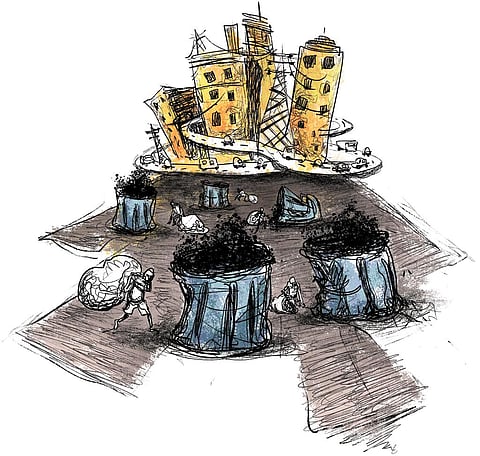

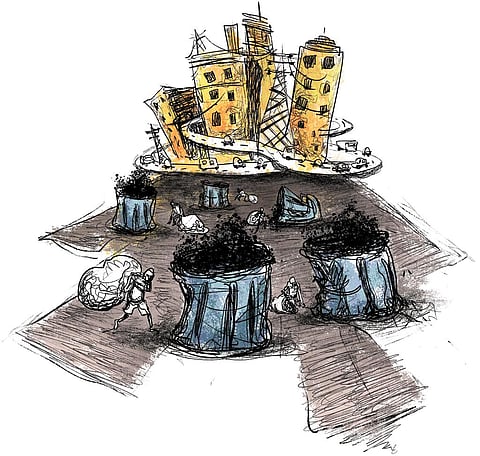

India produces about 5.31 million tonnes of waste each year and is facing an unprecedented solid waste management crisis. Coupled with an upward trend in industrialisation, rural migration, spending and an increasing propensity for capitalist consumption, the amount of waste generated in India will continue to increase rapidly with time. Till now, India has managed to collect, segregate and dispose waste largely due to the efforts of waste pickers, who form the backbone of this sector. Unfortunately, their profession remains unrecognised under the law in India.

Waste picking is one of the most accessible means of livelihood for the impoverished in India as it requires minimal skills, knowledge or capital investment. As per the definition adopted by the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016, the term “waste picker” has been defined as: “A person or groups of persons informally engaged in collection and recovery of reusable and recyclable solid waste from the source of waste generation… for sale to recyclers directly or through intermediaries to earn their livelihood.”

It is estimated that waste pickers are responsible for recycling almost 20 per cent of the country’s wastes. A study conducted in 2016 by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing in Delhi, a non-profit, revealed that over 76 per cent of waste pickers interviewed sold their waste to formal buyers making them vital to the industry.

The cost of non-recognition

Since waste pickers are not recognised under Indian laws, they face numerous forms of discrimination. Their basic rights are repeatedly violated disregarding their contribution to society. Waste pickers often targeted and harassed by police and anti-social elements as they are seen as vagrants and thieves. Waste pickers are not legally permitted by state municipalities to collect, segregate and sell waste from garbage dumps across the country, and they are deemed to be committing theft under the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

Supriya Routh, in her book, Enhancing Capabilities Through Labour Law: Informal Workers in India, found that most waste pickers who were interviewed for a study in 2011 had been taken into police custody at least once in their lives and had been booked for petty cases. Routh’s study also found that non-recognition had made migrant waste pickers ineligible for government schemes, in addition to facing insurmountable difficulties in obtaining ration cards, electricity and water facilities. This had a significant negative impact on their standard of living as well as on their mental and physical wellbeing.

Due to constant exposure to putrid and hazardous wastes, waste pickers are vulnerable to skin diseases, musculo-skeletal ailments, respiratory disorders, cuts and needle wounds. But due to non-recognition, waste pickers are often excluded from various government health schemes.

Moreover, their jobs are highly insecure. A 2011 study by Chintan, a non-profit advocating for the rights of waste pickers in Delhi, found that after the Municipal Corporation of Delhi privatised waste collection, approximately 50 per cent of waste pickers lost their jobs or experienced a drastic fall in their incomes. Waste pickers previously had an informal sharing system that allowed a large number of them to collect waste within the same area. However, post-privatisation, fewer people were able to earn a living from the same volume of waste. Similarly, a study conducted in Punjab in 2016 also found that privatisation had a negative impact on their access to wastes as well as their capacity to earn a livelihood.

Wanted: a comprehensive law

The need of the hour is the creation of a waste picker welfare law that recognises waste picking as a genuine profession and ensures that the rights and needs of waste pickers are recognised and addressed as legal obligations, instead of state largess. A law would also considerably aid to reduce the insecurity and stigma associated with waste picking. For a welfare law to be comprehensive, it must include:

The author works with the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Bengaluru

(This article was first published in the April 1-15th issue of Down To Earth).