It dampened the spirit of electric vehicle (EV) enthusiasts when the Union Minister of State for Heavy Industry and Public Enterprises, Babul Supriyo, informed Parliament in January this year that the government has no plans to make all vehicles powered by electricity by 2030. He did not share the enthusiasm of his colleagues—former Union power minister Piyush Goel, who in April 2017 had aimed for 100 per cent electrification by 2030, and the Union transport Minister Nitin Gadkari, who at the annual convention of the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM) in September 2017 said that all fossil fuel vehicles would be pushed out by 2030 to promote electric mobility. Clearly, there is lot of hype and hope around electric mobility today but no clarity how to get there.

Though India is highly unlikely to meet the National Electric Mobility Mission Plan target of having 6-7 million electric vehicles by 2020, the government is making optimistic plans. The Cabinet has approved a mission on electric mobility to be led by the NITI Aayog. The Union government’s scheme, Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicle (FAME), launched in 2015, is under revision to link electro-mobility with public transport strategy. The Union Ministry of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises is supporting electric vehicle-based public transport in Delhi, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Bengaluru, Jaipur, Lucknow, Hyderabad, Indore, Kolkata, Guwahati and Srinagar. Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL), a joint venture company of public sector undertakings, is procuring 10,000 electric vehicles for government agencies from manufacturers in India.

This buzz has provoked SIAM to issue a white paper with a roadmap stating 40 per cent EV sales is possible by 2030 while aiming for a complete shift to EVs by 2047. But all are not convinced. Mercedes-Benz India is reported to have urged the government not to rush with the all EV push and foreclose better technology options. Toyota is reported to have said that an 100 per cent electric fleet by 2030 is not practical and is not the way forward. The Automotive Component Manufacturers Association of India has asked for a slow down.

Despite this scepticism, nearly all auto companies are building their EV portfolio. Though the current sales volume of EV is too low to excite or convince, the direction of change is certain. The Vahan Dashboard website of the Union Ministry of Road Transport and Highways shows that though battery-operated EVs (these are zero emission vehicles, or ZEVs) were 0.05 per cent of the new vehicle sales in 2015, between 2015 and 2017, the total sale of all EVs, including hybrids, saw an impressive seven-fold increase—from 10,321 in 2015 to 72,482 in 2017 (see ‘On right track’,). One-third of these were sold in Delhi.

Curiously, while established auto companies are warming up slowly to the idea of EV transition, lesser known entities, including watchmakers like Ajanta and start-ups, are stoking the change. India’s earliest electric car, Reva, was incubated in Chetan Maini’s start-up in the mid 1990s before reaching the assembly line of the Mahindras (see ‘Who are making EVs in India today’,). It continues to be India’s only affordable ZEV.

A DISRUPTION

These are the exciting and disruptive times in India. Replacing the deeply entrenched internal combustion engines (IC) with electric drive train is transformative. The most unexpected and early disruption came around 2012 from the informally made battery-operated E-rickshaws. These affordable ZEVs of the masses destabilised the auto rickshaws of original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). India is currently estimated to have 0.4 million electric two-wheelers and 0.1 million E-rickshaws, and only a few thousand electric cars. According to an October 2017 forecast of the EREP Market Research Series, of the total estimated future electric fleet size if represented as total battery storage capacity, the overall EV market for battery storage in India is likely to be 4.7 GW in 2022, and over 60 per cent of this capacity will be driven by E-rickshaws batteries. Such spontaneous change of such scale in the informal market is unknown in the advanced markets.

The Indian auto industry cannot ignore the early signs any more. Among car manufacturers, Mahindra already has electric variants in hatchback, sedan, light commercial van and SUV. Maruti Suzuki will have a joint venture with Toyota to produce small electric cars. Hyundai is developing all electric passenger cars; Renault is bringing out its popular hatchback in electric; Honda, that expects EVs to be 65 per cent of its car sales by 2030, plans to set up a lithium ion battery manufacturing facility in India; Nissan will launch its electric hatchback in 2018; Mercedes-Benz will bring electric cars from its global line up by 2020; Volkswagen, Volvo and Audi have announced electric variants; and, Tesla will also come to India.

| Why zero emissions vehicles make sense in India?

India IS desperate to curb air pollution, strengthen energy security and mitigate climate impacts. Electric vehicles (EVs) provide these co-benefits. Official estimates show that India with ambitious EVs can save about 64 per cent of energy demand for road transport, 37 per cent of carbon emissions by 2030 and save $60 billion in diesel and petrol costs by 2030. An initiative by the NITI Aayog, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry and Rocky Mountain Institute estimates that with 100 per cent electrification, India can save R20 lakh crore and 1 gigatonne of CO2 emissions. |

Several electric two-wheeler producers including Hero Electric, Lohia Auto, Electrotherm, Avon, Indus, Tork Motorcycle and Ather Energy, are already selling. Honda, Bajaj Auto Ltd and TVS are promising new products by 2020. But electric two-wheeler sales have not picked up to the desired extent in India. Most models do not measure up to consumer expectation of power and performance. A total of 19 of the 24 two-wheeler models in the market are low speed scooters, with a maximum speed of 25 km/hour and maximum power output of less than 250 watts.

In the heavy duty segment, BYD China has launched E-buses in India. Daimler, Volvo, Sia, Mann and Navistar are in advanced stages of testing prototypes and have targeted to launch in India in 2020. Ashok Leyland and Tata Motors are also working on their prototypes. What path will India follow to allow prototypes to jump start to commercial scale?

Will India move predominantly to fully battery-operated electric vehicles or also adopt hybrids, which are a combination of internal combustion engines and electric drive? The Union government’s policy tilt is quite clear from Down To Earth’s conversations with officials of the Union Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, the Ministry of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises, and from the policy documents of the NITI Aayog. India will be on full electric pathway and not get distracted by the hybrids.

Hybridisation is an intermediate strategy for improving fuel economy. While battery-operated vehicles run entirely on electricity (with zero tailpipe emissions), fully hybrid vehicles (hybrid vehicles are of three kinds—mild hybrid, strong/full hybrid, plug-in hybrid—depending on the extent of utilisation of electric propulsion) can be driven on electric mode for some time but have less range (distance they can travel on electricity) than pure battery EVs, use combustion and pollute. Ashok Jhunjhunwala, professor at IIT-Madras and advisor to the Government of India on EV strategy, says, “Hybrids do not get us to anywhere because it is a pretty old technology. Incentivising hybrids will hurt EV. We will get lost in hybrids and the world will move over to EV and then we will be importing EV technology.”

India has already burnt its fingers with a misplaced policy to incentivise diesel mild hybrids under the FAME programme. A study by Delhi-based non-profit Centre for Science and Environment shows that since the beginning of FAME, of the total end-user subsidy given, 63 per cent has gone to diesel mild hybrids, 9 per cent to strong hybrids, 10 per cent to electric four-wheelers and 18 per cent to electric two-wheelers. Diesel mild hybrids are only 7-15 per cent more fuel-efficient than comparable conventional diesel models. This forgoes the benefits of improving fuel efficiency that can be as high as 32 per cent in the case of plug-in-hybrid cars and 68 per cent for fully electric models.

This loophole, under which mild hybrids were cornering a majority of the EV subsidies, was plugged when the Ministry of Heavy Industry and Public Enterprises issued a notification on March 30, 2017, to disqualify mild diesel hybrids from FAME. Officially, mild hybrids are defined as “those that have minimal application of electric energy and use regenerative braking power only to assist the motor to start from the stationary position”. These vehicles cannot run on electric power alone. A strong hybrid vehicle has a rechargeable energy storage system and with an electric drive train allows more significant fuel and emissions saving. Plug-in hybrids have a provision for off-vehicle charging but are not available in India. Fully battery-operated EVs are powered exclusively by an electric motor for full driving range and have zero tailpipe emissions.

Makers of strong hybrids are, however, worried. Though they are enjoying FAME incentives as well as extra points for calculation of corporate average fuel economy (it is the average economy across all car models that a manufacturer makes. For example, if a company makes a fuel-guzzling sports car, it will also have to make an ultra-efficient car) for compliance with the fuel economy standards, these cars have become more expensive under the GST regime. These cars are bracketed under luxury product that attracts 43 per cent tax. In Delhi, this has increased tax burden on Toyota Camry and Toyota Prius, the only two strong hybrids, by 22.4 per cent from pre-GST times. According to the data shared by Toyota, their total national sales have dropped by as much as 78 per cent. This has raised questions about tax incentive for hybrids.

Globally strong hybrids, especially plug-in hybrids, enjoy incentives but not as much as fully electric vehicles. Lew Fulton, formerly with the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA), says, “The governments should incentivise hybrids correctly based on fuel economy level of models. But make sure they do not incentivise the sale of large cars over smaller cars and pure electric. As batteries and EVs become cheaper, maybe hybrids will not matter as much, though plug-in hybrids can play an important role.” Strong hybrids are in the large car segment.

Data speaks. The reported fuel economy of Toyota Camry hybrid, a large car, is 19.16 kmpl, which is substantially better than that of regular Camry (12.98 kmpl). The fuel economy of Toyota Prius is 26.27 kmpl. Thus hybrid versions have better fuel economy than its peers in the same size class. But a small car, such as Maruti Suzuki Dzire (ZXI Plus AGS) with smaller engine capacity has mileage of 22 kmpl, better than hybrids. Another small car, Maruti Alto K10 LX (Petrol) has a mileage of 24.07 kmpl. It, therefore, makes sense to transparently link incentives with performance standards to maximise fuel economy gains. For hybrids and non-EV models to qualify for tax incentive a performance target of about 20-25 per cent improvement over the fuel economy standard line of 2022 may be considered.

IS ELECTRIC INEVITABLE?

Doubters ask if it is too early for India to consider full-fledged electric pathway. The auto industry and automotive component manufacturers complain that full electric strategy will be disruptive, cause job loss and has no relevance when India is moving fast to adopt the much cleaner Bharat Stage VI (BSVI) emissions standards in 2020.

But they are missing the big picture. The global shift towards electro-mobility will be faster to drastically cut carbon emissions and public health risks, and that will change the business landscape dramatically for all. The laggards will lose out. Says Michael Walsh, former head of the motor vehicle division of the US Environment Protection Agency and advisor to the Chinese government, “As we continue our global march toward two billion vehicles, it is incontrovertible that the global fleet has to be rapidly weaned off fossil fuels. A clear pathway to a low carbon future is electric drive with renewable fuels as the source.”

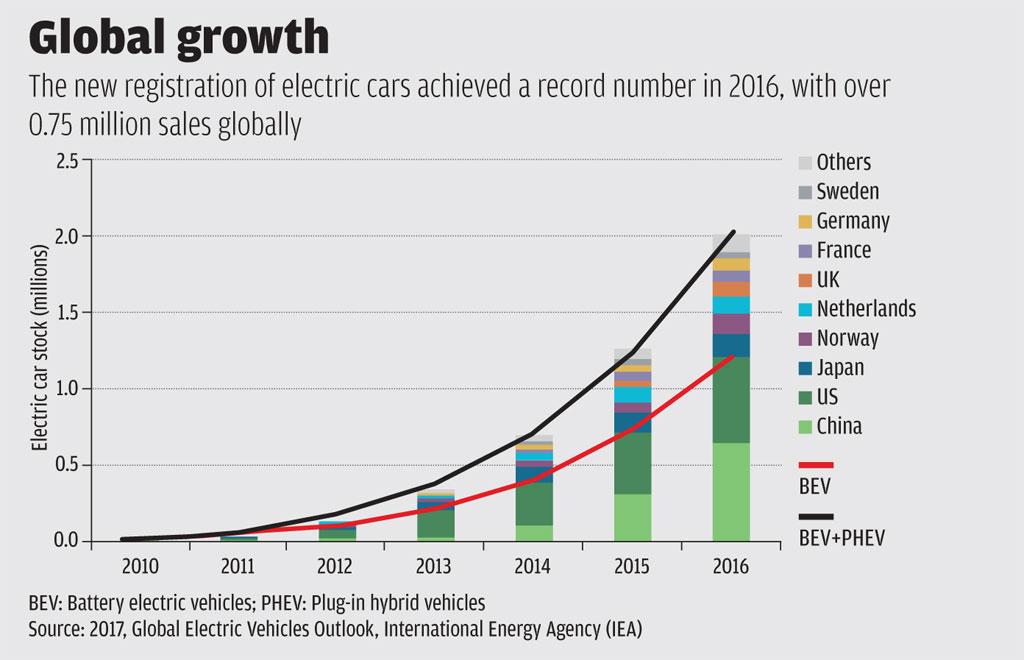

India cannot stand isolated and miss the bus. According to the Global Electric Vehicles Outlook report released by IEA in 2017, the global electric car stock surpassed 2 million vehicles in 2016 after crossing the 1 million threshold in 2015. The new registration of electric cars achieved a record number in 2016, with over 0.75 million sales globally. Stronger trends are in national markets. In Norway in 2016 about 29 per cent of new car sales were EVs; followed by the Netherlands (6.4 per cent) and Sweden (3.4 per cent). But the most dramatic shift has happened in China with more than 40 per cent of the total global EV sales, more than double of the sales in the US. This has shaken the auto world. China did it with its deliberate industrial policy of Make in China. Jianhua Chen of Energy Foundation, a Beijing-based think tank, told Down To Earth, “Made in China 2025 strategy was enacted in 2015 to encourage domestic development of energy saving vehicles and new energy vehicles. State Council [the supreme governing body of China] set target to reduce CO2 emissions from passenger and freight transport. New technical roadmap has sought 7 per cent market penetration of new energy vehicles by 2020.”

China has taken strategic advantage of local availability of raw material like lithium for battery production and expanded battery production to serve not only its large domestic market but also the export market. China’s policy has already made its EV and battery industries highly competitive and its electric buses dominate globally. This has given China a head start to find its place in the global market. The strong gravitational pull of China’s big and growing market is changing the geopolitics of global auto market. The global industry wants a pie in rapidly growing Chinese market and cannot ignore this trend.

What customers and dealers think?

LOW DEMAND: According to Rahul Mehndiratta, sales executive for the e2O Plus at a Mahindra outlet in Badarpur, Delhi, he is able to sell 1-2 e2O Plus cars a month even when around 40 potential customers walk in every month. Some government offices and taxi fleets are also buying them as part of a localised pick up and drop service, adds Mehndiratta. RANGE DOES NOT MATCH EXPECTATIONS: Subal Jalan of the Jalan Transport Private Limited, an Uttar Pradesh-based transport company, who bought an e2O Plus for commercial taxi use was disappointed as he expected his expensive variant to give higher mileage than 120 km on a single charge. He also wants more charging facilities. Charging is also a problem in high-rise buildings. WANT HASSLE FREE SUBSIDY: Rajnish Rastogi bought Ridge, a scooter made by Okinawa. But says availing subsidy should be made far easier for consumers and the range of the subsidy should also increase. REMOVE TAXES: Subal Jalan wants commercial taxes and registration fees to be removed. There is also no resale value for EVs. WORRIES OVER BATTERY COST AND SLOW CHARGING: Two-wheelers have lead acid battery that takes longer to charge—8-9 hours. It also costs around R22,000 and has a warranty of only one year. Customers want shorter charging time and longer warranty period. Sunil Saini of Mahindra showroom says, "Battery swapping would reduce the initial price tag and do away with the difficulties of self charging." |

Yet another big push for electric mobility in the global market is coming from the backlash against diesel in major markets after the dieselgate (see “Faux Wagon”, Down To Earth, 16-31 October, 2015). Diesel cars were expected to play an important role in meeting the efficiency targets in Europe. “But dieselgate has made it clear that the very sophisticated modern vehicles with advanced electronic controls present very difficult challenges regarding real world in use compliance with emissions standards,”says Walsh.

As European cities, including London, Paris, Oslo, Munich, Stuttgart and Madrid, are restricting diesel cars, the EV strategy is picking up. More so because IC engines under Euro VI have to pass very exacting real world emissions tests. Sales of diesel cars have crashed in the UK and dropped even in Germany. EV sales have picked up in the UK. Some global car companies, including scandal-tainted Volkswagen, are now questioning the wisdom of diesel subsidy in Europe. Dorothee Saar, policy analyst from Berlin-based non-profit Deutsche Umwelthilfe, told Down To Earth, “Incentives for new technologies in Germany include pure electric vehicles and hybrids as local authorities, as in Berlin, replace diesel to improve air quality.”

The writing on the wall is clear. It is becoming increasingly difficult, complex and expensive for IC engines to comply with tighter emissions standards, more complex test procedures, as well as significantly tighter targets for fuel economy and heat trapping CO2 emissions. The US Tier III standards and upcoming Euro VII standards will severely challenge IC engines. In the European Union, for instance, the average CO2 emissions for new cars in 2030 will have to be 30 per cent lower than the 2021 target of 95 g of CO2 per km which is similar to small carbon footprint of two-wheelers. These developments are making electro-mobility attractive and inevitable.

(This cover story was first published in the 1-15th issue of Down To Earth).

As India is struggling to roll out its EV roadmap, it has to understand the global strategies that have worked or failed. The lessons come from the major EV markets of California, China and Scandinavian countries that have adopted regulatory mandates and incentives to promote EVs.

California was the first to adopt ZEV mandate in the 1990s that says a specified percentage of total cars sold by each manufacturer must be ZEVS. This mandate has evolved over time. Melanie Zausche of California Air Resources Board (CARB), the apex air pollution monitoring agency of California, told Down To Earth that now the ZEV regulation sets vehicle credit requirements for ZEVs expressed as a percentage of annual total vehicles sales in California. 2025 onwards, the total ZEV per cent requirement for large volume manufacturers is 22 per cent, while the minimum pure ZEV requirement is 16 per cent.

They follow the good practice of linking incentives with performance. 2018 onwards, there is no corporate tax rebate for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) with an all-electric range of less than 10 miles (1 mile equals 1.6 km). For PHEVs with an all-electric range of 10-80 miles, the tax rebate is calculated on the basis of the available range. ZEVs with fewer than 50 miles all-electric range receive no tax rebate. Rebate is also given to the end user on the purchase or lease of these vehicles. Bart Croes of CARB told Down To Earth that even the California experience shows that “low awareness and poor knowledge of zero-emission vehicles are significant barriers to adoption. But consumers with greater awareness and experience with these vehicles are more likely to value them positively”.

California also provides non-fiscal incentives that include carpool stickers to ZEVs to use high occupancy lane. California also installs public electric vehicle charging stations, requires new construction to have a minimum threshold of EV-capable parking lots, requires state fleets to have at least 10 per cent ZEVs and is also developing a ZEV programme for medium- and heavy-duty vehicles. California is also moving one step ahead to bring a new bill to stop IC engines in the state by 2040.

Nine other US states (Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Vermont) are participating in California’s programme. Margo Oge, former environmental regulator and the director of the US government Office of Transportation and Air Quality, told Down To Earth, “Even though the Trump Administration is trying to relax the 2025 fuel economy target in the US, and even if this happens, a dozen of other states have already adopted the California clean car programme. This is a big problem for car companies as these states account for 35 per cent of the US auto market.” Also, American companies have huge international markets and cannot ignore the developments in the Chinese EV market. In fact, China is already General Motor’s largest market, she adds.

China, on the other hand, has used a combination of regulatory mandate and incentives very effectively. Jianhua Chen told Down To Earth that China’s ZEV mandate requires every vehicle manufacturer or importer with annual sales above 30,000 to sell enough new energy vehicles to generate credits equivalent to 10-12 per cent of the sales in 2019-20 and ramp up the target to 20 per cent by 2025. In 2016, vehicle sales in China crossed 28 million, so these percentages are significant.

China provides generous incentives including national subsidies, tax exemptions and charging infrastructure awards. The local, provincial and municipal governments can also provide matching incentives. Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou provide non-fiscal incentives, like exempting EVs from traffic restrictions, or fix and allow more licence plates for electric cars under the vehicle auction and quota schemes. These are the top drivers of the EV market. Moreover, China is promoting EV-based bus transport. The city of Schenzen has close to 17,000 electric buses.

The world is simultaneously realising that there are limits to incentives. Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands have turned their market around with hefty subsidies, tax breaks, nation-wide charging stations and incentives such as lower parking rates, use of bus lanes and exemption from road tax. Norway’s EV and hybrid sales in 2017 crossed 39 per cent of the new car sale. Some estimates put the figure at 53 per cent.

With the expansion of the EV market, as seen in the Scandinavian countries, the governments are finding it difficult to maintain the subsidies and are considering withdrawing or lowering subsidies. Even China was in a dilemma over extension of some of its incentives beyond 2018 though it has now extended them till 2020.

Explains Anup Bandivadekar of International Council on Clean Transportation, an international non-profit, “The only reason everyone is considering withdrawing EV incentives is because the subsidies do indeed add up to substantial sums as the volume picks up.

Norway appears to be one of those places where the tipping point has been reached. But in other places, especially where the EV sales share is still in low single digits, withdrawing subsidies hastily is likely to cause the EV sales growth to slow down.”

If the fiscal incentives are phased out, EVs must be supported by a number of complementary, albeit non-fiscal incentives. “Over a somewhat longer term we would need regulatory measures including mandates to see markets are reaching a tipping point,” adds Bandivadekar.

INDIA MUST CHART NEW PATH

As the policy targets for EVs begin to get more ambitious in India, the automobile industry asks for a clear roadmap. “While the move to electric vehicles is inevitable, a clear policy outline from the government is necessary,” says Sumit Sawhney, managing director, Renault India.

Indian officials admit that the EV strategy will need demand incentives, subsidies and regulatory mandate. But there are questions about India’s capability to provide enormous support to build its market, like China has. Yet without support India cannot build market or be globally competitive in the EV market and will be left behind. This has created a strong interest in finding the right balance between providing strategic support and making the market work for scale and affordability.

Jhunjhunwala says India will have to innovate and do things differently. “India should build its EV industry even if there is limited or no subsidy. It can use its potentially large market and large public fleets to get there.”

Link EV strategy with public transport: India’s pathway to electric mobility will be different from advanced markets that are car-centric. India’s win-win strategy will come from incentives and subsidies linked with EV-based public transport—buses, para transit, feeders to metro, shared mobility, school buses and large fleet of delivery vehicles. Additionally, two-wheelers, a very polluting segment, are yet another target of large-scale EV deployment. Experts believe this strategy is suitable for India where the average travel speed is low, average distances are small and public transport is widely used. There are, however, questions about locking in investments in a few expensive electric buses when there is an enormous deficit of standard buses.

India’s opportunity is a rapidly expanding market for shared mobility—taxi aggregators. This has already started with Bengaluru-based corporate transport service start-up, Lithium Urban Technologies, the country’s first cab operator with an all-electric fleet. With a fleet of 400 vehicles having lithium batteries, the start-up offers employee transportation services in Bengaluru to firms. The company will commence operations in the National Capital Region and plans to enter Chennai and Pune.

Similarly, Uber is initiating two pilots with Mahindra in Delhi and Hyderabad, and Ola has taken a fleet of 200 EV cars from Mahindra on lease to operate in Nagpur. The Ola app sports a special icon to promote the service. EV taxis have good brand image. Need affordable strategies for battery management and charging: India needs more affordable strategies for charging and battery management. The cost of batteries dominates the total cost of EVs. India stands to gain from plummeting battery costs that has already dropped by 40 per cent since 2010, but the costs are still high. There is, therefore, growing interest in battery swapping that delinks battery ownership from vehicle ownership and reduces the ownership cost of vehicles. This reduces the high initial capital cost and the recurring cost of battery replacement.

Chetan Maini, vice chairman of Sun Mobility, a renewable energy start-up, explains, “If you separate the battery from the electric vehicle, the price of the vehicle comes down significantly, and the range is not a challenge anymore.” Swappable battery technology allows for batteries to be smaller, lighter and more efficient; thereby making the overall cost of vehicles affordable, adds Maini.

Many agree that swapping may work in buses, and in two- and three-wheeler segments, but industry experts feel this may not work in cars. The car industry fears that this can stymie innovation in integrated development of battery and EVs. Experts also believe that there can be a mismatch between the scale of investments in battery swapping and the demand for battery.

There is a limited global experience in battery swapping in China, Russia and Israel. Information available for automated battery swapping stations, called Better Place, in Israel show that capital requirements are very large and swapping requires standardisation of battery size, capacity, placement and a high level of safety.

Naveen Munjal of Hero Electric is enthusiastic about battery swapping in two-wheelers. Anup Bandivadekar says, “Swapping for buses makes sense if one can get the battery owner to assume the risk rather than the bus operator. Battery swapping does not appear to be a basket where we should put all our eggs, but there is no reason to not to explore that pathway either.”

However, India will have to plan charging network efficiently. Official policies are likely to prioritise private sector investment in charging infrastructure. This will require reforms because resale of electricity is not allowed in India. Under The Electricity Act, 2003, a distribution licence is required to distribute power from the respective state electricity regulatory commissions. Private players therefore need to work with discoms to set up charging stations. Power companies are showing strong interest in EV market. NTPC Ltd is securing a national licence to set up charging stations for EVs across states. Tata Power is also looking at the charging infrastructure. Enabling home charging will enable electrification of personal vehicles.

Need raw material access: Yet another challenge in India is the growing dependence on raw material for battery production to meet the growing demand for battery storage. This is likely to push India to another import spiral. Experts point out that metals, including lithium, manganese, cobalt, nickel and graphite, form 40 per cent of the value of batteries and are not locally available. These are largely available in China, Latin America and Africa and might require access to new mines and new trade agreements.

According to Aseem Goyal of Panasonic Pvt Ltd, that produces batteries, lithium is a small part of the value of the battery, but other metals, like cobalt, nickel and magnesium, are more expensive and might pose concerns if their supply is not ramped up. Jhunjhunwala adds that urban mining of these materials from battery recycling system will become important. Indian companies have shown that 95 per cent of these metals are recoverable from used batteries.

Need state-level action: Transformation is possible if state governments get involved. Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telengana, Delhi and West Bengal are among the leading states framing EV policies. Telengana, for instance, is framing EV procurement and tendering policy, start-up programmes and other support systems to attract investments in EVs. Delhi has dedicated funds to provide subsidy for EV purchase but its utilisation is poor. Karnataka, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Chhattisgarh have exempted EVs from the state motor vehicle taxes. But more robust local level policies are needed to scale up the EV strategy. Cities piloting EV bus programme are developing protocol for the roll out.

Win consumer confidence: Scale is possible if the customer base can be expanded. India requires massive outreach to win clientele for the EV ecosystem. They are rightly concerned about range, lack of charging facilities, battery replacement costs, limited range of products in the market and high capital costs (see ‘What customers and dealers think’,). Also financing of EVs is a barrier. Banks do not finance electric two-wheelers because these low-powered vehicles are not usually registered. Even electric car finance is tardy.

Clearly, we need to put together many pieces of the jigsaw to reach to zero emissions, which is a grand promise in India. For the first time in automotive history, India can lead a business while curbing pollution and mitigating climate impacts, and not continue to lag behind the advanced markets that have had a head start in IC engines. But India will have to be inventive to make EVs affordable and to make them work for shared and mass mobility for a final win-win and clean future.

With inputs from Polash Mukerjee, Usman Nasim, Shambhavi Shukla, Vivek Chattopadhyay, Avikal Somvanshi and Akshit Sangomla in Delhi and Chetana Borkar in Nagpur

Do you feel, like me, that an “Ah Hah” moment is just there, but we keep missing it? Just consider how

e-vehicles are now the talk of the town; how industry has technology to make fuel out of solid waste or even second-generation ethanol from bamboo and rice straw-run vehicles without pollution and change the way we do business with pollution. The technology in reach now promises to convert municipal waste and sewage into fuel. In one stroke, we de-carbonise vehicles, deal with garbage and achieve the best emission standards—better than the BS VI emission standards. The opportunity of these technologies looks immense. Exciting.

But the change on ground is so miniscule that the reality of dirty energy and dirty vehicles swamps the little benefits. Why are we not able to see the transition at the scale and pace needed? Why are we not profiting from the opportunity of a re-invented future? This is when the politician-policy narrative has dramatically changed and there is optimism and drive to push new generation technologies. No longer is the issue of air pollution, for instance, out of the table. But still. No disruption. Not yet.

Take e-vehicles. So much buzz, but in reality, we do not even have a clear policy for what we will promote and how. The Union Cabinet has recently cleared the National Mission on e-vehicles, but as yet there is huge confusion about the direction of the technology roadmap—e-vehicles or hybrid or both. Battery operated electric vehicles run entirely on electricity, while hybrid vehicles (mild, full or plug-in) combine the use of the internal combustion engine with battery. The NITI Aayog has been tasked to come up with this policy.

But the most important question is how will the transition be supported? The only supportive programme is the government’s Scheme for Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid &) Electric Vehicles (fame), with an outlay of Rs.795 crore, of which as of December 2017 someRs. 400 crore was available. The scheme has now, rightly, prioritised funding of public transport buses in cities with a high air pollution load.

Under fame, initially, there was a discussion to give some 100 buses each to five high impact cities. But now, it is down to 40 buses for nine cities and Jammu and Guwahati will get 15 buses as they are in the special category. The government subsidy is capped at Rs.85 lakh to Rs.1 crore per bus, depending on the level of localisation—15 to 35 per cent of the buses would have to be made/assembled in India. In addition, each of these 11 cities will have to spend up to Rs.5 crore for setting up the infrastructure for charging.

The other scheme for scale-up of e-vehicles is under the Energy Efficiency Services Limited (eesl), which has tendered for some 10,000 vehicles and awarded this to Tata and Mahendra Motors (70:30 ratio). It has received the first lot of 500 cars, specifically for Delhi and the National Capital Region. It is also setting up 125 charging stations in government offices, where these vehicles will be parked.

The question is what is all this adding up to? India registers over 17 million two-wheelers and over 2.5 million cars each year. The 100 e-buses will get totally lost in the over-crowded, already congested and polluted cities. This strategy of incremental change is not the way to make a transition work.

Let’s then look at what has worked. Countries that have pushed this disruptive technology have set clear and enforceable targets. China zero emission vehicle mandate requires every vehicle manufacturer and importer to ensure that 10-12 per cent sales are e-vehicles by 2019-20. This should not surprise us. The fact is that when Delhi went through its own gas transition, it was done under a specific mandate. The Supreme Court laid down that all buses and three-wheelers would be run on cng and that diesel buses would be penalised for each operational day. In just two years, the city brought in 100,000 vehicles. But today, we don’t want to discuss any tough mandate as it steps on too many toes.

Then there is the tricky issue of spending lots of money, which makes scaling up possible. There is no doubt that the Government of India should not subsidise private vehicles. Instead, here the approach should be to work with the fiscal structures to incentivise cleaner vehicles. The approach also should be to do what eesl is doing—bulk contracts to drive down price and make vehicles available to select target groups.

But none of this will work for public transport. Here government has to put money down—and much more than what is it thinking of today. The fact is that bus operations in our cities are in the red today. This is even when the bus cost has been fully depreciated. Even if the private sector is allowed to bring these buses, they will need the costs to be recovered from operations. The current bus ticket rates—the bus competes with the two-wheeler cost and even less—will not allow for profitable operations. Therefore, public money is needed to bring in good technology. No half measures will work here. Otherwise, we will have vision (lots of it) and no change.

(This is an editorial by Sunita Narain published in the 16-28th issue of Down To Earth).