When the rains began in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) on the morning of September 3, it was just another day for Vijay Gadhia. The 50-year-old employee of Jammu’s Power Development Department had gone to Srinagar with his colleagues for official work. He expected the next day to be bright and sunny. A day of rain in the region is usually followed by a day of sunshine. But the rain did not stop. Instead, he heard the news that a bus carrying 70 members of a wedding party was washed away by flash floods in Rajouri, of which 50 could not be traced.

On the night of September 4, the Doodh Ganga, a tributary of the Jhelum flowing through Srinagar, breached its embankment following a cloudburst in its catchment area. On September 5, the water level in the Tawi and Chenab rivers in Jammu rose dramatically. Flood control bunds were washed away, bridges collapsed and agricultural land got submerged. Rains continued to lash the region in the next few days triggering landslides that disrupted highways and snapped power lines. Till the afternoon of September 5, Srinagar residents were clicking photographs of the gradually swelling Jhelum to post on social media.

| CHRONOLOGY OF A DISASTER

A cyclonic circulation coupled with a fresh Western disturbance moves towards J&K September 1-2 Rainfall starts in J&K September 3 Landslides claim 10 lives across the state. The Jhelum flows a metre above the danger mark September 4 The Jhelum rises to 5.43 metre above the danger level. Flash floods in Rajouri claim 50 lives September 5 Cloudburst in the catchment area of Doodh Ganga. Jhelum breaches embankment September 6 Water level reaches 7-8 metres in parts of Srinagar. Rescue operations start September 7 Prime Minister NarendraModi calls the flood a `national calamity' September 9 Death toll stands at 215 September 11 Floodwater starts receding |

On the night of September 5, the Jhelum too breached its embankment at Padshahi Bagh, following which there was a half-hearted attempt by the state administration to warn the people. Announcements were made from several mosques in the city at 10 pm. Residents were asked to move to the first floor of their houses. But the announcements came late. Most people had gone to bed. Many of those who were awake ignored the words. According to Gadhia, it hardly sounded like a warning. Those who did not have a multi-storey building had no choice. By the time the announcements started, some parts of Srinagar were already submerged in waist-deep water.

Gadhia and his colleagues sensed trouble and fled Srinagar, spent four days in the wilderness without food and water before reaching the Shankaracharya hill on September 12. “After that we reached the Governor House from where we were airlifted to Jammu,” Gadhia told Down To Earth.

A city under water

In September, rainfall in Srinagar crossed its 10-year-high mark—151.9 mm of rainfall in September 1992—within 24 hours. This year, the city received 156.7 mm of rainfall on September 5 alone. The average monthly rainfall for Srinagar is 56.4 mm. The India Meteorological Department recorded more than 500 mm of rainfall in the first week of September. The floodwater started receding from September 11, but till September 13 more than 70 per cent of Srinagar was still submerged, with tens of thousands of people stranded.

The two distinct water channels flowing through the city—the Jhelum and the flood channel, an artificial outlet created in 1904 to drain out excess water from the Jhelum in case of flood—had merged into a big, brown lake. Some of the worst-affected areas include Allochi Bagh, Tulsi Bagh, Wazir Bagh, Rajbagh, Zero Bridge and areas along the right bank of the Jhelum. Maisuma, Natipora, Lal Chowk and several localities in Civil Lines remained submerged under two metres of water.

Murtaza Khan, a former legislator, spent three days on the roof of the MLA hostel building on M A Road. “The pace and level of rescue operation was only five per cent of the required scale. The Army or the National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) hardly knew about Srinagar. They had no idea which area was densely populated with kuccha houses and which had high-rises, nor did they know where the water currents were maximum and why,” he says.

Gadhia and Khan were lucky to have been saved, unlike the 215 people who lost their lives in the deluge. The toll is likely to rise as the water recedes. Hectares of ripe crop and orchards have been lost, and the infrastructural damage is likely to cross Rs 6,000 crore.

Kashmiris have complained about the lack of coordination among the Army, NDRF and the local administration in rescuing people. Chief Minister Omar Abdullah pleaded helplessness. “I had no government for the first 36 hours as the seat of establishment was wiped out. My own residence has no power supply, and my cellphones had no connectivity. My capital city [Srinagar] was taken out. I resumed administrative operations with six officers in a makeshift mini secretariat,” he told journalists at a press meet on September 9. According to news reports, the six-storey secretariat was submerged up to the second floor.

Abdullah added that his officers could not be located for at least three days after the floods began. “People’s anger is justified, but we were caught off guard.” His minister for irrigation and flood control, Shyam Lal Sharma, told Down To Earth that his department had given a warning which was not taken seriously. “We issued a warning on September 5. People were alerted in various parts of the state,” Sharma said.

Floods not unprecedented

Jammu and Kashmir has a long history of floods. From 1905 to 1959, the state was hit by flood 14 times. The memory of the 2010 floods in Leh was still fresh when disaster struck again last month.

In 2010, the Jammu and Kashmir Flood Control Ministry had prepared a report and issued a warning that the state is likely to face a major flood catastrophe in the next five years and that the government is ill-equipped to save lives and property. The Irrigation and Flood Control Department had proposed a Rs 2,200 crore project to put the required infrastructure in place. The report was submitted to the Union Water Resources Ministry, but nothing happened.

The Jhelum is one of the most important natural drainage channels of Srinagar, which is otherwise like a bowl having no outlet for water. Silt has accumulated in all of its major tributaries and the flood channels are blocked. The wetlands of Nadru, Nambal, Narkara Nambal and Hokarsar that absorb rainwater have been replaced by residential colonies (see ‘Srinagar’s lost saviours’). Whenitrains for two to three days, the city gets flooded with water from the Jhelum. “Srinagar faces flood every 50 years. It has a cycle. But encroachment has killed its flood channels. Bemina used to be a flood basin, but many residential and commercial buildings have come up in its place in the past 10 years,” Sharma says.

Srinagar's lost saviours

|

In flood-ravaged Jammu and Kashmir, the streets of the state’s summer capital, Srinagar, resemble surging streams. The drainage channels of the city have been blocked. The links connecting the lakes have been cut off due to unplanned urbanisation and encroachment. As a result, the lakes have lost their capacity to absorb water the way they used to a century ago, scientists say.

Wetlands and lakes act as sponges during floods. Kashmir Valley is dotted with wetlands. Apart from natural ponds and lakes, the valley has other types of wetlands, such as rivers, streams, riverine wetlands, human-made ponds and tanks. According to a report by the Department of Environment and Remote Sensing, there are 1,230 lakes and water bodies in the state—150 in Jammu, 415 in Kashmir and 665 in Ladakh. Dal Lake, Anchar Lake, Manasbal Lake and Wular Lake are some of the larger wetlands in the region which are today threatened by urbanisation. Dal Lake in Srinagar, one of the world’s largest natural lakes, covered an area of 75 square kilometre in 1,200 AD, says Nadeem Qadri, executive director of the non-profit, Centre for Environment and Law. The lake area almost reduced to one-third in the 1980s and has further reduced to one-sixth of its original size in the recent past. It has lost almost 12 metres of depth. Srinagar’s natural drainage system has collapsed making it prone to urban floods.

Half of water bodies lost

Last month, continuous rain for two to three days flooded Srinagar with water from the Jhelum. This would not have happened a few decades ago, say Humayun Rashid and Gowhar Naseem of the Directorate of Ecology, Environment and Remote Sensing, who have studied the loss of lakes and wetlands in Srinagar and its effect on the city.

They explain that deforestation in the Jhelum basin has led to excessive siltation in most of the lakes and water bodies of Srinagar. They compare two maps of the city—one of 1911 and another of 2004 (see ‘Srinagar’s lost saviours’). Their analysis shows that wetlands like Batamaloo Nambal, Rekh-i-Gandakshah, Rakh-i-Arat and Rakh-i-Khan and the streams of the Doodh Ganga and Mar Nalla have been completely lost to urbanisation, while other lakes and wetlands have experienced considerable shrinkage in the past century.

The study involved mapping of nearly 69,677 hectares (ha) in and around Srinagar. The analysis of the changes that have taken place in the spatial extent of lakes and wetlands from 1911-2004 reveals that the city has lost more than 50 per cent of its water bodies.

What went wrong

When some low-lying areas in Srinagar go under water during heavy rains, people blame the drainage system. What they don’t realise is that they have constructed their houses in those low-lying areas that were previously used as drainage basins for the disposal of storm water, says Mehrajudin Bhat, executive engineer of the J&K Urban Environment Engineering Department. “People in the city have connected their sewage lines directly to drains that are meant for the disposal of storm water. This leads to choking of drains,” he explains.

In 1971, Srinagar’s municipal limits covered only 83 square kilometres (sq km). In 1981, the area went up to 103.3 sq km. At present, urban agglomeration of Srinagar covers more than 230 sq km. This has resulted in the encroachment of wetlands and natural drainage channels, Bhat says.

Just like Srinagar, many urban centres of India have failed to manage their drainage channels and storm water drains. Mumbai learnt its lesson in July 2005. The six basins of streams that criss-crossed the city, meant to carry its monsoon runoff, had been converted into roads, buildings and slums, just like Srinagar. Kolkata, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Chennai and several other cities have been falling prey to frequent urban floods due to the degradation of their drainage network.

Legal safeguards

A few cities like Guwahati and Kolkata have taken steps to preserve their water bodies. In Guwahati, the state government passed the Guwahati Water Bodies (Preservation and Conservation) Act, 2008. The aim was to preserve wetlands and to reacquire land in the periphery of the water bodies. In 2006, the East Kolkata Wetland Conservation and Management Bill was passed to protect 12,000 ha of wetland.

The Ministry of Environment and Forests issued a rule for conservation and management of wetlands in December 2010, under the provisions of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, called the Wetlands (Management and Conservation) Rules, 2010. But the law has no teeth until a wetland is notified under it, says leading environmental lawyer Sanjay Upadhyay.

He adds that the Town and Country Planning Act should take care of the wetlands, but the municipal bodies that implement this Act do not have the technical expertise to even identify a wetland. These loopholes add to the problem of floods in urban India.

Urbanisation affects disasters just as profoundly as disasters can affect urbanisation,” writes Mark Pelling, geographer and climate change expert at King’s College, London, in his book, The Vulnerability of Cities.

In recent times, urban flooding has emerged as a major concern. As the weather gets more erratic and one-time rainfall, like the one recently witnessed in Srinagar, increases, large concentrated populations in urban areas face increased risk of flood.

There are some peculiarities of flooding in urban areas. Its primary reason is surface water runoff. Surface runoff is the excess water from rain or melting snow that flows over the earth’s surface without getting absorbed. In the urban landscape, it is controlled and managed artificially through drains which flush out the runoff from the city, unlike in rural settings where the runoff is absorbed naturally by farmlands and ponds.

Urban areas are characterised by impervious surfaces like roads, pavements and buildings. High rate of development and construction in these areas has resulted in the loss of soft landscape. This decreases a city’s capacity to absorb water, making it dependent solely on the outflow of surface water runoff. Under such circumstances, even moderate rainfall can lead to flash floods in low-lying areas. Cities located along a river might face an added problem if the river flows at a higher level within its embankment. Guwahati, a low-lying city on the bank of the Brahmaputra river, faced unprecedented flooding this year.

In the past few years, flooding in Delhi due to overflow of the city’s 18 major drains has become a common phenomenon. Heavy rain in the Yamuna’s upstream increases its water level in Delhi, due to which the drains in the city experience reverse flow.

As more and more farmlands and green areas are being urbanised, the amount of surface area for water percolation is getting reduced. As a result, all the runoff flows on the land, without being absorbed. This increases the chance of floods.

Another reason for urban flooding is the lack of drainage system in an urban area. As there is little open soil to absorb water, nearly all the excess rainwater needs to be transported to the drainage system. High-intensity rainfall can cause floods when a city’s drainage network does not have the capacity to drain away excess water in adequate time.

A 2003 study by C P Konard, published in the US Geological Survey, shows that the streams in the urban areas of the US rise more quickly than those in rural areas during storms and have higher discharge. Thus, urban spaces flood more rapidly. It also shows that debris from broken bridges and other construction that the streams collect further restrict the water’s flow from the city, increasing its level and causing floods.

Urbanisation the root CAUSE

The risk of infrastructural damage increases with increasing urbanisation. A 2013 research paper by U S De, former additional director-general of meteorology (research), Pune, analysed flooding in four megacities of the country—Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata and Mumbai. The paper demonstrated how rapid and uncontrolled urbanisation is at the root of floods and flood-related damages in these cities. It noted that the mechanism for urban flooding is complex and location-specific. Hence, each city needs its own flood management practices.

Encroachment is another fallout of urbanisation. The paper mentions that the number of water bodies in Delhi has been reduced to 600 from the original 800 due to encroachment. It notes that the floodplains of the Yamuna—home to thousands of illegal colonies—are the most populated parts of Delhi. High population density demands more infrastructure, leading to environmental degradation. By 2025, the population of tropical Asia is estimated to rise to 2.4 billion. Many of the most populated cities of the world—Tokyo, Mumbai, Shanghai, Kolkata, Jakarta, Delhi, Seoul, Manila and Dhaka—are located in Asia, three of which are in India.

Kolkata has been built on wetlands. Chennai, too, has seen massive construction in recent decades, reducing soil cover and vegetation. While other cities can expand in adjoining areas, Mumbai cannot due to its long coastline. The city was built by merging seven islands and hilly areas. Nearly 60 per cent of Mumbai’s population lives in poorly built temporary settlements. Only three outfalls (discharge point of a waste stream into a body of water) to the sea have floodgates. The remaining 102 outfalls in the city open directly into the sea. During high tide, the sea water enters the drainage system through these outfalls, causing floods.

Weather: the missing LINK

The year 2005 was recorded as the hottest year of the century. Incidentally, in the same year, the worst urban flooding was reported in Mumbai on July 26-27. During those two days, the city witnessed an unprecedented 944 mm of rainfall in 24 hours. In the same year, 10 severe urban floods were reported from across the country. Three-fourths of Chennai was inundated. It affected more than 500,000 people.

An urban nightmare

|

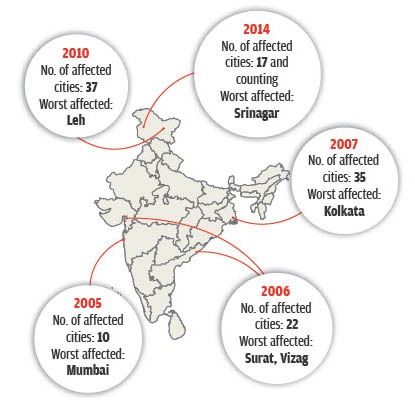

In 2006, 22 cities in India reported floods. The increasing trend of urban flooding was carried into 2007, where the number of affected cities rose to 35. Extreme weather events have increased in recent times. “Floods and droughts will become more frequent. One projection shows that the intensity and the number of tropical cyclones will increase in the next 40-100 years,” De says.

Anil K Gupta, director of the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology in Dehradun, Uttarakhand, adds that the entire Himalayan range is vulnerable because of rising temperatures. “Each and every valley—be it Kashmir, Kedarnath or Badrinath—faces the threat of increased precipitation,” he says.

According to the Jammu and Kashmir State Action Plan on Climate Change, 2013, minimum temperatures in the Himalayan region are projected to rise by 1°C-4.5°C.

The report also says that the number of rainy days in the region in 2030s may increase by five or 10. The intensity of rainfall is likely to increase by 1-2 mm per day. “What is increasing is sudden precipitation, which happened during the recent Kashmir floods,” Gupta says.

A report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change notes that every year there will be at least one extreme weather event in the Himalayas. “Last year, it was the Uttarakhand disaster. Before that we saw floods in Pakistan and cloudbursts in Jammu and Kashmir,” says Jatin Singh, chief executive officer of Skymet, a private weather forecast company. In the course of such events, many urban areas are likely to be affected, the way Srinagar was caught unawares. The India Meteorological Department (IMD) is yet to recognise that extreme weather events are a result of climate change. For the last four major natural disasters in India—Mumbai floods of 2005, Leh cloudburst of 2010, Uttarakhand disaster of 2013 and J&K floods of 2014—IMD has cited disturbances in the wind current and monsoon as reasons. It used words like “unprecedented”, “unusual” and “unique”, but offered no explanation for why these events are happening at such high frequency. In light of the complexity of urban floods, we need a comprehensive plan of action to reduce the damage thus caused.

Despite warnings from the Indian Meteorological Department and the state Irrigation and Flood Control Department, Jammu and Kashmir went under water because it did not have a contingency plan, nor did it have a well-equipped state emergency operation centre (SEOC).

One might argue that when Mumbai was hit by flood in 2005, Surat in 2006 and Kolkata in 2007, each city had functional SEOCs, yet they failed to prevent the disaster. This is because the floods they faced in those particular years were quite different from the floods they had faced earlier.

Urban floods are a new challenge. Census 2011 showed that for the first time since 1921, the urban population in India was much more than the rural population. A 2008 study by the National Institute of Disaster Management showed that the annual economic losses from urban flooding are much higher than those incurred from other disasters.

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) decided to deal with urban flooding separately. In 2008, it formed a committee on urban floods which formulated the National Guidelines for Management of Urban Flooding. The guidelines were released in 2010.

What the guidelines Say

NDMA acknowledges the increasing frequency of urban flooding. It says that the causes of urban flooding are different for each city, which is why flood management strategies need to be customised. Policies for a coastal city, for example, would have to be different from a city located on the hills.

|

NDMA proposed an Urban Flooding Cell with a technical umbrella for forecasting and warning at the state level. It mooted a local network of automatic rainfall gauges for real-time monitoring. Local authorities were asked to go in for contour mapping, put the existing storm water drainage network on geographic information system (GIS) and desilt all drains by March end every year. It also suggested that lakes should be freed from encroachment so that the natural drainage system of a city could be maintained.

Guidelines not binding

Most of the state governments have not been sincere in implementing NDMA’s guidelines. “But are the guidelines binding?” asks A K Sarma of the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Guwahati, who was a member of the committee formed by NDMA. It is up to the states to implement the rules. The state governments are not “compelled” to follow the guidelines, so nothing ever happens, Sarma adds. He says there needs to be a holistic approach to address urban floods. “While preparing the guidelines, we had the diversity of India in mind and knew that the rainfall that Jaipur receives is not the same as what Shillong receives. So we tried to cater to all types of cities,” he explains.

He adds that for proper implementation of the guidelines, various departments have to come together. For example, the problem of urbanisation is not only wrong town planning but also encroachment of wetlands and water channels, which reduces a city’s natural capacity to handle floods. To correct this, municipal corporations have to work closely with the Irrigation and Flood Control Departments. But administrative differences make it difficult to handle a disaster like urban flood.

This is evident from what happened in Srinagar. Despite repeated warnings by the Irrigation and Flood Control Department about the encroachment of the drainage channels in the city, the Srinagar Municipal Corporation failed to clear these channels.

NDMA guidelines also stress on the need to make the planning process participatory. Following the hierarchical structure of administrative systems, flood control measures are planned without the participation of the affected communities. “In many cases, this results in unsustainable measures which don’t meet the needs of relevant stakeholders,” state the guidelines.

Lessons learnt

While most cities in India are yet to wake up to the problem of urban flooding, Guwahati, which faces floods almost every year, is getting ready with an action plan. The Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA) has taken up a project in the city’s Garbhanga hill for scientific management of rainwater that flows down the hill during monsoon, triggering landslides and choking drains with silt. Siltation in the drains by sediments carried by rainwater has been identified as one of the major causes of waterlogging in the city. GMDA also plans to clear encroachments along the drainage channels of Guwahati.

GMDA is being given technical support by IIT-Guwahati, and Shristie, a city-based civil engineering firm, which focuses on plantation in the hills, development of an efficient drainage system, putting up structures on the hill to check the speed of water and rainwater harvesting. The project is touted to be the first of its kind in India.

While some states have accepted that urban floods are becoming frequent, as are extreme weather events, and are taking steps to revive their natural drainage systems, others continue to be in denial. It is time the governments woke up to the crisis of urban floods and took adequate measures to preserve the ecological balance, while keeping contingency plans ready to deal with any unforeseen disaster.

| Models of flood management

The three departments also identify flood-prone areas and undertake mitigation measures to reduce risk. In terms of infrastructure, the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority is mandated to operate and maintain flood control infrastructure across all regions of Toronto, including large dams, channels, flood walls and dykes. Arizona, a south-western state of the United States, has gone a step ahead to retain the water quality after floods. The Flood Control District is a plan to control flooding in Maricopa County, the worst-affected region of Arizona. The plan is being carried out as per the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Stormwater Programme as part of the Clean Water Act. A guide and awareness manual has been circulated among the public and local authorities on ways to prevent floodwater from entering into the water channels of the area. |