International Dog Day is dedicated to “man’s best friend”. It spread from the United States, where the celebration started, to countries worldwide. Today, it is celebrated globally with awareness campaigns and activities focused on dog care and well-being.

Dogs have been companions of humans since times immemorial. They often find space in literature, arts and iconography.

One of Christianity’s greatest saints was depicted for a long time with the head of a dog. The backstory of why this is so provides interesting clues to the how the Greeks and Romans, who first adopted the faith, viewed non-Greeks and non-Romans and were thus called ‘barbarians’.

Christopher is the patron saint of travellers in the Christian tradition. He is revered by several Christian denominations including those in the Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant traditions.

Much of the world knows the story of Christopher carrying the ‘Christ child’. As the website of the Vatican says: “The most popular image of St. Christopher depicts him as a huge, bearded man, carrying the Christ-Child on his shoulders as he wades across a river. The Child Jesus is holding the world in His hands like a ball. This image dates back to one of the most famous biographies of those who were martyred on July 25th in Samos, in Lycia.”

The legend goes that Christopher’s real name was ‘Reprobus’ (‘the reprobate’). He was a ‘barbarian’ and lived during the time of the Roman Empire.

Reprobus was a giant of a man and wanted to serve the strongest king in the world. After serving one such king, he found the Devil was stronger. So, he served the Devil. But Devil considered Jesus Christ to be stronger than him. Christopher thus went looking for Christ. The Vatican picks up the story.

“A hermit advised him to build a hut near a river that flooded dangerously and to use his great strength and stature to assist travelers cross to the other side. One day he heard a child’s voice asking for help to cross the river. Reprobus put the child on his shoulders and began to wade through the rapidly rising water. But the further he went into the river, the heavier the child became. It was only with great effort that he managed to reach the opposite shore. There the child revealed his true identity as Jesus. The weight that Reprobus (now Christopher) had been carrying was that of the whole world, saved by the blood of Christ. This legend, in addition to inspiring western iconography, has made St Christopher patron of boatmen, pilgrims and travelers.”

Reprobus thus became ‘Christopher’ or the ‘Christ bearer’.

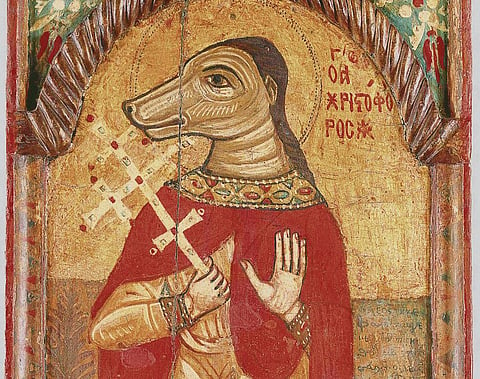

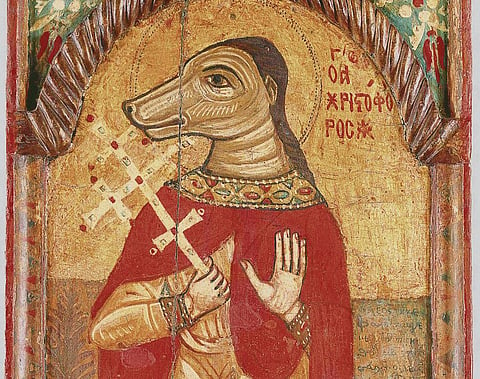

But there is another image of St Christopher. For several centuries, he was depicted in the Eastern Orthodox Church (which split from the Roman Catholic Church after the Great Schism of 1054) with the head of a dog.

So, what is the story behind this? Irish scholar David Woods in his work The Origin of the Cult of St. Christopher, says, “St. Christopher was a member of the north African tribe of the Marmaritae. He was captured by Roman forces during the emperor Diocletian’s campaign against the Marmaritae in late 301/early 302 and was transported for service in a Roman garrison in or near Antioch in Syria. He was baptised by the refugee bishop Peter of Alexandria and was martyred on 9 July 308.”

According to Woods, “The identification of St. Christopher as a member of the tribe of the Marmaritae is vital to the correct understanding of a passage which has caused more problems than most, the description of his nativeland present in all the earliest surviving accounts of his martyrdom, both Greek and Latin, according to which he came from a land of cannibals and dog-headed peoples.”

The concept of ‘dog-headed’ cynocephali was an abiding one in various parts of the ancient world, including Europe.

One of the first people to write about these humans with the heads of dogs was the Greek physician Ctesias, who apparently encountered them on a trip to the mountains of India around 400 B.C. “On these mountains there live men with the head of a dog, whose clothing is the skin of wild beasts. They speak no language, but bark like dogs, and in this manner make themselves understood by each other…All, both men and women, have tails above their hips, like dogs, but longer and more hairy…They are just, and live longer than any other men, 170, sometimes 200 years.”

There is of course the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, who writes in the chapter on Ethiopia in his famous work The Natural History:

According to Woods, the Eastern Christian (or Greek) tradition came to interpret the account of his being ‘dog-headed’ literally, which is why Byzantine icons often depicted St. Christopher with a dog’s head.

“In time, of course, this led to a reaction against St. Christopher. The Latin tradition developed along different lines, however, since early Latin translations did not always render a literal translation of the original Greek term “dog-headed” (kunokephalos), and some seem to have translated it as “dog-like” (canineus). This was amended to read “Canaanite” (Cananeus) as time progressed since it was obvious that he could not really have been “dog-like”, as per Woods.

The ‘reaction’ that Woods speaks about, came in 1722 when the Russian Orthodox Church’s Holy Synod formally prohibited depicting Saint Christopher with a dog’s head, which had been the case since the fifth century onwards in the Eastern Orthodox world.

However, the portal Greek Reporter notes that ‘Old Believers’ or Russian Orthodox Christians who rejected 17th-century liturgical reforms, “continued creating and venerating dog-headed Christopher icons well into modern times”.

According to Woods, “It is important at this point to emphasize that the description of Christopher as from the land of the dog-headed has absolutely nothing to do with the Egyptian cult of the jackal-headed god Anubis. The real explanation is rather more prosaic”.

He says that the civilised inhabitants of the Greco-Roman world had long been accustomed to describing those who lived on the edge of their world and beyond as the strange inhabitants of stranger lands, cannibals, dog-headed peoples and worse.

The representation of Christopher with a dog-head merely signified that he came from the edge or periphery of the Greco-Roman or ‘civilised world’. The Marmaritae did indeed inhabit such a peripheral region.

However, the metaphor was taken quite literally in the Eastern tradition and hence the resultant iconography.