20 years of RTI Act: Reviving the spirit of the Act requires a multifaceted approach

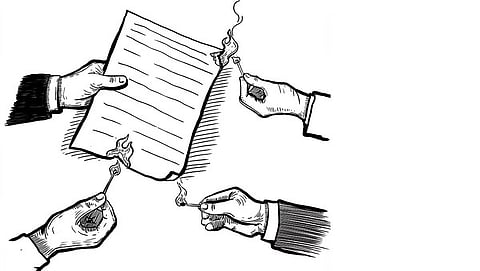

The Right to Information (RTI) Act marked a significant transformation in Indian governance by institutionalising citizens’ access to government information. Initially hailed as a revolutionary measure to ensure transparency, promote accountability, and combat corruption, the RTI system later faced challenges such as debilitating legislative amendments, systemic delays, the erosion of institutional autonomy, and threats to RTI activists.

The RTI, achieved after a long struggle for good governance and transparency, is only a small part of the RTI Act. Yet, it proved to be a miracle. It evolved along with several progressive laws during the second term of the Congress Party-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA). It can be claimed that the RTI changed the definition of constitutional good governance by giving citizens the right to obtain information from public authorities.

The three pillars of democracy are the executive, the judiciary, and the legislature. Despite its shortcomings, the media is considered the fourth pillar. The RTI led to the emergence of a new fifth pillar: civil society. Unfortunately, all four pillars have failed constitutional law. The legislature, in particular, has attempted to weaken the RTI. The Right to Education (RTE) has failed to educate the executive.

Ray of hope

The RTI, enacted in 2005, was envisioned as a foundational step towards participatory governance in India. Along with the Right to Education Act (2009) and the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (2005), the RTI represented a legislative effort to operationalise constitutional ideals. However, the RTI system in India today faces existential threats. Successive governments have weakened its institutional framework, limited its scope through amendments, and allowed systemic inefficiencies to erode public trust.

RTI empowers citizens to question government officials, investigate expenditures, and access official documents. Notable cases such as the Adarsh Housing Scam, the Commonwealth Games Scam, and the black money scandal were all made possible by RTI-based disclosures. The ability to access the money usage records of MPs and MLAs has strengthened public oversight. Furthermore, RTI has fostered investigative journalism and digital activism. For example, Afroz Alam Sahil used RTI to access health ministry data, leading to a 70 per cent reduction in the prices of over 315 essential medicines. Platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, and alternative media sources are increasingly using RTI responses to expose government failures.

Section 4 of the RTI Act mandates public authorities to proactively publish critical information. While this provision was initially enforced with some rigour, bureaucratic resistance and institutional inertia have weakened its effectiveness. However, some state-level initiatives are noteworthy, such as Maharashtra’s establishment of an online database of RTI applications and responses, making information keyword-searchable.

Similarly, Gujarat has introduced user-friendly practices. These include measures such as a free front page, photo access to files, and efficient grievance redressal. According to reports, its Information Commission resolved approximately 10,000 cases by 2018, with negligible backlog. Courts have consistently upheld the broad mandate of the RTI. For example, the Karnataka High Court ruled that the Nirmiti Kendra (a state-funded institution) fell within the scope of the RTI and penalised it for refusing to disclose information. Such judicial interventions strengthen the RTI system and reaffirm its relevance in governance.

Legislative hurdles

The 2019 amendment to the RTI Act empowered the central government to determine the tenure, salaries, and service conditions of Information Commissioners, undermining the very essence of institutional independence. Scholars and civil society activists have argued that this opens the door to executive interference and political appointments, undermining the credibility of RTI adjudication bodies. The latest attack came from the Data Act. It amended the RTI to provide a broad exemption for all personal data and removed the public interest provision. This restricts access to essential information related to the conduct, assets, and implementation of government officials, crippling mechanisms like social audits. It has virtually eliminated transparency. The removal of the public interest provision undermines the very essence of RTI, which ensures that confidentiality does not conceal public misconduct.

Institutional inertia

The next blow came from the executive, consisting of the political government and its supporting officials, who are well aware that RTI is incompatible with the ethic of accountability. They do not believe in it. This has led to widespread institutional delays in RTI implementation, such as:

More than 314,000 appeals were pending as of mid-2022 (Central Information Commission Annual Report, 2022)

Many State Information Commissions, especially those in Jharkhand, Tripura, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, are either inactive or inefficient.

Only four per cent of public information officers were punished for violations between 2015 and 2023.

Additionally, high rates of rejections on technical grounds and excessive use of Section 8 exemptions by ministries are seriously impacting the reach and effectiveness of the law.

The government is happy to withhold information, while the opposition doesn’t care. A culture of non-compliance is rampant. Only four per cent of public information officers were penalised from 2015 to 2023. In Tamil Nadu, only 21 penalties were imposed in nearly 14,000 cases in 2024. Furthermore, key ministries strategically reject applications citing Section 8 exemptions. The RTI filing process itself is fraught with bureaucratic hurdles. For example, in Delhi, 60 per cent of RTI appeals are rejected on technical grounds such as incorrect format or language. Most filed RTI applications are ultimately rejected.

The RTI Act operates as per its provisions, and the government allocates funds for it. It was hoped that RTI would be used to raise public awareness. However, awareness levels remain low, especially in rural areas. According to Lokniti-CSDS, only 12 per cent of people in rural India and about 30 per cent in urban India are aware of RTI. The infrastructure required for RTI applications is often inadequate, further exacerbating inequalities. Furthermore, misuse of the law through frivolous or malicious RTI applications is increasing, burdening the system and reducing its efficiency.

Danger to workers

You can call it whistleblowing or some other fancy name, but it is the murder of a ‘warrior’. RTI activists regularly face violent repercussions. RTI users often face physical harm, threats, and false legal cases. According to a 2023 report by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, more than 51 RTI activists have been murdered since 2005, and over 300 have been harassed or attacked. The Whistleblower Protection Act (2014) is poorly implemented, providing little practical protection.

The way forward

Most activists demanded the restoration of fixed tenures and salaries for Information Commissioners through legislation. Since the UPA enacted the law, the National Democratic Alliance would not agree to it. Many, including this author, believed this would help protect commissions from executive interference and ensure impartial oversight. This would require either repealing the 2019 amendment or passing a new law ensuring fixed tenures and service conditions for Information Commissioners, and establishing a transparent, bipartisan appointment process.

The RTI Act should have been implemented in letter and spirit. Understanding the exceptions from experience can reduce corruption. Frankly, the government should agree to amend or repeal Section 8(1)(j) to prioritise public interest, enabling crucial disclosures such as those on public servant conduct or beneficiary data, especially for social audits. But can this be done? Especially when political regimes are solely interested in winning elections and completely forget about ‘governance’. They even manage elections, election officers, and commissioners, where the foundation is laid even before government appointments.

Governments know in advance that vacancies will arise. They also know that new appointments come with retirement dates. Yet, they don’t bother to select new faces. They create loopholes, incompetence, and shortcomings to increase litigation, leading to court proceedings, and cases reach the Supreme Court. Appointments are made based on pending cases and their tenures are somehow completed. Filling vacancies in a timely manner, modernising record keeping systems, punishing non-compliance, and reducing backlogs by simplifying the appeals process are all possible, and they are aware of them. But the will is lacking. Learning from successful models like Gujarat and Maharashtra can guide these reforms.

To protect RTI users, it is essential to strengthen and enforce the Whistleblower Protection Act (2014), enhance witness and applicant protection, and ensure active monitoring of threats to transparency seekers. Implement public education campaigns on RTI rights, especially in rural areas. Simplify application procedures, provide multilingual options, make offline options available, and promote digital literacy tools. Genuine RTI applicants have only a nine per cent chance of accessing information. Most Public Information Officers are only willing to provide information when they are duty-conscious. Success, then, depends on the work of the officers handling the first appeal. Active support from the First Appellate Authority within public authorities will certainly help genuine applicants. The percentage of those who reach the second appeal again depends on the rule of law and vested interests committed to supporting good governance. Some basic standards or filters should be implemented for malicious RTI applications, such as requiring a declaration of relevance or discouraging repeated applications that burden the system.

In conclusion, RTI has had a profound impact, whether in exposing corruption, empowering citizens, or encouraging democratic oversight. But increasing amendments, institutional weaknesses, and bureaucratic inertia have jeopardized its promise. Recent events, both encouraging and worrying, highlight the ongoing struggle between transparency and control.

Reviving the spirit of RTI requires a multifaceted approach. These include legal amendments, institutional reforms, public education, and political commitment. If revitalised, RTI can regain its role as a democratic bulwark, ensuring that governance remains of the people, by the people, and for the people. Democracy cannot exist without genuine voting rights. Governance is impossible with corruption.

M Sridhar Acharyulu is a former Central Information Commissioner and currently a Professor at the School of Law, Mahindra University, Hyderabad

Views expressed are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect those of Down To Earth