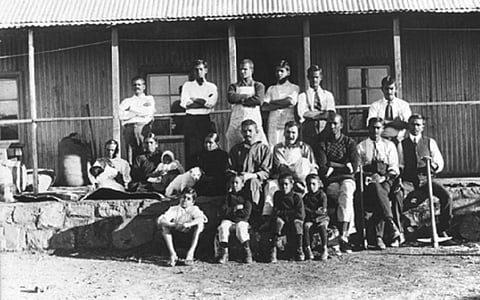

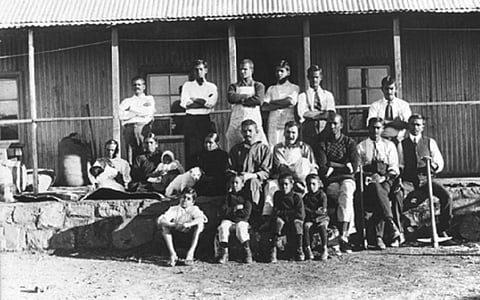

A photo showing Gandhi at Tolstoy Farm. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

As India and the world celebrate another Gandhi birth anniversary, Down To Earth (DTE) delved into the past and present of Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg, where Gandhi first tested the ideas that he was to became world-famous for.

Surendra Bhana, the late South African academic, captured the importance of the farm in the life of Gandhi, South Africa, India and the world in his landmark essay The Tolstoy Farm: Gandhi’s experiment in “Cooperative Commonwealth” (November 1975):

One can say that the Tolstoy Farm was a laboratory for experimenting with problematic issues: diet, nature cure, harmonious living with nature, brahmacharya, and so on. It also proved to be a “training ground” — I must add, incidentally — for his leadership among the people and in the politics of India.

Tolstoy Farm is “located in a southwestern corner of the Johannesburg municipal area, approximately 35 km from Johannesburg, 17 km from Soweto, 7 km from Lenasia and 2 kilometres from the Lawley Station”, notes the portal, www.tolstoyfarm.com.

The site, which fell into disuse during the notorious Apartheid Era (1948-1994), is now being revived as a ‘living monument’ to Gandhian ideals. But can it actually do so in this time, so far removed from Gandhi’s own?

Gandhi set up Tolstoy Farm in 1910 with three goals in mind. He was then supervising the satyagraha by South African Indians in the Transvaal that discriminated against them because of their race.

Bhana notes:

The Tolstoy Farm was in part born out of practical necessity. Funds were running short, morale was sinking, and the movement missed the benefits that might accompany the establishment of a centre where its followers might assemble and coordinate their activities. The Transvaal settlement accommodated all three.

Gandhi’s friend and associate, the Jewish architect Hermann Kallenbach bought ‘Roodepoort No. 49’, an 1,100 acre piece of land from a Johannesburg Town Councillor LV Partridge for £2 000 on May 30, 1910.

“The vision was to create a self-supporting agricultural commune that could provide for basic needs. On a deeper spiritual level, Gandhi was also concerned with trying to develop himself and others in terms of personal growth, spiritual understanding and strength of character through hard labour,” Eric Itzkin, South African historian and author of Gandhi's Johannesburg: Birthplace of Satyagraha, told DTE in a Zoom interview.

He added that while Gandhi himself was not explicit in his writings about connecting with nature through the move to Tolstoy, “certainly there was the sense that one wanted to connect with a simpler, more natural way of life close to the earth and elements, stripping away any kind of unnecessary luxury and getting away from the distractions of urban centres, clearing the mind and soul for deeper reflection and fundamentally connecting with natural forces”.

Tolstoy’s relative remoteness and somewhat natural ambience supported that thinking of Gandhi, something which he shared with Count Leo Tolstoy (after whom Kallenbach christened the settlement) and Henry David Thoreau among others, says Itzkin.

The move to natural settings was not easy. Not least because “to live close with nature implied striking harmonious relations with predatory animals and venomous reptiles that might be roaming on the farm,” Bhana notes.

He also describes a humorous instance where Kallenbach tried to “befriend” a snake. “…but as he well knew, and as Gandhi pointed out to him, there was little love and much fear in the relationship,” notes Bhana.

“At least he tried to cultivate an attitude of living with nature rather than obliterate it or fight it,” Itzkin said.

By all accounts, Tolstoy Farm was a place of great import, especially to followers of Gandhian philosophy. However, it fell into ruin during Apartheid for obvious reasons.

“Apartheid authorities deliberately suppressed information related to Gandhi. There was no support to any Gandhian structure or institution. Most of such structures were those that were very often in Indian areas like the Phoenix settlement in Durban, kept alive by the Mahtama’s grand daughter, Ela Gandhi,” Fakir Hassen, veteran South African Indian journalist, who has spent the last two decades chronicling the revival of interest in Tolstoy, told DTE from South Africa.

Blacks, Whites, Indians and Coloured people were forced to live in racially-segregated neigbourhoods and settlements as per official apartheid policy.

Hassen narrated how Tolstoy, unlike Phoenix, got minimal support from the South African Indian community.

“I first came across Tolstoy in the 1970s when there were only one man and his wife staying there. Then, I too left for other jobs in Durban. By the time I came back in 1985, the residents of the informal settlements surrounding the farm had cut the trees and dismantled the bricks of the structures. There was only tall grass left, when I returned to the spot and the foundations of an old house could be seen from afar,” he recalled.

It was left to Mohan Hira, an immigrant from India, who personally started clearing the grass at the site in the 1980s and 1990s. “By that time apartheid was gone. I and Hira tried to get in touch with people at all levels of power for support and funding, but nothing fructified,” says Hassen.

But post-1994, diplomatic relations were restored between South Africa and India. The Indian missions took an interest in helping with the restoration of Gandhian heritage in South Africa.

Today, part of the farm has been developed as a ‘Peace Garden’. Fruit trees have been planted again at the site.

“The plan now is to involve the local community. Since Tolstoy is located at an isolated location, the local residents, especially women, must have a stake in the monument. Indeed, they can be taught Gandhi ji’s ideals of self-sufficiency and self-reliance. This way, Tolstoy will not only be protected from further vandalism but also be a living monument to Gandhian ideals,” Hassen said.

He added that there can never be a commune at Tolstoy the way it existed during Gandhi’s time.

“That era is past us now and we must adapt to the changing times over a century later. My main concern is about Tolstoy evincing interest among the South African Indian community. Many of those involved in its revival, including myself, are old now. Today’s new generation of the community does not have much interest in preserving this piece of Gandhian heritage, I am afraid. But we are trying our best,” he said.

“With Tolstoy Farm, there has been some positive mobilisation and work to uplift the place and give it more prominence. It is still a work in progress. It is all the more important to try and uphold these ideas and flag these important sites which carry such a rich history and can give lessons for current problems,” said Itzkin.