Earth’s most recent geomagnetic reversal — a phenomenon where the planet's overall magnetic field flips — took at least 22,000 years to complete. This is more than twice than previously thought, according to a study by University of Wisconsin-Madison.

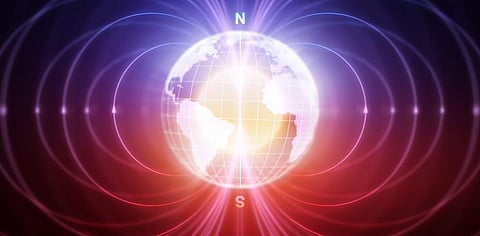

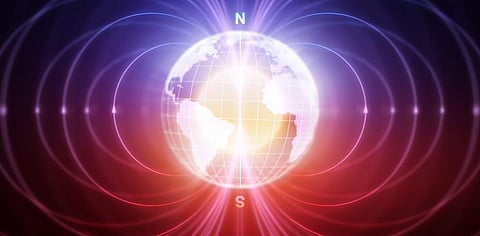

The magnetic field, which protects the Earth from potentially dangerous solar radiation, last flipped some 770,000 years ago and is named Matuyama-Brunhes after the scientists who discovered it, according to the journal Science Advances.

While the final event lasted 4,000 years, it was, however, preceded by another 18,000 years due to an extended period of instability, which included temporary, partial reversals.

The Matuyama-Brunhes took more than twice as long to flip, while all reversals generally wrap up within 9,000 years, showed the new analysis based on advances in measurement capabilities and a global survey of lava flows, ocean sediments and Antarctic ice cores.

The liquid layer of the Earth called the outer core is responsible for its magnetic field. As Earth spins on its axis, the iron inside the liquid outer core moves around and creates a field.

Reversals of the magnetic field are recorded in the rocks in a phenomenon called rock magnetism. Many rocks contain iron-bearing minerals that act as tiny magnets. As magma or lava cool, these minerals align with the magnetic field preserving its position and form rocks.

The record can be pieced together to understand the history of magnetic fields going back millions of years. The record has been clearest for Matuyama-Brunhes, according to the study.

“Lava flows are ideal recorders of the magnetic field. They have a lot of iron-bearing minerals, and when they cool, they lock in the direction of the field,” says Singer. “But it’s a spotty record. No volcanoes are erupting continuously. So we’re relying on careful field work to identify the right records.”

For the analysis, geologist Brad Singer and his team from the varsity combined magnetic readings and radioisotope dating lava flow samples from Chile, Tahiti, Hawaii, the Caribbean and the Canary Islands and recreated the magnetic field over a span of about 70,000 years centered on the Matuyama-Brunhes reversal.

To date these lava flows, they relied on measuring the argon produced from radioactive decay of potassium in the rocks. They, further, confirmed the data with the magnetic readings from the seafloor, which provides a more continuous but less precise source of data than lava rocks.

The team also used Antarctic ice cores to track the deposition of beryllium — produced by cosmic radiation colliding with the atmosphere. During a magnetic field reversal, it weakens and allows more radiation to strike the atmosphere, producing more beryllium.

“I’ve been working on this problem for 25 years... And now we have a richer record and better-dated record of this last reversal than ever before,” said Singer.

While Earth’s magnetic field looks steady, it dramatically shifts and reverses its polarity every several hundred thousand years. Its strength has decreased in strength about five per cent each century, since the time records began.

The magnetic North Pole is currently careening toward Siberia, which recently forced the Global Positioning System that underlies modern navigation to update its software sooner than expected to account for the shift.

A reversing field might significantly affect navigation and satellite and terrestrial communication, but society would have generations to adapt to a lengthy period of magnetic instability, suggests the study.