Bizarre, serious, jocular

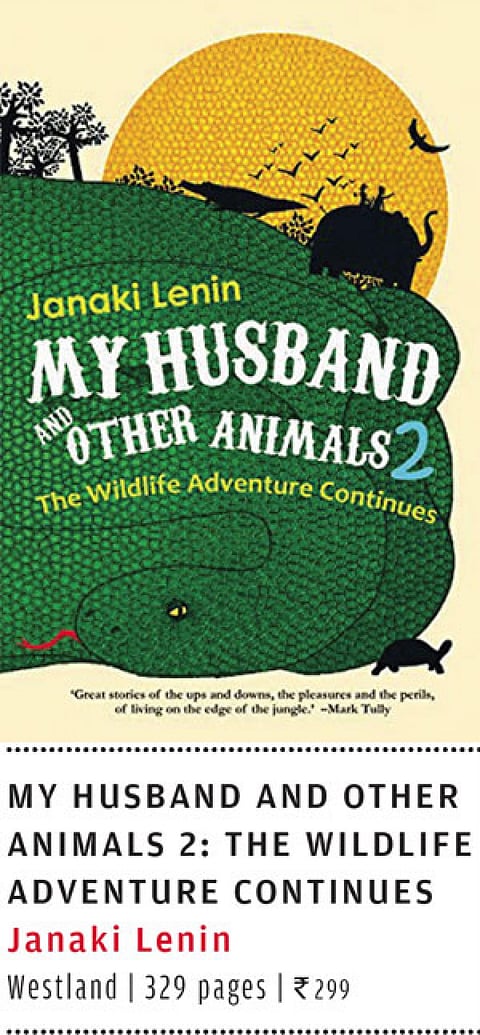

JANAKI LENIN describes her experiences of living with veteran herpetologist, Romulus Whitaker, in this sequel My husband and other animals 2: The wildlife adventure continues. Through these 81 stories, we not only learn about unknown facets about mammals, reptiles, birds, amphibians and fish, but also about what it is to be human. Each story is peppered with astute observations, logical inquiry and deduction, light-hearted humour, serious insights and most of all, overarching curiosity about the world around us and the secrets that it seemingly hides.

For instance, did you know that palm civets are crazy about toddy and coffee? Or that humans can “unlearn” their fear of snakes. One of the names of the King Cobra is the Hamadryad, Greek for “nymph of the woods”, given to it by Danish scientist Theodore Edward Cantor for its extraordinary physical beauty. Donkeys can give humans rabid bites. Bull crocodiles are caring fathers. As are male tigers and leopards, contrary to conventional wisdom. Crocodilians can climb well, with the mugger or the marsh crocodile of the Subcontinent leading the pack. Some carnivores are frugivorous too. And Leatherback turtles, the largest in the world, regularly cross oceans.

Some of these stories may sound bizarre, but are, in fact, proof of the keen observational skills of the author. Take for example the two stories on poop. In one, Lenin writes how many animal species, ranging from lagomorphs like hares to dogs to iguanas and pigs eat their own and other species’ faeces since it gives them nutritional supplements or even gut flora.

Lenin also writes on two topics about the human condition. In “Why do Men Rape?” she examines corresponding examples from other animal species and shows that non-human males also rape; these include drakes, ganders, orangutans and bottle nose dolphins. She compares scientific literature on rape and deliberates on the age-old question: is rape about sex and innate behaviour or is it about power and learnt behaviour? She concludes that we cannot take these two exclusively. Rather, rape is a product of both these two phenomena.

In her two stories about homosexuality, Lenin is very clear: homosexuality cannot be against the order of nature. She concludes that there is no one single explanation yet as to why homosexual behaviour evolved in human and non-human species. Some pieces are very dark. For instance, in “The High Price of Sex”, Lenin writes about a male King Cobra killing and nearly devouring his own mate. King Cobras are snake eaters is well-known. Their very scientific name is testament to that: Ophiophagus Hannah, snake eater. But the fact that they can eat each other came as a dark surprise.

There are essays that also show how dangerous working with animals is. Sample this: “One basking croc suddenly woke up to find a human (Rom) almost nose to nose, taking its picture. When it dove under the coracle (boat), the pointy scales on its back rubbed rat-a-tat against the bamboo ribs.”

In the end though, the book is a homage to Rom Whitaker. The book reveals some hitherto unknown facts about his life. Like when he was bitten by a prairie rattlesnake in Texas in 1966, he had to become a lab rat for an experimental treatment called cryotherapy involving ice. Whitaker consequently lost the use of his right index finger. A few years later, cryotherapy was discredited. Or that he gave up his US citizenship and took up Indian citizenship in 1975 to study the fauna of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which were then off-limits to foreign nationals. The book is easy to read, jocular, serious, trivial as well as detailed. Go for it.

|

`Urbanites have poor wildlife understanding'

How different is this book from the earlier one? It's similar to the extent that it's another collection of essays about animals, people, and my husband. To a greater degree, readers influenced the kind of topics I deal with in this second book, so it has a different feel and tone. Do you think more young people in India today think of wildlife conservation as a career? I guess so. While it's nice to see their concern for conservation, there's also another side. Conservation is not just about campaigning for wildlife and habitats. There's a quote that goes something like this: conservation is 95 per cent working with people. And this is what we don't do well. Most of these young people live in cities where they are not only insulated from the real world difficulties of living with wildlife, but they are also unsympathetic towards those whose livelihoods and lives are on the line. Much of their understanding of the issues is shallow. This combination of lack of sympathy and ignorance can make conservation policy and management difficult. Urbanites, in our arrogance, think rural communities are ignorant at best or dangerous at worst to wildlife. They are the soft targets. Many of these rural communities adjust to make space for various species at some cost to themselves. We don't even recognise this, let alone celebrate them. We have to make them equal partners in conservation. Conversely, we don't push hard enough when it comes to forces more powerful than us: politicians and corporate houses. The fight against them is led by local communities in places like Niyamgiri, Kutch, and Arunachal Pradesh. So you can see who the real conservationists are. This is not to tar all of them with the same brush. Some young conservationists fight these difficult battles with deftness and sympathy and better than the earlier generations. What are your future projects? I am working with Rom on his memoir and writing a book on the Irulas and their traditional wildlife knowledge. |