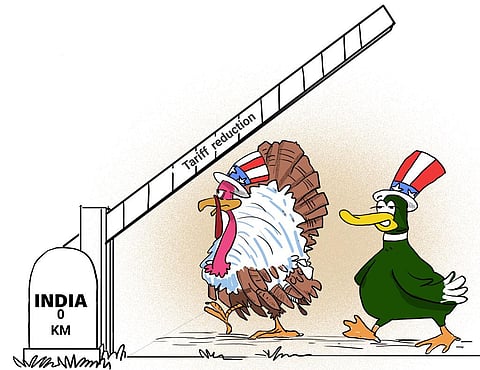

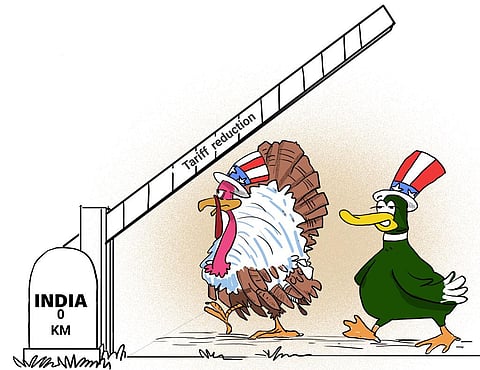

After a protracted 17-year dispute at the World Trade Organization (WTO), India has agreed to reduce tariffs on frozen turkey and duck imports from the US from 30 per cent to just 5 per cent. The agreement, announced during the G20 summit, also includes tariff reductions on a range of other products, including chickpeas, lentils, almonds, walnuts, apples as well as fresh, frozen, processed and dried blueberries and cranberries, boric acid and diagnostic reagents.

The Indian poultry industry is concerned that the agreement will allow the US to dump cheap meat in the country, which would adversely impact the domestic market. While the agreement currently does not include chicken, the industry fears that it might be brought within the ambit in later negotiations between the two countries. A source close to the negotiations tells Down To Earth (DTE) that the US officials wanted chicken on the list of products with reduced import tariffs, but dropped it due to a lack of consensus between the two countries.

The trade dispute dates back to 2007, when India imposed a ban on poultry imports from the US, particularly chicken, due to concerns over avian influenza (bird flu). The US challenged the ban at WTO and won the case in 2014. India reluctantly opened up its markets to US poultry imports in 2017, along with high import duties to protect domestic players. The deal, announced on September 8, shows that India is succumbing to US demand.

Accounting for 10 per cent of India’s poultry population, ducks “occupy an important position next to chicken farming in India”, as per the Central Avian Research Institute in Itanagar, Uttar Pradesh. Duck rearing is mostly concentrated in the eastern and southern states of the country, mainly coastal regions, and is responsible for about 7 per cent of total eggs produced in the country.

Duck breeders tell DTE that the market is limited compared to chicken, and the reduced duty will adversely affect them. This could have a widespread effect, as duck rearing is a common practice among rural communities, especially in the tribal belts of the coastal states.

It can also impact the chicken market. “If duck and turkey meat are available at throwaway prices, consumers might migrate will eat into the chicken market. Around 80 per cent consumers are sensitive to price and can evolve their taste habits,” says F M Sheikh, national president of industry body Poultry Farmers Broilers Welfare Federation in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh.

Sheikh’s fear is not unfounded. The US mostly consumes fillets, made from breast meat of birds, and ships the remaining bird parts to developing countries. “In the US, the fillet is indirectly subsidising the production of the rest of the bird, and, as a result, all other parts except the bird can be sold at a price far below the production cost. It is also more cost effective for US producers to dump their chicken parts abroad than to pay for disposal within the country,” says K V Biju, national coordinator of farmer group Rashtriya Kisan Mahasangh.

Chicken from the US currently attracts an import duty of 100 per cent. Still, importing chicken leg from the US is cheaper than the cost of producing it in India. The cost of production for chicken legs is estimated at around US $700-$800 per tonne in the US. “With 100 per cent duty, it is available at $1,500-$1,600 per tonne, while the cost of production of processed chicken in India is around $1,800 per tonne,” says Biju. The US is the world’s largest producer of poultry meat and its second-largest exporter.

“There is already the issue of overproduction of broiler chicken in India, as a handful of big companies have entered into contracts with farmers to keep prices low. If the US starts dumping their products, it will be a death knell for small farmers,” says Sanjay Sharma, who runs a broiler brooding farm and is a managing committee member of industry body Poultry Federation of India in Kanpur.

The move is expected to have a ripple effect, impacting many more allied sectors. Feed accounts for about 70 per cent of production costs and US poultry production has a competitive advantage in the world due to abundant domestic feed resources, primarily soybean and corn farming. Another concern, which is not highlighted enough, is the introduc-tion of genetically modified poultry and its associated feed, which are not allowed in India, but remains common in the US.

The decision to liberalise imports from the US is ironic when backyard poultry farming—which is likely to be worst hit by the move—is one of the strategies under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s plan to double farmers income.

In fact, the ban in 2007 led to a sudden boost in poultry farms in the country, from just 0.5 million then to 52 million in 2012, as per the livestock census. Poultry is one of the fastest-growing segments of the agricultural sector in India today. While the production of crops has been rising at a rate of 1.5 to 2 per cent per year, that of eggs and broilers has been rising at 8-10 per cent per year. “India was one of the major countries that led an alliance of developing countries to fight US subsidies. If India allows easy import of subsidised US agricultural products, it is not only giving up on its long-held stand at WTO, but also letting down other developing countries that fought with India on US subsidies,” says Biju.

This was first published in the 1-15 December, 2023 print edition of Down To Earth