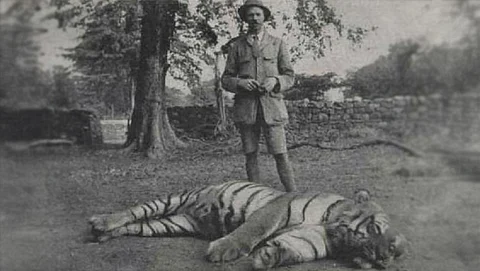

Jim Corbett, known as 'Carpet Sahib' in Kumaon, is a multifaceted figure: a big game hunter, author, and conservationist.

His writings, especially 'Maneaters of Kumaon', offer vivid depictions of India's wildlife and landscapes.

While his hunting exploits saved lives, his later conservation efforts laid the groundwork for wildlife protection, making him a complex figure of his era.

First things first. I have only read Maneaters of Kumaon and The Maneating Leopard of Rudraprayag by Jim Corbett. I have not read Jungle Lore, Tree Tops or My India. Having said that, I have read and re-read the aforesaid books. They are for me, like for millions of others worldwide, a part of childhood memory. A first introduction to India’s jungles and their denizens.

Of course, today, there are a lot of perspectives on Corbett. Or Carpet Sahib as he is called in his native Kumaon. There is Corbett, the Big Game Hunter. Corbett, the author, of course. And Corbett, the conservationist.

But then, who is the real Edward James Corbett? And why is there an almost mythical aura around him?

Perhaps the best explanation to that comes by studying Corbett’s eventful life and times. He was born back in 1875. A time when the Victorian Era was at its peak and Pax Britannia was everywhere. By the time he died 80 years later in 1955, the British Empire was long gone. The story of Corbett is thus the story of these years when he walked this planet.

Corbett was born into a family of Irish stock that served the British Indian government. He was born in Nainital, in the hills of the then colonial United Provinces of British India, now the state of Uttarakhand. His childhood in the hills and jungles of Kumaon were to leave an everlasting impression on his life and work.

Due to his childhood mostly spent outdoors, Corbett knew more about the forests than anyone else. It is something that comes across in his writings too.

Observation. That is the keyword for Corbett. “A big game hunter, a writer and a conservationist, all have one thing in common: keen powers of observation. And Corbett, who was all these three parts, possessed an exemplary ability to observe and describe whatever he saw,” Dharmendra Khandal, who works with Ranthambore-based non-profit Tiger Watch, told Down To Earth (DTE).

As he adds, all those who were associated with the official state machinery in British India, be they military officers or those in the administration, hunted wildlife and wrote about their ‘exploits’. “But the way Corbett described nature in detail and depth was a class apart. He was an encyclopedia in himself about wild India. His books and writings teach us not just about hunting but about the beauty, majesty and grandeur of nature,” says Khandal.

It is something that Ullas Karanth, one of India’s foremost tiger experts, acknowledges. “To me, Corbett’s description of nature in Jungle Lore, natural history and being in the jungle is very interesting.”

For me personally, reading Maneaters of Kumaon or The Maneating Leopard of Rudraprayag is like being in the wilds of Kumaon or Garhwal. There is just me and the tall grass. Or the wooded ravine. Or hilltops, glades, meadows, brooks. And the jungle folk. The kalij pheasant. The porcupine. The jungle babbler. Kakar. Sambar. Goral. Chital. Himalayan Black Bear. And of course, the leopard and the tiger. Everything plays out beautifully before you like you are right in front of them.

Of course, any word about Corbett’s writing would be incomplete without describing about the maneater tigers and leopards whom he hunted.

Reading Corbett often feels like reading a detective story. How a case of a man-eater is brought before him. And how he studies the case, separates the wheat from the chaff and ultimately catches the culprit. Almost like a Sherlock of the animal world.

Corbett’s hunts of ‘problem’ tigers and leopards also saved countless lives in Kumaon and Garhwal. I remember the case of the Thak maneater, a tigress he hunted in around 1938. The animal had become a threat for countless villages in the Sarda Valley. His effort at eliminating this animal was almost similar to John H Patterson’s killing of two man-eating lions near the Tsavo river in what is today’s Kenya in 1898.

So, Corbett’s astute powers of observation, his writings and of course, his helping the villagers of Kumaon and Garhwal laid the groundwork for his celebrity image. But Corbett did turn conservationist in later life.

“I have always regarded the tiger as a flagship, a bulwark of saving something more important which is the habitat of the tiger. Because you can have the habitat without a tiger but you cannot have a wild tiger without a habitat. Corbett did not emphasise on that. Perhaps it was not necessary in those days. But he did talk about the predicament of the tiger: How it had declined and what may happen if it went. He was one of the first to sound the alarm bells. He also showed the way to a lot of us. He was a pathfinder, a pioneer in that respect. His is a classic case of conversion…of the hunter-naturalist to a conservationist,” M K Ranjitsinh, the architect of the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, told DTE.

But has the image of Corbett the Big Game Hunter overshadowed Corbett the conservationist in any way?

“I would say we must look at Corbett as a man of his times. He was called upon to eliminate ‘problem animals’ and he could take out exactly that animal without the aid of camera traps, DNA or any other modern technology. All courtesy his excellent tracking skills and ability to interpret what the jungle and its residents told him. Having said that, I would also say we need not deify and mythologise him. Neither should his writings be considered the gospel truth. Corbett, in the end, was the sum total of parts and a product of his age,” Khandal says.

For Karanth, Corbett’s peer F W Champion was a true hero, one greater than Corbett. “He was a conservationist. He shot only one tiger when he was DFO because that was required. He was also concerned about their well-being, as can be discerned from his writings.”

For Karanth, even Corbett’s writings are not as important today as they were once upon a time. “That world (of Corbett) is long gone. For those of my generation who were interested in wildlife, Corbett and his works were a good hook. But for today’s generation, with so much resource material, Corbett is not a necessity.”

That does not mean one should not read him. “Of course, one can read him. But with a modern lens. You can read Corbett for entertainment today. But if one is serious about saving tigers, Corbett’s works no longer serve as a beacon,” says Karanth.

Perhaps that is what it comes down to. Corbett appeals to us as he belongs to an India that is long gone. Consigned to the pages of history. Never to come back again. But Corbett, being the perfect chronicler of his age, has preserved its memory well. And in the end, all that matters is memory. Corbett, his works, his life…all are memories today. But very sweet ones at that. Hence the myth of an ordinary man, walking in thick jungles in the darkest of nights, on the lookout for problem tigers and leopards, appeals to us.