Depopulation v degrowth

There has been a slight change in the political discourse on India's population woes. Population control has been India's professed national policy, with the two-child norm being the default template to implement it. However, since the 1970s, political leaders have refrained from making population control an electoral issue. Prime Minister Narendra Modi breached this lakshman rekha in 2019. In his Independence Day speech, Modi said population explosion was a threat to the country's present and future. He termed small households as “role models” and that controlling the family size was an “expression of patriotism and love for nation”.

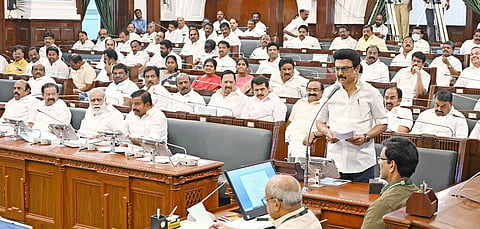

Of late, there has been a growing call from various political heads in the government to increase the country’s population. India is no doubt experiencing a steep decline in population growth, with fertility rate dipping from five in the 1970s to two in 2023, as per the UN World Population Prospects 2024. This is below the replacement level of 2.1. In March this year, Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Nara Chandrababu Naidu said at a workshop on “population dynamics and development” that India needed to move from population control to “population management”, as the situation has changed. Naidu was a votary of two-child norm and population control. That month, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M K Stalin also urged young couples to have more children. The state, with a fertility rate of 1.58, is considered successful in controlling its population growth.

While Stalin’s appeal came in the context of his state losing representation in the Lok Sabha, which is based on population, Naidu’s call was “for maintaining economic stability”. In other words, both underscored the need for more people to not just sustain the society but also to keep fuelling the economy.

The debate is gaining traction across the globe. Arguably, the current world population decline can be compared to the one caused by the bubonic plague of the mid-14th century. That decline was episodic, but this one is happening at a time when humans enjoy maximum lifespan. “What does a planet with fewer people mean for society? It’s a position the modern world hasn’t been in, so we would be crossing a demographic Rubicon,” writes Jared Franz. As an economist, he sees population decline as a negative impact on the economy: less people mean less consumption, ultimately shrinking the economy. It also means fewer working people, reduced tax collection and an ageing society needing more expenditure. J Jeyaranjan, vice chairperson of the Tamil Nadu State Planning Commission, was widely quoted saying, “an ageing population could present an unprecedented challenge for India, one that could place significant financial strain on society.”

“Absent action, younger people will inherit lower economic growth and shoulder the cost of more retirees, while the traditional flow of wealth between generations erodes,” notes McKinsey Global Institute's report “Dependency & Depopulation”.

But some say the declining trend may be good news for the planet and its ecosystems. The rise in human population—no other species has grown and spread so much, and become predatory—has not been planet-friendly. Stephanie Feldstein, population and sustainability director at the Center for Biological Diversity, US, writes in Scientific American, “While many assume population decline would inevitably harm the economy, researchers found that lower fertility rates would not only result in lower emissions by 2055, but a per capita income increase of 10 percent.” She argues, “Population decline is only a threat to an economy based on growth. Shifting to a model based on degrowth and equity alongside lower fertility rates will help fight climate change and increase wealth and well-being.” The U-turn in India’s population discourse just brings into focus this dilemma.