The controversy over a police officer’s letter to the Banga Bhawan in Delhi, calling Bengali a ‘Bangladeshi language’, has bowled into a full-fledged political fracas.

“Translation of documents containing text written in Bangladeshi language-regarding,” the subject line of Amit Dutt’s letter read.

“The identification documents contain texts written in Bangladeshi and are needed to be translated to Hindi and English. Now, for the investigation to proceed further, it is requested that an official translator/interpreter proficient in Bangladeshi national language may kindly be provided for the aforesaid purpose…” the letter reads after talking about eight people arrested on suspicion of being Bangladeshi nationals and documents recovered from them.

Political leaders from the Trinamool Congress, led by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, have slammed the letter as an attempt to conflate Indian Bengalis with Bangladeshis. They have also called out the terming of Bengali, the second most spoken language in India and one of the 22 languages recognised under the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, as the ‘Bangladeshi National Language’.

Bharatiya Janata Party Leader Amit Malviya responded to Banerjee’s attack by saying the letter alluded to the fact that the language spoken in Bangladesh was different from the one spoke in West Bengal, before going into an explanation about Bengali dialects.

Others though have pointed out that the letter was talking about script, which is common for all versions of Bengali, whether eastern or western.

But even as the tumult over the incident plays out, what actually are the dialects of Bengali or Bangla? And what distinguishes and yet unites them?

Bengali, or Bangla, is an Indo-Aryan language of the Indo-European family of languages. “With its sister speech Assamese, Bengali forms the easternmost language in the IE. linguistic area, just as the Celtic Irish and the Germanic Icelandic are the westernmost. It has been in existence as an independent and characterised language, or, rather, as a distinct dialect group, for nearly ten centuries,” the late linguist Suniti Kumar Chhatterji writes in his 1926 work, The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language.

Poet, linguist, archaeologist, anthropologist and researcher, Bijay Chandra Majumdar, notes the geographical spread of Bengali in his 1920 work, The history of the Bengali language.

“If we exclude the recently acquired district of Darjeeling from the political map of Bengal, the entire indigenous population of the Presidency of Bengal will be found to be wholly Bengali-speaking,” he writes.

Majumdar then adds, “The district of Sylhet to the north of the Chittagong Division and the district of Manbhum to the west of the Burdwan Division, though falling outside the Presidency of Bengal, are but Bengali-speaking tracts and nearly three million souls live in those two districts. By eliminating the exotic elements from the Bengali-speaking areas indicated above, we get a population of not less than fifty million that has Bengali for its mother-tongue.”

According to him, “it is quite an interesting history how Bengali was evolved, and how it became the dominating speech of various tribes and races who were once keen in maintaining their tribal integrity by living apart from one another, over the vast area of eighty thousand square miles”.

According to Chhatterji, “The lndo-Aryan speech thus took over a thousand years to be transformed into Bengali, after it came to Bengal during the first MIA. period (roughly, 400 B.C.-900 A.C).”

Given the huge geographical expanse, Bengali naturally has dialectical differences.

Majumdar describes it best in The history of the Bengali language, when he says that “The hilly accent of Manbhum, the nasal twang of Bankura and Burdwan, the drawl of Central Bengal, which becomes very much marked in the slow and lazy utterance of words by women, and the rapid wavy swing with which the words are uttered in quick succession in East Bengal may to a great extent be explained by climatic conditions as well as by the social life of ease or difficulty; but the influence of the tribes of different localities among whom the speakers of the Bengali language had to place themselves, must not be either minimised or ignored.”

So, what are the dialects of Bengali?

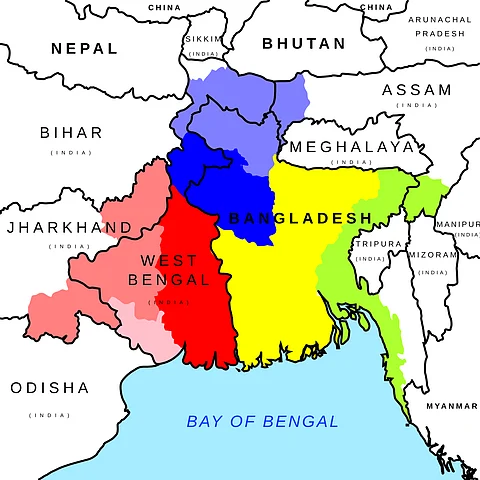

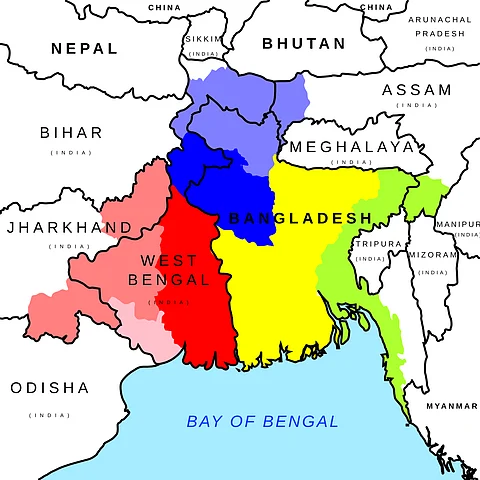

In his 1921 paper, Bengali Phonetics, Chhatterji divides Bengali dialects into four main groups—Western, North Central, Northern, and Eastern (with a SouthEastern sub-group).

“The morphological differences between the four groups of dialects are slight, except in the case of the South-Eastern sub-group; but considerable divergences exist in sounds and phonology,” he says.

But, adds Chhatterji, the differences between the dialects “are not so great as to create mutual unintelligibility among speakers of Bengali in different parts of the country, except, perhaps, in the extreme east and south-east”.

In The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language, he gives a more detailed explanation of the dialectical classification: “The dialects of Bengali fall into four main classes, agreeing with the four ancient divisions of the country: Radha; Pundra or Varendra; Vanga; and Kamarupa.”

These names are derived from the four ancient tribes that inhabited the four tracts that made up undivided Bengal.

“Bengal originally did not form one country and one nation. The Ganges (Padma or Padda) with its branch the Bhagirathi or Hugli and the Brahmaputra divide the country into four tracts, in which dwelt, several hundred years before Christ, at a time when the riverain system of the country must have been a great deal different from the present one, the tribes of the Pundras (in North Central Bengal, roughly in the tract bounded by the Ganges to the south, and the Karatoya in the east), the Vangas (in Bengal east of the Brahmaputra and north of the Padma), and the Radhas and to their south the Suhmas (west of the Hugli). A great deal of the delta was marshy and uninhabitable in the early period of Bengal history. The above four tribes, Pundra, Vanga, Radha and Suhma, were the important ones, who gave their names to the various tracts they inhabited,” notes Chhatterji.

The Rarh region, today divided between Jharkhand and West Bengal, is often identified with the ancient Gangaridai or Radha region of the Bengal delta in Graeco-Roman sources. It today consists of Murshidabad, Birbhum, Bankura, Purba Bardhaman, Paschim Bardhaman, Purba Medinipur, and Paschim Medinipur, besides parts of Jharkhand. It is home to the Rarhi dialect.

The Pundra or Varindra region consists of present-day Rajshahi and Rangpur Divisions in Bangladesh, as well as the West Dinajpur district in West Bengal. This region is home to the Rangpuri dialect.

The Vanga region covers most of today’s south and southeast Bangladesh. The Suhma territory was centred around the ancient port of Tamluk, today in Purba Medinipur district in West Bengal.

According to Chhatterji, the Radha and Varendra, and Kamarupa (to some extent) have points of similarity which are absent in Vanga. “…and the extreme Eastern forms of the Vanga speech, in Sylhet, Kaehar, Tippera, Noakhali and Chittagong, have developed some phonetic and morphological characteristics which are foreign to the other groups.”

Chhatterji notes the dialectical divergences from the western to the eastern ends of Bengal, driven in part, by the languages that were their neighbours.

“The differences in pronunciation and stress, as well as in general enunciation and grammar, which are observable in the Bengali of a Manbhum peasant, and in that of one from Maimansing, are certainly connected with the fact that one is mainly Kol (or mixed Kol and Dravidian), and the other modified Bodo (Tibeto-Burman), by origin.”

Bengali literature uses the Gaudiya or West Central Bengali, writes Chhatterji. “The literary language has all the pan-Bengali characteristics, but sometimes it leans to one dialect and sometimes to another, although its basis is ‘Gaudiya’ or Typical West Central Bengali.”

Of course, the importance of the city of Calcutta/Kolkata cannot be denied. Chhatterji writes about this in The Origin…:

“The speech of the upper classes in the western part of the Delta and in Eastern Radha gave the literary language to Bengal, and now the educated colloquial of this tract, especially of the cities of Nadiya and Calcutta, has become the standard one for Bengali, having come to the position which educated Southern English now occupies in Great Britain and Ireland.”