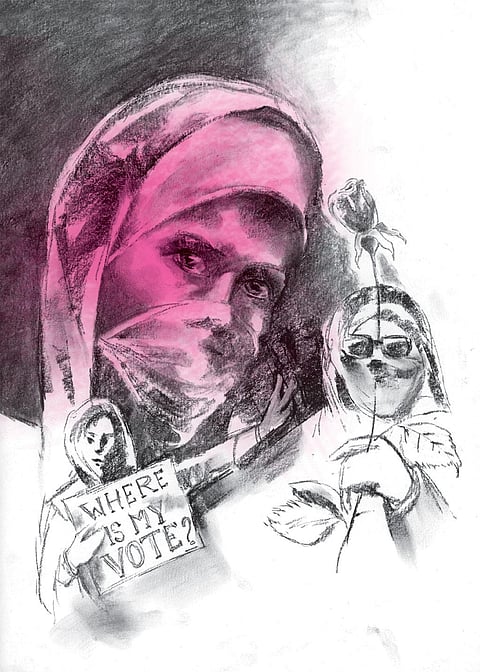

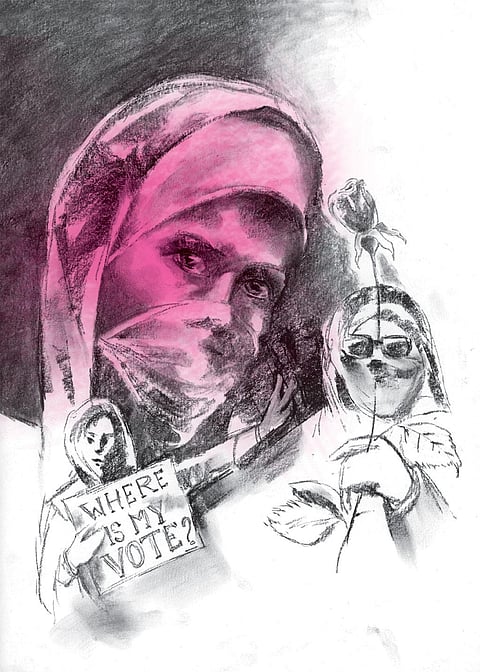

When the east European youth of the 1980s were struggling against communist authoritarian regimes, they valorised the idea of a democratic space as a horizontal self-organised public sphere that could limit the power of the state. The democratic awakenings of the youth around the Middle East from 2009 to 2012 demonstrated once again that new social movements could help provide the independent space that is needed. What united Tunisian and Egyptian youth in their democratic uprisings, as was also the case with the Iranian youth, was freedom from interference and a struggle against the concentration of arbitrary power. For those young Egyptians, Tunisians and Iranians who gathered for several months on the streets of Cairo, Tunis and Tehran, freedom meant putting an end to the unjust accumulation of power and to demand their governments to be based on public accountability and popular sovereignty.

Though the Arab Spring did not put an end to the process of re-colonisation of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), it is certain that the fall of long-time dictators like Ben Ali, Mubarak and Gaddafi, accompanied by the rise of new civic actors and new social movements around the MENA region, represented a series of encouraging signs that a process of democratisation was possible and ideas of popular sovereignty and the rule of law could be taking hold. Today, seven years on, the Middle East is in tatters and the short period of hope and revolutionary ideals has been followed by new forms of authoritarianism and denial of civil liberties. It is clear that the result of the popular protests has been nothing but chaos, leading either to long-term wars (as in Syria), sectarian conflicts (as in Yemen) or increased repression (as in Egypt). As for Libya, seven years after the capture and execution of Muammer al- Gaddafi, the country resembles a failed state that has plunged into a dangerous unrest.

Talking about the Arab Spring, it would be certainly more correct to talk about “uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa” instead of using the word ”Intifadat al-Arabiya” (Arab uprisings), for the very good reason that we also had an “Intifada al Iraniya” (an Iranian uprising). In all and for all, we can say that the extraordinary uprisings in the Arab world that began in early 2011 had a Persian precursor in 2009, which more than any other civil uprising in this region of the world remains an unfinished project. There are many ways to interpret the Persian Spring of 2009. The young Iranian twitter fans see a social media revolution, the Iranian reformists see a reformist imperative in the Islamic Republic at its core, and Iranian human rights groups see a backlash against routine abuses of the Iranian regime.

But, actually there were a full range of different “drivers of change” involved in bringing about what is called the Green Movement of 2009. Considering the complexities of Iranian society and politics, it is important to highlight the fact that the Green Movement of 2009 was essentially a youth movement, which found deep roots in the principles of non-violence. Without going back too far, we can say that in the last 30 years, Iran has been on the course of a major political and societal evolution since the increasingly young population has become more educated, secular and liberal. As a result, this generational gap divided the Iranian society between essentially money-making and powerful conservatives and young rebels without cause.

Iran became a society divided between Donald Trumps and James Deans. Therefore, it is not strange that the Iranian youth has been at the forefront of support for the nuclear deal because they have suffered the most from unemployment and the Iranian currency devaluation as a result of the sanctions. Whether as internet users or spontaneous demonstrators, the young population of Iran, which represents today more than 60 per cent of the 80 million Iranians around the country, are well educated and believe in gradual change of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Interestingly, over half of Iranians between the ages of 18-25 attend some form of higher education and more than 60 per cent of the entries in the Iranian universities are women. Also, Iranian youngsters are by far the highest per capita users of the internet in the Middle East. The civic rebellion of 2009 was arguably a manifestation of such changing attitudes that have been slowly emerging among Iran’s overall young population. These attitudes opened up the options of non-violent discontent among the Iranian youth. This was Iran’s Gandhian moment. If there is still an element of non-violence playing in the social attitude of young Iranians, it is about overcoming the ideologisation of politics.

However, two main elements are still missing in such a potential of rebellion: a moral leadership and a determined strategy. In 2009, the movement started strong but soon faced a violent crackdown by the Iranian regime and lost its momentum due to the state’s incarceration of protestors and key figures. As a matter of fact, the youth movement of 2009 in Iran was unable to enlist the support of key segments of the Iranian economy, which would have included major industries, transportation and worker unions, government employees, bazaar merchants, and most importantly, oil workers. Certainly, had the movement gained the support of such powerful economic groups, they would have financially weakened the state and possibly made them more inclined to negotiate or engage in some sort of talks like what happened in Poland with the Solidarnosc.

However, the recent wave of social unrest in Iran in December 2017 was more in terms of a shared adherence of the Iranian youth to values of non-violent reforms that are fully compatible with the transformative dynamic of the Iranian civil society. Though it is still too early to speculate about what this transformative dynamic might hold for the future of Iran, one can surely say that the spread of non-violent strategies in the Iranian society would unquestionably be a positive model for the future empowerment of civil societies in the Middle East—this time, of course, free of the shadows of theological revolutions or secular military coup d’états.

(The author is a political philosopher and teaches at the Jindal Global University, Delhi)

(This story was first published in the 1-15th May issue of Down To Earth under the headline 'Post spring outpourings'.)