The state's industrialisation drive has been detrimental for agricultural growth on the whole. But it has not always harmed farmers. In some cases, land has been acquired below the market price, in others, market-driven transactions have been embraced by farmers, presumably because they have benefited, if only in the short term.

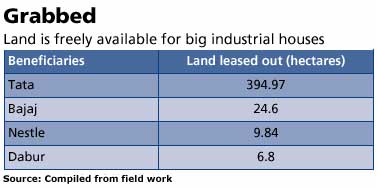

The state's industrialisation drive has been detrimental for agricultural growth on the whole. But it has not always harmed farmers. In some cases, land has been acquired below the market price, in others, market-driven transactions have been embraced by farmers, presumably because they have benefited, if only in the short term. "Terai lands are some of the most fertile not only in the state but in the country. And in less than three years, nearly 2,225 ha of land have been occupied in the terai by industrial giants," says Rajiv Lochan Shah, a social activist based in Uttaranchal. About 1,350 ha of productive farm land in Pant Nagar, 475 ha in Sitarganj and 345 ha in Kashipur have been acquired in this way," says Rupesh Kumar Singh of The Sunday Post, a weekly published from Haldwani. sidcul has converted a total of around 2,170 ha of productive agricultural land into industrial estates.

"Terai lands are some of the most fertile not only in the state but in the country. And in less than three years, nearly 2,225 ha of land have been occupied in the terai by industrial giants," says Rajiv Lochan Shah, a social activist based in Uttaranchal. About 1,350 ha of productive farm land in Pant Nagar, 475 ha in Sitarganj and 345 ha in Kashipur have been acquired in this way," says Rupesh Kumar Singh of The Sunday Post, a weekly published from Haldwani. sidcul has converted a total of around 2,170 ha of productive agricultural land into industrial estates.

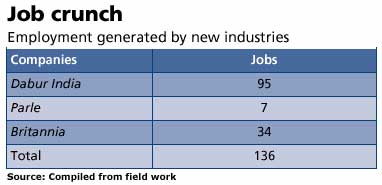

If official pronouncements are to be taken seriously, the loss of land will be compensated by the generation of employment opportunities. The state industrial policy lays a high rhetorical priority on improving standards of living and providing employment to all under a 10-year scheme. The problem is that local people are not getting jobs in the new factories. "According to an employment office at Rudrapur, in the last two years only 136 local people have been employed in the new industries (see table Job crunch)," says Rajiv Lochan Shah.

If official pronouncements are to be taken seriously, the loss of land will be compensated by the generation of employment opportunities. The state industrial policy lays a high rhetorical priority on improving standards of living and providing employment to all under a 10-year scheme. The problem is that local people are not getting jobs in the new factories. "According to an employment office at Rudrapur, in the last two years only 136 local people have been employed in the new industries (see table Job crunch)," says Rajiv Lochan Shah.

In many cases, land is obtained with false assurances of employment. Villagers of Kashipur were conned in this way when the India Glycols factory bought land from them. Today, the factory employs 579 people. Of the 244 executives and 64 trainees and apprentices none are from the area. Of the junior staff (271) only 30 per cent are local people. "Fissiparous tendencies cannot be ruled out in the near future if such a system persists," warns Rawat.

In the headlong rush towards industrialisation, environmental concerns are also being brushed under the carpet. "Nearly 24,000 trees have been felled for the extension of an industrial area to entrepreneurs in Sitarganj," says Keval Krishna Dhal, a social activist based at Sitarganj. "The forests of Barakoli range near Sitarganj and Kalapani khatta near Chorgallia in Nainital district have now been earmarked as the next target to be felled by industrial encroachers." The impact of industrial growth has clearly not been factored in. "Effect of pollution generated by these industries on environment and on the agricultural fields/crops in areas surrounding the estates has not been considered," says Rajiv Lochan Shah. "When the state government has got no control over polluting units at present, how will pollution from so many big industries be tackled?" he asks. There have been reports of several paper, sugar and distillery units polluting air, water, and land in the terai (see 'No respite', Down To Earth, November 15, 2006).

|

It's not just a question of land acquisition or deforestation. One of the fallouts of industrialisation is environmental degradation through topsoil quarrying to serve construction needs in industrial estates. There is a caveat though. Farmers are actively involved in this enterprise because they make decent money through it.

Vast tracts of fertile agricultural land in Dineshpur, Kalinagar, Transit Camp, Ramnagar, Matkota, Kichha, Gadarpur, Chakki More, and Sitarganj of Udham Singh Nagar have been transformed into soil quarries. In Sitarganj, a number of villages -- Bangaria, Sadhu Nagar, Sant Puram, Nakulia -- have become centres of quarrying. Soil is removed up to a depth of three metres, with hundreds of trucks transporting it to estates through the day and even at night.

At present, the Tharu and Buksar tribes, who have owned land here since the 13th century according to local lore, were earning as much as Rs 4 lakh for every ha/metre of land brought under mining. "I have earned Rs 8,000 for selling the topsoil from one bigha (0.25 ha) of land. This is more than what I would have earned from farming," says Govind Bisht of Nakulia village. More and more farmers are selling fertile soil. The price of soil has shot up to Rs 8-16 lakh per ha/metre and farmers are earning fortunes.

All this is in violation of the 1971 Land Act, an extension of the 1950 Uttar Pradesh zamindari abolition act, which prohibits excavation, mining or selling of farmland in the terai. But, in a way, that is a small violation. The state's land reform act of 2003 prohibits leasing or sale of farmland to private entrepreneurs from outside the state in the first place -- that's obviously not being followed.

While the short-term returns are good for the farmers, in the long run the land and its people are bound to suffer. "Only about an inch of soil is formed every 500 to 1,000 years. Any loss of good topsoil is a serious concern since the removal of topsoil reduces the fertility of the land by as much as 50 per cent," says Raghubir Chand, professor, department of geography, Kumaon University. "Additional soil for construction in industrial areas should be taken from a place where it does not damage the local ecology. Soil must come from non-agricultural and barren land. Agricultural land should not be touched."

|

| In the well-known Panchatantra story, a monkey wanting to cross the mighty Ganga befriends a crocodile. But a while into their friendship, the reptile’s intentions turn sinister he and his wife want the monkey for lunch. The simian senses this and tricks the crocodile to get to safety. The story concludes with the monkey addressing his former friend from the safety of a tree “I couldn’t have antagonised you when we were in the river. So, I had little option but to trick you when your intentions became clear.” Besides showing the monkey’s guile, the story alludes to a significant ecological fact crocodiles are top predators of river systems.

Versions of the fable are aplenty. Ancient and medieval Indian literature has references to the uneasy relations between humans and the reptile |

|

people dependent on rivers couldn’t afford to antogonise the

top predator of the water bodies. Accounts of 18th and 19th European

travellers to India also carry references to the crocodile.

people dependent on rivers couldn’t afford to antogonise the

top predator of the water bodies. Accounts of 18th and 19th European

travellers to India also carry references to the crocodile.

Gharials prefer living in deep waters of free-flowing rivers. Like tigers in the forest, gharials and other crocodilians are top predators in the aquatic system and thus are good indicators of state of an aquatic ecosystem. The reptiles feed on fish and keep all species under control, not allowing any other species, including ones that are invasive, to dominate the ecosystem. Gharials prefer living in deep waters of free-flowing rivers. Like tigers in the forest, gharials and other crocodilians are top predators in the aquatic system and thus are good indicators of state of an aquatic ecosystem. The reptiles feed on fish and keep all species under control, not allowing any other species, including ones that are invasive, to dominate the ecosystem.These reptilian predators usually feed on fish that are of no value to humans. They also feed on weak and sick fish and help control fish populations and keep river water clean and uncontaminated by their scavenging. The presence of crocodiles is an indication of a clean aquatic environment. Overfishing and pollution in rivers affect the gharial’s prey, ultimately affecting their survival. |

| Cover story special package |

|

Croc can't go on | Tears for the crocodile | Pyrrhic victory | Where to live? | Lost manhood | Where to croc? |

|

|

|

|

|

Sixteen crocodile rehabilitation centres and five crocodile sanctuaries -- National Chambal Sanctuary (ncs), Katerniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary (kws), Satkosia Gorge Wildlife Sanctuary, Son Gharial Sanctuary and Ken Gharial Sanctuary -- were established between 1975 and 1982.

Sixteen crocodile rehabilitation centres and five crocodile sanctuaries -- National Chambal Sanctuary (ncs), Katerniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary (kws), Satkosia Gorge Wildlife Sanctuary, Son Gharial Sanctuary and Ken Gharial Sanctuary -- were established between 1975 and 1982.| Cover story special package |

|

Croc can't go on | Tears for the crocodile | Pyrrhic victory | Where to live? | Lost manhood | Where to croc? |

In 1982 a report by Antoon de Vos, a wildlife biologist, for the fao/undp pronounced Project Crocodile as one of the most successful conservation projects in the world. And in 1991, the Union ministry of environment and forests felt that the project had served its purpose, and stopped funds for its captive breeding programme. Funds were also withdrawn for the egg collection programme. The thousands of crocodiles seen in various rearing stations and captive breeding centres were testimony enough for success.

In 1982 a report by Antoon de Vos, a wildlife biologist, for the fao/undp pronounced Project Crocodile as one of the most successful conservation projects in the world. And in 1991, the Union ministry of environment and forests felt that the project had served its purpose, and stopped funds for its captive breeding programme. Funds were also withdrawn for the egg collection programme. The thousands of crocodiles seen in various rearing stations and captive breeding centres were testimony enough for success.

De Vos had suggested stepping up the monitoring of released gharial to determine the continued effectiveness of Project Crocodile.In 1997-1998, monitoring exercises by the forest departments of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh located over 1,200 gharials and over 75 nests in ncs. But no survey was carried out between 1999 and 2003. And the 2003 survey showed catastophic results. Gharial numbers (including adults, subadults and juveniles) had plummetted to 514 -- a near 60 per cent decline from the status in 1998.

Experts immediately cast a doubt on the monitoring exercises. "Carrying out census surveys of endangered species like the gharial should be a routine function of wildlife departments. But scant attention is paid to species other than mammalian mega-fauna like the tiger, elephant and rhino," says Whitaker. H R Bustard, eminent reptile biologist and fao consultant to Project Crocodile, agrees. "It was lack of quantitative information on its status, and hence absence of any remedial action, that had brought the gharial to the verge of extinction in 1974," he says.

"In 2002, there were 302 adult gharials in India and Nepal. Their numbers have fallen to 145 in 2006," says Whitaker. What happened to the thousands of gharials that were bred and released in the wild? Whitaker says that conservation strategies conflicted with livelihood needs of local people. Designating large tracts of rivers as inviolate meant keeping local communities away from what used to be fishing grounds. Besides, gharial skin was an item of trade and the crocodile's eggs was food to many before wpa came into force. A lot of people felt shortcharged by the act.

"In 2002, there were 302 adult gharials in India and Nepal. Their numbers have fallen to 145 in 2006," says Whitaker. What happened to the thousands of gharials that were bred and released in the wild? Whitaker says that conservation strategies conflicted with livelihood needs of local people. Designating large tracts of rivers as inviolate meant keeping local communities away from what used to be fishing grounds. Besides, gharial skin was an item of trade and the crocodile's eggs was food to many before wpa came into force. A lot of people felt shortcharged by the act.

Bustard had anticipated such trouble. To address this problem, Project Crocodile had suggested selective culling of crocodiles that would produce substantial revenue for local people. The project actually had provisions for people's participation. It had called for protecting the immediate and long-term interests of fisherfolk who live along pas by providing them an alternative source of income. Most importantly, it mandated commercial crocodile farming, so that people could earn from conserving crocodiles and their habitats.

The 1983 notification under wpa, however, closed all doors to this approach. Since the gharial was placed under schedule 1 of the act, all trade in crocodile skin was prohibited.

In ncs, India's largest gharial protection reserve, officials are learning belatedly the pitfalls of conservation sans local participation. The sanctuary has been dogged by sand mining in recent times.

In ncs, India's largest gharial protection reserve, officials are learning belatedly the pitfalls of conservation sans local participation. The sanctuary has been dogged by sand mining in recent times.

This activity provides livelihoods to many, especially after droughts in the last four years have made agriculture unviable in the region around ncs. Sand mining has official sanction in village Piprai in Madhya Pradesh's Morena district (see box A loophole). The district administration gives contracts for sand mining amounting to around Rs 8 crore every year. But operations have spread to 50 other villages, illegally. Forest officers in Morena, say on condition of anonymity that the annual turnover from illicit sand mining is more than Rs 20 crore and involves powerful mafias.

| A loophole When the National Chambal Sanctuary was re-notified in 1983 (originally notified in 1979) to include a kilometre on either side of the river, one village, Piprai, falling in this range was left out. Divisional forest officer, Morena, M K Sharma says, “This was due to a mistake in mapping.” The revenue department of the district seized its opportunity and leased out land of about 108 hectare for sand mining. Since 2001, a case filed by Madhya Pradesh’s forest department to include Piprai village in the protected area has been pending before the Madhya Pradesh High Court’s Gwalior bench. |

Villagers operate about 500 tractors in the 50 villages that are the centre of sand mining. Those who don't have a cut in this line have their own avenues of making money. "We charge Rs 10 from each tractor that passes through our agricultural fields," says Sultan Singh, a resident of Barbasin village in Morena district. It's another matter that fields of people like him have no crops. The sandminers' tractors help them keep a pretence of ploughing and at the same time brings precious cash during times of drought.

Villagers operate about 500 tractors in the 50 villages that are the centre of sand mining. Those who don't have a cut in this line have their own avenues of making money. "We charge Rs 10 from each tractor that passes through our agricultural fields," says Sultan Singh, a resident of Barbasin village in Morena district. It's another matter that fields of people like him have no crops. The sandminers' tractors help them keep a pretence of ploughing and at the same time brings precious cash during times of drought.  Experts and even wildlife officials reason that matters could have been different had Chambal been declared a pa after giving due consideration to local people's needs. They say that the authorities could have done well to have adhered to the Guidelines for Wetland Management notified by Union government in 1992. The document offers a good roadmap for wetland conservation, with support of local people. Many also accept that given drought conditions, people have no option but to turn to sand mining.

Experts and even wildlife officials reason that matters could have been different had Chambal been declared a pa after giving due consideration to local people's needs. They say that the authorities could have done well to have adhered to the Guidelines for Wetland Management notified by Union government in 1992. The document offers a good roadmap for wetland conservation, with support of local people. Many also accept that given drought conditions, people have no option but to turn to sand mining.  The management plan aims to increase the number of gharials in the sanctuary to 1,000. There is also a proposal to relocate villagers within 1 km of the sanctuary. This has incensed villagers. Janak Singh of Khandoli village in Morena district, for example, says, "We will have to give away almost all our land if this proposal is ratified. Why should we sacrifice our land for gharials." The forest department, however, disclaims that any move to relocate people is doing the rounds.

The management plan aims to increase the number of gharials in the sanctuary to 1,000. There is also a proposal to relocate villagers within 1 km of the sanctuary. This has incensed villagers. Janak Singh of Khandoli village in Morena district, for example, says, "We will have to give away almost all our land if this proposal is ratified. Why should we sacrifice our land for gharials." The forest department, however, disclaims that any move to relocate people is doing the rounds. | Cover story special package |

|

Croc can't go on | Tears for the crocodile | Pyrrhic victory | Where to live? | Lost manhood | Where to croc? |

|

| Once released in the wild, many crocodiles are swept away by floods. Many stray into unprotected areas and get trapped in fishing nets protected area has been pending before the Madhya Pradesh High Court’s Gwalior bench. |

|

Shrinking space Katerniaghat habitat circumscribed by barrage |

|

| Cover story special package |

|

Croc can't go on | Tears for the crocodile | Pyrrhic victory | Where to live? | Lost manhood | Where to croc? |

| Bad numbers |

|

Katerniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary 58 gharials 28 adult females, 4 adult males, 8 sub-adults and 18 juveniles in 2006 |

| National Chambal Sanctuary 323 gharials 44 yearlings, 154 juveniles, 39 sub-adults, 82 adult females and 4 adult males in 2006 |

| Son Gharial Sanctuary 25 gharials in a 160-km stretch of river in the sanctuary; only two nests (meaning two females) in 30 years |

| Ken Gharial Sanctuary 10 adult gharials. No adult males observed Satkosia Gorge Wildlife Sanctuary 2 known gharials in 2006, despite about 700 being released since 1980 |

At night, the river cools slowly, so the gharials remain submerged. Sand mining and fluctuations in water-levels upset this behaviour, affecting breeding habits and, therefore, the sex ratio.

At night, the river cools slowly, so the gharials remain submerged. Sand mining and fluctuations in water-levels upset this behaviour, affecting breeding habits and, therefore, the sex ratio.| Cover story special package |

|

Croc can't go on | Tears for the crocodile | Pyrrhic victory | Where to live? | Lost manhood | Where to croc? |

WILDLIFE officials say the population of wild adult gharials is 180, which is probably an overestimate, with fewer than 20 adult males. Gharials are now 20 times more endangered than tigers, Whitaker says. When news of the drastic decline of the gharial was relayed to the Crocodile Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union some of its members reacted by starting the Gharial Multi-Task Force.

WILDLIFE officials say the population of wild adult gharials is 180, which is probably an overestimate, with fewer than 20 adult males. Gharials are now 20 times more endangered than tigers, Whitaker says. When news of the drastic decline of the gharial was relayed to the Crocodile Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union some of its members reacted by starting the Gharial Multi-Task Force. "We have bred thousand of gharials in captivity, now it's time to focus on habitat as a whole. Captive breeding and rearing was successful but it was difficult to keep the crocodiles within the confines of a pa," says Pandey. He has a point. Even when they are not swept away by the monsoon deluge, many gharials make their way outside the protected tracts of the rivers. This happens because the current practice is to release gharials in lower reaches of pas instead of releasing them near the sources, the earlier practice that gave the animals room for manouevre without straying out of their protected habitats, Basu says. Once outside, they are vulnerable to fishing nets.

"We have bred thousand of gharials in captivity, now it's time to focus on habitat as a whole. Captive breeding and rearing was successful but it was difficult to keep the crocodiles within the confines of a pa," says Pandey. He has a point. Even when they are not swept away by the monsoon deluge, many gharials make their way outside the protected tracts of the rivers. This happens because the current practice is to release gharials in lower reaches of pas instead of releasing them near the sources, the earlier practice that gave the animals room for manouevre without straying out of their protected habitats, Basu says. Once outside, they are vulnerable to fishing nets. "That is why we need an ecosystem approach to conservation. We can't just look at a single animal, species, or piece of land in isolation from all that is around it," says Choudhary. "Gharial cannot be conserved effectively within the boundaries of a pa, we are not going to restore aquatic resources with just captive breeding centres. We must look on watersheds as one ecosystem," he explains. The ecosystem approach accords significance to all biological resources within a watershed and considers the economic health of communities within that watershed.

"That is why we need an ecosystem approach to conservation. We can't just look at a single animal, species, or piece of land in isolation from all that is around it," says Choudhary. "Gharial cannot be conserved effectively within the boundaries of a pa, we are not going to restore aquatic resources with just captive breeding centres. We must look on watersheds as one ecosystem," he explains. The ecosystem approach accords significance to all biological resources within a watershed and considers the economic health of communities within that watershed.

Pacific example Swamps and wetlands cover a significant portion of the land area of Papua New Guinea. In many of these areas, crocodiles constitute a significant economic resource. They once faced extinction because of rampant hunting for the leather trade. In the early 1970s, the Papua New Guinea government banned trade in crocodile skins with more than 51 cm belly width, to protect crocodiles of breeding age. But it also started a series of small-scale schemes for rearing crocodiles in captivity, involving a hundred villages. Swamps and wetlands cover a significant portion of the land area of Papua New Guinea. In many of these areas, crocodiles constitute a significant economic resource. They once faced extinction because of rampant hunting for the leather trade. In the early 1970s, the Papua New Guinea government banned trade in crocodile skins with more than 51 cm belly width, to protect crocodiles of breeding age. But it also started a series of small-scale schemes for rearing crocodiles in captivity, involving a hundred villages.There were teething troubles, however extreme seasonal variations in water levels left the rearing pens flooded during certain parts of the year and too dry in others. The pumps required to maintain a constant water level were beyond the economic means of most villagers. All this made crocodile rearing less profitable than hunting in the wild. To circumvent this, the government started another project in collaboration with FAO/UNDP in 1977. Crocodile-rearing operations were concentrated on medium- and large-scale commercial farms. Small-scale village operations were converted into crocodile collection stations. Villagers were paid a government-set fee to collect young live crocodiles in the wild which were then transported to the rearing stations. Since the government price for the live young crocodiles was higher than that paid by traders, poaching was effectively reduced. This experiment has been emulated in Jayapura, Indonesia. Here, operations are run by a crocodile cooperative, Koperasi Yarui — the local name for the freshwater crocodile. Each village hunter gives 10 per cent of his earnings to the cooperative, which ensures fair prices for the crocodiles and supplies of needed inputs. The money generated has also permitted the building of a school, a medical post and a church. |