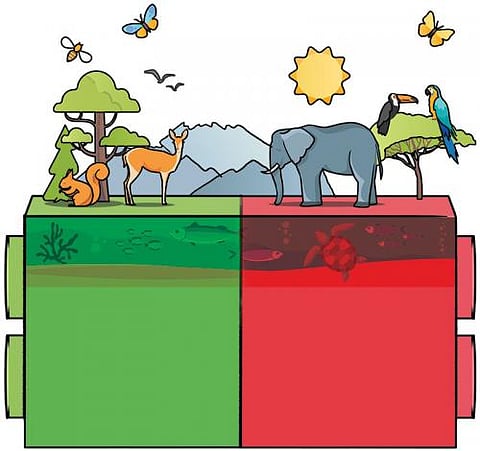

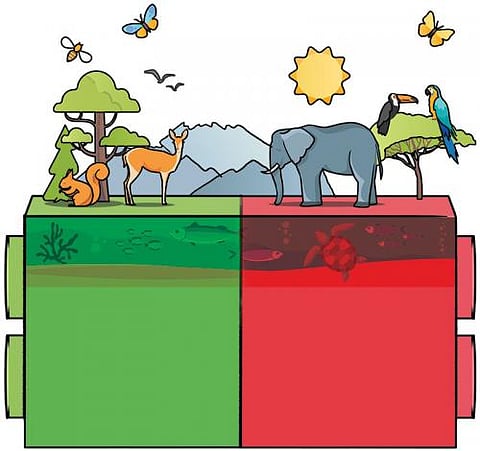

India is home to 7-8 per cent of the recorded global biodiversity. But what is the use of such diversity if the country is unable to protect it, ensure its sustainable use or secure benefits arising from its use for communities that have conserved resources for generations

When it comes to biodiversity, most of the work done in the country is marred by a lack of data and transparency. India ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1994, and nearly a decade later, it passed the Biological Diversity Act, 2002. The Act established a three-tier system, with the National Biodiversity Authority at the Centre, a biodiversity board for each state and biodiversity management committees (BMCs) at the level of local bodies. BMCs are tasked with preparing a People’s Biodiversity Register (PBR) that documents the biodiversity of their respective areas. The committees must ensure sustainable use of resources and that a share in profits accrued from the use reaches local communities.

Until 2016, just 9,700 BMCs were established and only 1,388 PBRs prepared. This fact came to light after Pune-based wildlife enthusiast Chandra Bhal Singh filed a case in the National Green Tribunal. In 2019, the tribunal directed total compliance to this provision of the Biological Diversity Act by January 2020. As of January 2024, there are 277,688 BMCs and 268,031 PBRs.

However, the quality of these bodies and PBRs are questionable (see “Benefit withheld”, Down To Earth, May 16-31, 2022). Communities are not even aware of how they could benefit from biodiversity. Even in cases where agreements have been made on access and benefit sharing, meagre returns have been reported. This could be seen in the case of the Irula tribe’s agreement to provide snake venom to pharmaceutical companies. Data on who has accessed resources and what benefits have been provided to communities are not available publicly. Overall, not much has been done over the past two decades. This must change.

Local communities must be empowered to document biodiversity. The world accepts that communities are adept in protecting the environment in the recently adopted Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF), now called the Biodiversity Plan. The communities hold immense knowledge about their local biodiversity and its use. But this knowledge has been disregarded even when government authorities are involved in documentation. KMGBF also acknowledges the need for funds for conservation of biodiversity.

ACTION POINTS • Empower communities to document their immense knowledge on local biodiversity and its uses • Ensure transparency in access and benefit-sharing agreements made with communities • Funds and budgetary allocation to schemes of environmental protection need greater focus

However, in India, between 2018 and 2024, budget for four Centrally sponsored schemes for environmental protection—National Mission for Green India, Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats, Conservation of Natural Resources and Eco-Systems, and National River Conservation Programme—saw reduced allocation, as per “Envistats—India 2023”, released by the Union Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. The incoming government must ensure action, especially as biodiversity is one of the three triggers of the planetary crisis.

The manifestos of political parties contesting in the 2024 election show some focus on biodiversity. For example, the Indian National Congress’s manifesto reaffirms its “commitment to rapid, inclusive and sustainable development, and to protect its ecosystems, local communities, flora and fauna.” It points out “several departures from the previous policies and important components such as environment protection, forest conservation, biodiversity preservation, coastal zone regulation, wetlands protection and protection of tribal rights.” The Communist Party Of India (Marxist) in its manifesto promises strict regulation for the protection of biodiversity and a repeal of provisions of the Biodiversity Amendment Act, 2023 that permit transfer of knowledge on biodiversity resources to corporations.

The Bharatiya Janata Party mentions biodiversity in the context of sustainable development of hill states, with a promise to work with state governments and local bodies to prepare master plans to maintain biodiversity. It also aims to launch a Green Aravalli Project to preserve the biodiversity of the Aravalli range and combat desertification.

The results of India’s elections would also come as the country revises its National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans, to be submitted to CBD before the 16th Conference of the Parties to the Convention in October 2024. The strength of this document would be a good indicator of the future of India’s biodiversity.

This was first published in the 1-15 June, 2024 print edition of Down To Earth