Tears well up in Naseem Haider’s eyes as he watches his 25-day-old son twitch inside the incubator. Born premature after 29 weeks, this palm-sized infant, weighing no more than a kilogram has a feeding tube piercing through one nostril and an oxygen tube through the other. His vital organs are constantly monitored via wires attached to his body.

Born in a private hospital in Uttar Pradesh’s Bijnor district, the baby was given ampicillin, the first antibiotic administered to any premature child for preventing infection. With a heart beat racing from the normal 140 per minute to 170 per minute, he was shifted to the bigger and specialised Mangla Hospital. Here, he was put on a ventilator that pumped oxygen into his underdeveloped lungs.

Three days later, he developed hyaline membrane disease, which made breathing difficult for him. He was prescribed cefotaxime, an antibiotic that costs Rs 30 per 250 milligram. The infant showed no improvement. Instead, he developed low blood pressure. Investigations showed he had acquired sepsis, a bacterial infection of blood. Doctors again changed the antibiotic—this time, to meropenem that costs Rs 300 per dose.

The baby had also contracted pneumonia caused by Klebsiella bacteria, which is resistant to all antibiotics except two. “We included polymyxin B and colistin in the infant’s regime even though their adverse effects are massive,” says his doctor Vipin Vashishtha, who runs the hospital. One dose of polymyxin B costs Rs 1,400. The infant was given one dose every day.

Haider, a taxi driver, cannot understand why the costly drugs cannot cure his son. Hospital expenses alone are between Rs 3,000 and Rs 10,000 per day. Medicines cost Rs 2,000 per day. By now, he has spent over Rs 1.5 lakh on his son’s hospital stay, investigations and medicines. With a monthly income of Rs 5,000, he already has difficulty feeding his family of six. “I have not paid the hospital bill for six days. I borrowed money from relatives and neighbours. I cannot ask for more money. I will have to take my son home,” he says.

“The infant has a slim chance of survival,” says Vashishtha, who rues that all the infections were acquired in hospital itself. “Howsoever well the equipment are sterilised, chances of infection are high in critical cases,” he says. The risk is higher for premature babies because of their weak immune system.

Vashishtha has reported 14 similar cases of antibiotic resistance in his hospital between April 2009 and February 2011.

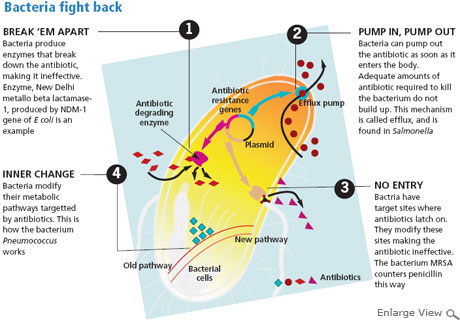

In all these cases, the antibiotics given were ineffective on bacteria (see ‘Constant one-upmanship’).

In his study, published in Indian Pediatrics in February 2011, Vashishtha writes that organisms found in the 14 infants were resistant to all classes of antibiotics—cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, monobactams, quinolones, piperacillin-tazobactam combination and carbapenems. All were administered polymyxin B and colistin, but only eight survived. Four of these eight developed complications like meningitis and arthritis.

“Doctors had stopped administering polymyxin B and colistin to patients as their use can lead to low blood count, renal problems and even seizure. But there is no antibiotic left to treat multi-drug resistant bacteria,” says a worried Vashishtha. The microbes have not yet become resistant to these two antibiotics as they have not been widely used because of their side effects and high cost.

“Doctors had stopped administering polymyxin B and colistin to patients as their use can lead to low blood count, renal problems and even seizure. But there is no antibiotic left to treat multi-drug resistant bacteria,” says a worried Vashishtha. The microbes have not yet become resistant to these two antibiotics as they have not been widely used because of their side effects and high cost.

Antibiotics become ineffective because of excessive and irrational use. “They are prescribed even for viral infections like common cold and sore throat,” says Randeep Guleria, professor of medicine at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi. This helps bacteria constantly evolve strategies to outwit the drugs. “At times, patients do not complete the course of the antibiotic so the bacteria do not get completely eliminated,” he says. World over, doctors are finding ways to slow down the process of antibiotic resistance.

Global debate

Between October 3 and 5, researchers and policy makers from 40 countries met in New Delhi as part of the first global forum on bacterial infections. Worried about the high mortality rate due to antibiotic resistance, they looked into ways to delay resistance to the remaining few antibiotics.

‘Use less antibiotics’

.jpg)

What are the options available to reduce use of antibiotics?

We have vaccines, diagnostics and antibiotic stewardship.

To what extent can these help reduce antibiotic resistance?

If effective vaccines are developed against even 10 bacterial diseases, there can be 99 per cent reduction in use of antibiotics. Vaccines are not available at present. So, vaccination cannot be the only strategy. Better diagnostics can reduce use of antibiotics, but it is expensive. As of now, stewardship is the most important option. Programmes held in hospitals and private clinics to ensure correct use of antibiotics will help. Eighty per cent of our efforts should be in this.

What does the future hold?

Industry is developing a vaccine to prevent hospital infections. Diagnostics using microbial DNA and human antibodies will help reduce antibiotic use. Gene Expert, a diagnostic kit for multi-drug resistant TB, has shown this. |

|

|

The meeting was organised by Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership (GARP), launched three years ago. It is a project of the Washington-based non-profit Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy. The partnership is mandated to develop policies on antibiotic resistance for four low- and middle-income countries—India, Kenya, South Africa and Vietnam.

Participants pressed for striking a balance between access and irrational use of antibiotics. This, said experts, should be through restricting availability of new antibiotics in the community. There should be higher reliance on vaccines to reduce the disease burden. Hospitals can formulate their own infection control policy. They also proposed a ban on sub-therapeutic use of antibiotics in animals. They sought the support of governments, researchers, industry and consumers for the purpose.

Experts at the GARP meet said studies show a steady growth in use of antibiotics in India (see ‘Sales grow’). Of all the antibiotics, the beta-lactams, like penicillin, were sold the most followed by quinolone antibacterials, like ciprofloxacin. Penicillin is used to treat, among others, wound infections. Ciprofloxacin is given to patients with urinary tract infections.

In line of bacterial fire

Independent studies demonstrate the immensity of the problem in India, be it due to infection acquired in hospitals or in the community.

Doctors classify infections developed 48 hours after reaching the hospital as hospital acquired infections (HAI). Those acquired before 48 hours are community-acquired. “Of all the bacterial infections 80 per cent are community-acquired,” says Anita Kotwani, associate professor at Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute in Delhi.

‘It is an urban problem’

.jpg)

How will you balance access and antibiotic resistance?

Access to effective medicine and drug resistance is not necessarily a dichotomy. Drug resistance is highly variable. It is not yet a problem in rural areas. But city hospitals use antibiotics more than they need.

Will the Indian policy on antimicrobial resistance be able to check over-the-counter sale of antibiotics?

India will never be able to ban over-the-counter sale of antibiotics. You cannot stop people from going to drug stores to buy medicines. No one can keep a check on that.

What is the solution to the problem?

Basic drugs should be made available to people. Protocols to diagnose common diseases can be set. Medicines can be given to auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), trained specifically for the purpose, so that they can treat patients. If the symptoms do not fall under the protocol, the patient can be referred to a doctor without being given the medicine. ANMs are very capable of doing this. Penicillin, for some reason, works in India. This can be administered by ANMs. It can cure diseases like pneumonia, which kills many children. The more effective medicines can be kept in hospitals.

|

|

|

A study released by GARP in March this year shows that chances of contracting vancomycin-resistant enterococcus, which cause a dangerous skin infection, are five times higher in Indian ICUs than in the rest of the world.

A study conducted in a tertiary hospital in Bengaluru in 2007 found that 36 per cent of Acinetobacter, which causes HAI, had become resistant to ciprofloxacin. Another study in 2008 conducted in Benaras Hindu University showed more than 80 per cent of the isolates of Acinetobacter in hospitals were resistant to second and third generation cephalosporins, aminoglycosides and quinolones.

Researchers at AIIMS found that in the recent years Salmonella, that causes typhoid, has become resistant to ciprofloxacin. This antibiotic had replaced ampicillin and chloramphenicol.

Researchers at the Indian Council of Medical Research found Shigella, a diarrhoea-causing bacterium, resistant to cephalosporins in Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The antibiotic was adopted to counter the bacterium after it became resistant to quinolones. Up to 14 per cent of the stool samples with Shigella showed resistance to three third-generation drugs, indicating grave danger to public health.

The situation is grim in urban slums as well. In a study conducted on people of Kolkata’s slums between 2004 and 2009, a team of National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases found highly resistant Vibrio cholerae strains. These were resistant to tetraglycine, the drug of choice for cholera. In May 2011, a team of scientists found highly resistant varieties of E coli and Klebsiella in the gut of patients.

All around us

Antibiotics have made their way to the environment as well. Cattle, for instance, harbour resistant bacteria that could pose a problem to humans who come in contact with them.

‘Innovation-deficient industry’

.jpg)

Why are most drug companies walking out of antibiotic development?

A drug takes about 10 years to enter the market after being discovered. Its patent life is 20 years, after which it becomes generic. By this time the antibiotic becomes resistant. Pharmaceutical companies do not see attractive incentives in this business. There is deficiency of innovation in the industry.

So what is the way out?

Companies and research institutions should collaborate on a risk-reward-resource sharing basis to discover novel drugs and vaccines. Chances of developing resistance are least in vaccines. Except in acute cases, it is best to strengthen man’s immunity than use antibiotics. This is what bacteria do. They become resistant before being attacked. We have to strengthen our collective immunity. Bacteria have been around for several billions years before man and know how to survive.

What is the status of vaccine research?

Despite the potential of this tool, we are yet to find the right way to use it.

What is your organisation working on?

As a drug discovery innovation subsidiary we are developing new molecules to fight resistance either by directly hitting the bacteria or their defence mechanism. We are focusing on developing stronger beta-lactamase inhibitors since these molecules will restore the activity of earlier antibiotics by simply inhibiting the enzymes that destroy them. |

|

|

In 2006, researchers at the department of veterinary microbiology in West Bengal University of Animal and Fishery Sciences isolated 14 strains of E coli from the faecal samples of two cows and six diarrhoeic calves. Ten strains were resistant to at least one of the antimicrobial agents tested. Multiple antibiotic resistance was frequent. In 2008, multiple drug-resistant strains of E coli were found in calves in Gujarat.

Resistant bacteria are also lurking in rivers and sewage, risking lives of those living in the vicinity. In 2009, scientists at the Indian Institute of Toxicology Research (IITR) studied several locations along the banks of the Ganga at Kanpur. They found four species of the genus Enterococcus resistant to many antibiotics, including that which treats tuberculosis. The authors contended that enterococci makes its way to the river through sewage from hospitals, industries and households. “The Ganga is a source of drinking water,” says Rishi Shanker, senior scientist at IITR. “People depend on it for bathing and washing. Pilgrims bathe in it. Travel and tourism leads to spread of resistant bacteria,” he says.

A similar study conducted by a Swedish team of scientists, published in February this year found high levels of resistant genes in bacteria in a river in Patancheru near Hyderabad that receives waste from pharmaceutical firms. In 2009, another study had documented high levels of antibiotics like ciprofloxacin at the site. Researchers noted that the bacteria found in the river, even if not harmful, could easily transfer the resistant genes to other life-threatening bacteria, creating a worldwide problem.

A strong selection pressure by antibiotics in the environment could contribute to resistance. It is difficut to assess at what pace bacterial infections become untreatable, says Joakim Larsson, professor at the University of Gothenburg, who was a part of the team that conducted the study in Hyderabad.

The price we might pay for living with the risk could turn out to be very high, he adds.

“Doctors had stopped administering polymyxin B and colistin to patients as their use can lead to low blood count, renal problems and even seizure. But there is no antibiotic left to treat multi-drug resistant bacteria,” says a worried Vashishtha. The microbes have not yet become resistant to these two antibiotics as they have not been widely used because of their side effects and high cost.

“Doctors had stopped administering polymyxin B and colistin to patients as their use can lead to low blood count, renal problems and even seizure. But there is no antibiotic left to treat multi-drug resistant bacteria,” says a worried Vashishtha. The microbes have not yet become resistant to these two antibiotics as they have not been widely used because of their side effects and high cost.

In March 2011, the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare formulated the National Policy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance. It woke up to the threat of antibiotic resistance after a study, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in September 2010, showed that patients in Tamil Nadu and Haryana had bacteria with the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) gene. This makes bacteria resistant to many antibiotics. Spread across Pakistan and Bangladesh, the gene is common in the subcontinent.

In March 2011, the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare formulated the National Policy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance. It woke up to the threat of antibiotic resistance after a study, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in September 2010, showed that patients in Tamil Nadu and Haryana had bacteria with the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) gene. This makes bacteria resistant to many antibiotics. Spread across Pakistan and Bangladesh, the gene is common in the subcontinent. But some doctors and public health experts have criticised the new policy. “This is discrimination,” says Abhay Bang of Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health, a non-profit based in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra. “If the policy is implemented, people in rural areas will have to travel long distances to cities for a third-generation antibiotic. This is not equity.”

But some doctors and public health experts have criticised the new policy. “This is discrimination,” says Abhay Bang of Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health, a non-profit based in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra. “If the policy is implemented, people in rural areas will have to travel long distances to cities for a third-generation antibiotic. This is not equity.”