Tahiti), which were wetter, became more attractive for colonisation.

The study, part of a wider project between Southampton and East Anglia called PROMS (Pacific Rainfall over Millennial Timescales), examines this shift and its likely impact on migration.

According to a statement by the University of Southampton, the team of researchers “collected sediment cores on the islands of Tahiti and Nuku Hiva in Eastern Polynesia to analyse plant waxes — fatty layers left on leaves. World-leading laboratory analysis of these plant waxes reveals how wet or dry the climate was when the leaves grew. The team combined these new records with other records from across Polynesia, in the Pacific”.

Then, they estimated how rainfall had changed across the Pacific during the last 1,500 years. With new climate model simulations, the team were able to uncover when and where this climatic shift in rainfall occurred, and what probably caused it.

According to them, the most likely cause is a natural change in the pattern of sea surface temperatures across the Pacific which drove an eastward shift of the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ) between approximately 1,100 and 400 years ago.

“The SPCZ is one of the biggest features in the global climate system, a region of high rainfall stretching over 7,000 km from Papua New Guinea to beyond the Cook Islands. The climate shift identified in this new study saw the western part of this rain band become progressively drier, and its eastern part wetter,” the statement by the University of Southampton said.

This long-term drying of western areas could have acted as a ‘push’ for migration, while the increase in rainfall and freshwater availability in the east may have served as a ‘pull’ to settle new islands.

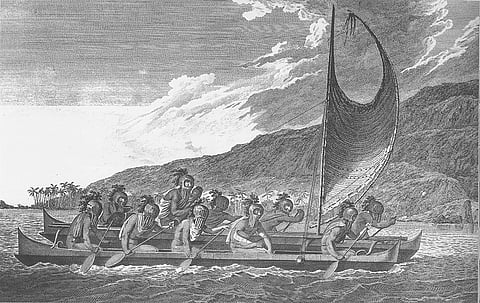

“It’s possible the climate shift acted as a driver for people, encouraging them to sail progressively east to islands such as the Cooks and Tahiti,” the statement noted.

“Water is essential for people’s survival, for drinking and successful agriculture. If this vital natural resource was running low, it’s logical that over time the population would follow it and colonise in areas with more reliable water security – even if this meant adventurous journeys across the ocean,” the statement quoted co-lead author on the paper, Mark Peaple of the University of Southampton.

Ocean variability drives a millennial-scale shift in South Pacific hydroclimate has been published in the journal Nature: Communications Earth and Environment.