Independence Day 2024: The popular image of the refugee is one of upper caste, upper class people, who have lost everything, says Ravinder Kaur

The idea of citizenship can be traced back to ancient Greece, where ‘civic virtue’ or a ‘good’ citizen was imperative to acquiring the socio-political insignia of a citizen. The narrative behind India’s Independence and Partition has often been dominated by certain voices and experiences, while others remain in the shadows. In our quest for historical truth, we face a critical question: Who gets to tell their story? Whose story deserves to be remembered? Memory is after all, inherently political.

Ravinder Kaur is a historian of contemporary India. She is an Associate Professor of Modern South Asian Studies at the University of Copenhagen. Her ethnographic focus is broadly on decolonisation, state formation, and the making of modern citizenship, which is the focus of her first book Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi (2007, 2018).

On India’s 78th Independence Day, in a conversation with Down to Earth, Kaur talks about the woefully caste blind narrative around the Partition and the politics behind the invisibility of Dalits and lower caste communities in India.

Edited excerpts:

Sohini Roy (SR): What would you say is the nature of caste in India today and how has that changed over the decades?

Ravinder Kaur (RK): I think the first thing that is very clear is that caste has become mainstream, that it is not an add on or an extra thing. It is recognised that in order to understand how the society functions or has been functioning over thousands of years, you need to understand how caste power dynamics work. There is also an increasing, more forthright expression of not being apologetic about it and asking for rights which are due to everyone. So at least, I have seen in the academic discourse, in the political discourse, that caste has become a very accepted and mainstream idea.

SR: Would you say there was a discomfort around the idea of caste earlier?

RK: If I look back into my own work which I was doing on Partition, and this was almost around 25 years ago, there were not many ways that one could speak about the marginalised sections of society. I think a clear example of that is how one could speak about the term ‘Harijan’ for instance and that is in the 1940s and 50s, in the official and unofficial discourses that this is how you would address these communities. So, I think that changed quite a lot over the last several decades. When one speaks about Bahujans, about Dalits — that is a very different kind of political discourse that we are talking about and it is also about claiming one’s own agency which has been primarily missing, if you look back into the 20th century discourses.

SR: What role did the state play in discriminating against lower castes during the Partition — were there specific regulations or policies that were enacted?

RK: I think in order to get here, I should perhaps tell you how I got into working on caste as such. I was doing my ethnographic work in Delhi, and this is the city I was born and brought up in and I know it literally like the back of my hand.

I had chosen residential areas like Kingsway Camp — now it has changed into Mukherjee Nagar — and Derawal Nagar and there are many different localities which have emerged, but also places like Defence Colony, South Extension and the furniture market just behind Lajpat Nagar. These are the old places where refugees were settled after Partition.

So I conducted a large-scale, well not large-scale, but substantial quantitative survey in different colonies. We had actually put a column for caste and religion, just for a general overview of the kind of population we are speaking to.

When we got the results, what was amazing and surprising for me to see was there was no one who had reported any caste, but upper caste.

And that was a puzzle basically. Because you know from the archives and from the census records and everything else that a large section of the population — speaking primarily of Punjab, not Bengal — is marginalised here. So, how do you understand the absence of that population in these spaces, these localities?

It was an eye-opening thing to learn that in 1947, after the resettlement process had been going on, caste is not mentioned in any sort of law or ordinance — caste is basically absent. It is invisible. Nevertheless, there was a caste difference in the new residential localities which were coming up as part of the larger resettlement programme.

But then the question is, how did this happen? Since ordinance or law does not make any mention of any of these variables. You simply are speaking about the people, the refugees who have come in.

And that is something I could finally see had something to do with the compensation policy. To compensate means to make good of what you have lost; in order to lose something you have to have something to begin with. But what if you don’t have anything to begin with? So in the eyes of the state you are not due any compensation. And this is where the class-caste differences begin emerging.

Then, I started digging a bit more, because it simply did not make sense how it is even possible that such a large population is simply absent, from Lajpat Nagar, from Kingsway Camp. That is when I came upon a locality called Regar Pura in Karol Bagh.

What surprised me was I was not aware that a special colony for Harijan refugees was established over there, despite the fact that I was born in Karol Bagh and lived quite a portion of my life there.

Then, the question of resettlement of Dalit refugees comes, because we have records in the archives that there are separate provisions made to settle them in Regar Pura, which was already a settlement from the early 20th century.

So I did my ethnographic field work there as well, and I came into touch with a lot of people who were the original settlers and their descendants.

Karol Bagh is also a commercial area now. So, it has experienced economic prosperity, since real estate value in Delhi has also increased.

Thus, you can see a clear difference between Regar Pura, for instance, where the allocations made to Dalit refugees were very small plots which were not built. So they would be given tarpaulins.

This is all we know from the resettlement policies. And this is where you can start seeing the differentiation.

I also learnt that Nizamuddin, a very expensive, posh residential locality in Delhi, was also a part of the resettlement programme. This is where people who had claimed compensation and said they ‘had lost something’, were settled. So basically, the whole principle of compensation, that if you have lost something, you make good for what you don't have anymore.

SR: Is this the same trajectory that we see in both Punjab and Bengal? Or is this concentrated mainly towards the western front?

RK: No, these were pan-India policies which were made. So it is not specific to Punjab and/or Bengal, but all of India. There has also been a lot of work in the last 10-15 years in Bengal because the state also had a very particular situation with Dalit-Bahujan communities, and that is something worth revisiting as well.

SR: The time that we are talking about, is also a time when there was a lot of fierce debate regarding the issue of caste. Were political reformers aware of the situation on ground? Were they privy to the situation of the Partition, specifically towards the lower castes and were these topics of conversations or contentions between them?

RK: There were certainly people who were trying to raise the question, but I must say that this was raised in a way much different to that of other ‘refugees’ as such.

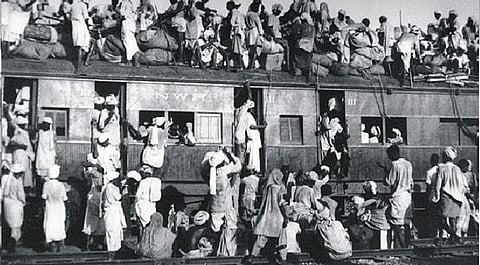

The very image of the refugee is one that is always portrayed as upper caste, upper class people, who have lost things and they have come to the other side, right? So there has always been, in the popular, common view, less focus on the refugees of lower castes and classes. I am talking about literature, movies, popular oral history archives, etc.

There are many reasons for that. First, the invisibility of lower caste groups as such. The way we learn about the marginalised castes in Partition is for example, through police reports and archival materials. Here, you can see there were conflicts between landowners and labourers, where labour tended to be from the marginalised castes. So there was a tussle going on that if we let these labourers go, and keep in mind these are landless labourers, who will do the farm work, the agricultural work?

Also, interestingly marginalised castes were not seen through the prism of Hindus and Muslims. This meant that often, there was a tussle to bring them this way or that way, as if there was not any political agency involved.

The broader umbrella of Hindu-Muslim though is deployed and it often covers upper class, upper caste. But in this instance, marginalised castes are being treated differently and that is under a broader political economy of labour.

SR: Would you say that there are perhaps, successful rehabilitation stories as well, of people who have benefited from the state?

RK: I would say that during my field work, I came across individuals who had done quite well. That is primarily because of some of the affirmative actions which have been put in place, like reservations. That actually began showing results, because I met people who were employed in the government or people who had received education through affirmative action and these were also the social leaders of different communities. So indeed there are success stories.

Though Dalit refugees in Delhi were allocated very small plots of land, ¼ of what was given to upper caste refugees, they also enjoyed some sort of economic prosperity and that is primarily on the ground that real estate prices in Delhi start growing and Regar Pura, which is right next to Karol Bagh, is a large commercial area. So, a lot of people entered leather and many other forms of trade. I have revisited Regar Pura over the years. Many people have sold their properties and moved out.

So, affirmative action and allocation of lands even on a minor scale has helped.

SR: Recently, there have been a lot of attempts at preserving oral history archives which are mainly citizen-led. What are your thoughts on this, since these are mainly projects of memory which are almost personal and sacred in a sense?

RK: I think this is something that I am deeply interested in, that how does collective memory form? Who is the collective actually? And what circulates in the popular domain?

I started doing my doctoral work in the year 2000, almost a quarter of a century ago. At that time, there was a shift going on that we need to listen to stories with specific focus on women; on sexual violence, on the discriminatory practices of recovery and so on and so forth.

So there was a great push at that time to say, “alright we need to go beyond the official archive” and that, I think, was a very important and useful turn. When I started doing my fieldwork, I was looking at people who were around 60 or so, the first generation of original Partition refugees who were coming in and I recorded a lot of interviews across the residential localities that I am talking about.

Over the years, what has happened is there is a push to remember, to record more stories. But what is challenging in this is, how do you not repeat the problem of absence again?

As I already mentioned, I was astounded when I began my work about the absence of marginalised communities and unfortunately that still seems to be the trend. When you listen to voices, people who tell the stories of Partition, and you look at their profile it is still dominated by voices who were primarily the elite.

That sometimes, also has to do with the method, the snowball method: You meet someone and they refer to someone. And you end up reproducing your social circle. It requires a very conscious effort to break that cycle; that there is something missing here that our vision may not be adequate to capture the vastness of the social landscape.

And the reason which not many remark or notice is that is because this is the social world you inhabit and you are completely at home in it.

My parents were refugees too, and I grew up in a locality in Delhi which is also a refugee colony. So you grow up in that milieu and what strikes you is how caste remains deeply invisible still.

In the popular imagination, the figure of the refugee is very much of an upper caste people who had shops, businesses, education, lifestyles, which they had lost. I have barely seen any kind of popular reference to the marginalised communities and this reveals the social world of the producers; whether that content be films, books, documentaries. So you are reproducing your own world in a way. I think as historians it is our job to consciously make a break with that practice and challenge how limiting this might be.

SR: The image of India today, especially how India is branding itself in the 21st century as a ‘Modern India’ — how do you think marginalised communities, such as Dalits fit into that narrative?

RK: That is a very interesting question because we are talking about many things at the same time. When I think of images of modern India, I remember these mass publicity campaigns which have defined our last quarter century or so since the economic reforms, where caste has been a deeply contentious issue: for or against reservations. The late 1980s and 1990s were an era when there was huge conflict over the Mandal Commission. At the same time, caste, as I have already noted, in the political and academic space is more mainstream, right? So many of these movements have been taking place simultaneously.

When I think about images, there is this very globalised imagery in the 1990s — an India which is at home in the world, a global player of upper middle class Indians who travel the world and the world comes to them. But we don’t mention caste. It is seen as an internal matter, which is something we resolve at home.

Publicity campaigns like Incredible India and India Shining, these are particular aesthetics that emerge out of modern, global India. Here too, you will see that it is very much inhabited by people who are upper class and upper caste — who is a worthy representative of India and Indians as such?

So I think in that sense, there are many movements and counter movements taking place at the same time and there is a great debate going on about the caste census. I would again say this moment is one of great churning and there can be many unexpected turns of what we are witnessing as well.