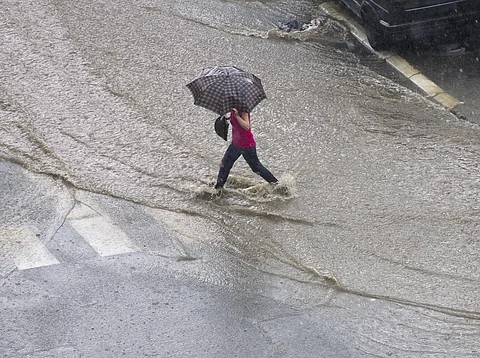

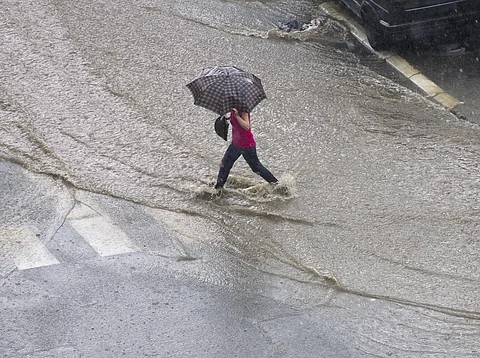

Recent images of water-logged Bengaluru may have led to much surprise, but that may be misplaced: A report nine years ago had flagged that India’s so-called 'Silicon Valley’ could go under even due to moderate rain — the stormwater drains of the Karnataka capital are just not up to the mark.

Authorities ignore this well-known reality and fail to prevent the disaster that results in inundation of homes and roads, power cuts and heavy traffic and sometimes even death.

The Bengaluru Urban district received 79.2 millimetres (mm) of rainfall on September 4 and September 5 against the average of 4.5 mm — recording a 1,660 per cent excess, Down to Earth previously reported.

This year’s rainfall in August was at 370 mm, almost nearing the record of 387.1 mm. So far, one death has been reported in 2022.

Localities in southeast Bengaluru, such as — Bellandur, Marathahalli, Sarjapura Road and others around the Outer Ring Road area — have been at the receiving end of excessive flood.

Unlike the rest of Bengaluru, at an elevation of 3,020 feet, these areas are relatively flatter and have been at the epicentre of rapid development.

That the faulty stormwater drainage system is at the core of the problem is known to all.

The Karnataka State Action Plan on Climate Change that was prepared in 2013 and accepted by the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoE&FCC) in 2015 clearly states the following:

Strom water drains are unable to deal with water from moderately heavy rainfalls, while climate change may lead to greater precipitation in shorter intervals than previously encountered.

In line with the National Action Plan on Climate Change released in 2008, the Union government directed state governments to put together state action plans on climate change (SAPCC).

The SAPCC recommended the following:

SAPCC suggests rainwater harvesting to reduce the amount of water that accumulates in stormwater drain run-offs and the accompanying problems.

Some 0.017 billion residential properties in Bengaluru have installed rainwater harvesting systems and fines worth three lakh crore were collected in 2021, for not harvesting the mandated amount of water, according to the BWSSB.

Surprisingly, residents of the Rainbow Drive layout, one of the areas most-affected by the flood recently, are diligently managing water through rainwater harvesting and their own sewage treatment plant.

Still, the residents fell victim to the stormwater drain outside their immediate vicinity. Instead of carrying the excess water to the nearby lake, the water from the drain landed at their gates, Scroll reported.

The SAPCC had also suggested the following solutions to monitor the drainage system closely:

While the SAPCC talks about urban flooding, a lot goes unmentioned and could be added.

M Balasubramanian from the Institute for Social and Economic Change in Bengaluru, who authored a chapter in Karnataka’s soon to be updated SAPCC on vulnerable communities, told Down To Earth:

Given that poor slums were badly affected in the current floods, the policy can also include an estimation of how much losses and damages are incurred every year due to urban flooding.

For example, an estimate of how much road and infrastructure damage costs every year and how much property is lost every year can be included in the SAPCC to enable the state government to devise contingency plans, Balasubramanian added.

The increasing frequency of floods due to climate change will add to these losses and increase the gap in funding, he said.

The update of Karnataka’s action plan is awaiting approval at the MoE&FCC, along with several other states’ climate action plans, as they have to be revised and approved every five years.

The action plan is merely words on paper that are not referred to by the government while formulating policies, said Leo Saldanha, a Bengaluru-based environmental activist. Walking the talk on this matter will change the impending flooding situation every year, not these empty plans, he added.