Evidence from an ancient cave site in Israel challenges the idea that early human species were in constant conflict, instead showing shared cultural practices between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals.

A new study of Tinshemet Cave, published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour, has suggested that humans and Neanderthals coexisted peacefully between 80,000 and 130,000 years ago, sharing technology, lifestyles and burial customs.

Researchers found evidence of humans and their extinct relatives, Neanderthals, engaging in formal burial practices. They also used ochre — a natural mineral pigment commonly employed to colour earthenware, household utensils and decorations.

The period between 80,000 and 130,000 years ago, known as the mid-Middle Palaeolithic (mid-MP), witnessed increased human migration from Africa. The findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that humans used Southwest Asia as a corridor for expansion into Asia.

The study also indicated that an improved climate during this period favoured human migration. “During the mid-MP, climatic improvements increased the region’s carrying capacity, leading to demographic expansion and intensified contact between different Homo taxa,” Marion Prévost of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem said in a statement.

Since 2017, researchers have been excavating Tinshemet Cave to determine whether humans and Neanderthals competed for resources, lived as peaceful neighbours, or collaborated.

The cave comprises a terrace and three chambers, with the deepest one now featuring an open chimney. The study found that artefacts dating back 130,000–80,000 years extended across much of the exterior terrace and the first chamber. The second and third chambers lacked evidence of human occupation.

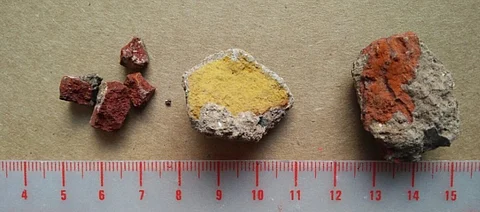

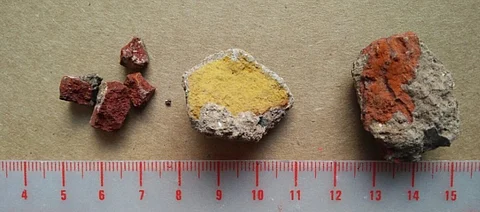

Excavations uncovered 7,500 ochre fragments of different sizes, shapes, textures and colours. Most were red to orange (75.7 per cent), followed by brown (16.7 per cent), yellow (5 per cent) and purple (2.6 per cent). Many of these ochre fragments were found near burials. For example, researchers discovered a 4-5 centimetre chunk of red ochre between the legs of an individual buried in the cave.

Additionally, the team uncovered remains of eight taxa of micromammals (small mammals) and large mammals, predominantly ungulates (hoofed mammals). Among the most represented species were aurochs (an extinct European wild ox), equids (such as horses, asses and zebras), Mesopotamian fallow deer and mountain gazelles. The team also found human remains from five individuals.

Furthermore, the study noted similarities in burial practices at Tinshemet Cave and two other prominent MP sites, Skhul Cave and Qafzeh Cave. “All three sites show remarkable similarities in how people disposed of their dead,” the paper stated.

At all three sites, various objects were placed inside graves, including animal remains and chunks of ochre. “The mid-MP burials at Tinshemet, Qafzeh and Skhul caves represent the earliest instances of intentional Homo burials, predating the formalised burial practices in Europe and Africa by tens of thousands of years,” the authors wrote. The placement of these artefacts within burial pits may suggest early beliefs in the afterlife.

The researchers also argued that different human groups, including Neanderthals, pre-Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, engaged in meaningful interactions. The extensive use of mineral pigments, particularly ochre, perhaps for body decoration, may have helped define social identities and distinctions among groups.

“Our data show that human connections and population interactions have been fundamental in driving cultural and technological innovations throughout history,” Yossi Zaidner of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem said in a statement.