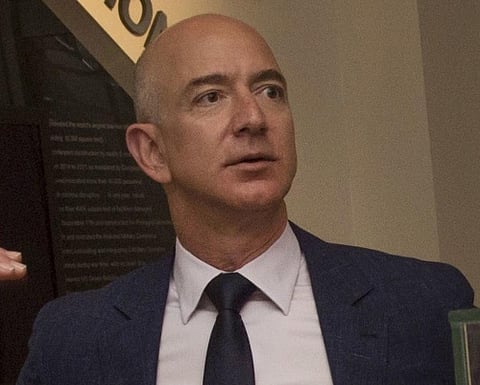

Getting Amazon to pay its taxes could be Jeff Bezos’ biggest climate action

Union commerce and industry minister Piyush Goyal in January 2020 issued a thinly veiled threat to the Washington Post for its recent coverage of the current Indian regime. He pointed out that Amazon Inc, owned by Jeff Bezos like the Washington Post, was having a negative impact on India and did not align with the government’s economic vision.

It is a testament to the power of an American passport (and $130 billion) that this is how far the government could go, in a country ranked 140 in the World Press Freedom Index.

But the liberal criticism Goyal drew did not relate to press freedom. It, instead, ridiculed his attack on Amazon. However, the US financial press led by the Wall Street Journal grudgingly stopped just short of praising India for following a China-inspired strategy to protect domestic infant enterprise.

On February 17, 2020, Jeff Bezos announced that he was giving $10 billion (about 8 per cent of his personal wealth) to a new Bezos Earth Fund tasked with combating climate change. His Instagram statement did not immediately make clear what the money would be spent on.

For now, a look at the past climate record of Bezos and Amazon is merited.

There is much speculation that the announcement is merely an effort to greenwash the recent gagging of Amazon Employees for Climate Justice, which highlighted the company’s close links with the fossil-fuel industry. But online shopping’s impact on the environment is complex: Some of the older analysis suggest it is better than a trip to the local mom-and-pop; but with Amazon Prime and Amazon Prime Now (offering two-hour delivery) now delivering objects as cheap as shaving razors, the climate math has likely shifted in favour of brick and mortar.

More worryingly, the role of Amazon’s delivery vehicles in causing congestion-induced pollution in world cities such as New York, London and Singapore has been well-documented.

But there is a more fundamental issue at stake here. The so-called Amazon Effect rests critically on enhancing consumerist urges, not just through low prices and convenience but also by the very philosophy of instant “fulfillment” of a consumer’s every desire. Besides raising demand for carbon-intensive goods that no one needs, Amazon’s cheap prices are uprooting the repair-and-use economic model of the poor world and replacing it with a use-and-throw model. Sky-rocketing consumption is overwhelming any gains in carbon efficiency.

But Amazon’s problematic approach to climate change goes beyond the planetary harm inherent to its very business model. In formulating its decarbonisation plans, Amazon’s engineers appear not to have understood climate science, nor have its famed lawyers understood global climate agreements.

In September 2019, Amazon co-founded The Climate Pledge, which aimed to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement 10 years early, on the basis that it implied attaining net-zero carbon emissions by 2040.

The Paris Agreement sets no such goal — it merely adopted a target of limiting the global mean temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius and commissioned the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to investigate a 1.5°C target.

Despite being unexceptionable in its science, the IPCC’s special report on Global Warming of 1.5°C (2018) was not adopted by CoP 24 [the 24th conference of parties to the United Nations Framework convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)] at Katowice due to the objections by the United States, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Neverthless, what was the IPCC’s message to countries and companies committed to climate action?

The panel estimated that the world as a whole needed to attain net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 (and net-negative emissions thereafter) for a 66 per cent chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C. In keeping with the IPCC’s remit, the report does not recommend a target for individual countries, or indeed for companies which have become the focus of this year’s British CoP presidency.

Such targets are the subject of climate negotiations, to be driven by the principles of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (simply, “equity”) enshrined in all climate agreements, including the UNFCCC agreed to at Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and the 2015 Paris Agreement.

While accounting for historical responsibility as well as present-day ability is necessarily subjective, most analyses indicate that to stay safely within 1.5°C of warming, developed countries and their corporations need to attain net-zero by 2030. As Greta Thunberg tweeted on Tuesday, any mitigation target must not only take equity into account but also deliver massive cuts within the next decade.

There is a growing discourse around “science-based targets”, particularly when it comes to climate action. But the much-touted net-zero laws passed by developed countries such as the United Kingdom, France and New Zealand have all set what may be called an ignorance-based target of 2050.

It may be mentioned that at least one fossil-fuel guzzler from a developing country — Indian Railways — has set a 2030 deadline to attain net zero, going well beyond any science-based target. The 2030 target of the world’s second largest person-and-material transport operation puts the 2040 target of Amazon, a company that still sells itself as an internet startup to shame.

Bezos’ past activities beyond Amazon also give no cause for comfort. The dilettante billionaire spends $1 billion a year on Blue Origin, a private space-travel venture.

It is based on Bezos’ insight that while the human brain requires 60 watts of power, the developed country “civilisational metabolic rate” was closer to 11,000 watts. For savages to attain this civilisational metabolic rate and produce Einsteins and Mozarts would require more resources than the earth could support, especially through climate-friendly options. This necessitates the exploitation of outer space.

Apart from the racism implicit in this line of thought, Gandhi’s famous quote comes to mind for the millionth time: “While the earth may have enough for every person’s needs, it simply could not cater to every person’s greed”.

The Ford and Rockefeller Foundations once pushed in-optimal input-intensive solutions on Indian agriculture to make for a chain of events that could neither be described as green nor as a (production or yield) revolution, except maybe for the fertilizer industry. As Norman Borlaug wrote to a Rockefeller group fertilizer company, poor-world farmers would soon be “begging for fertilizers”.

Besides pushing in-optimal policy choices to serve vested interests, the sort of money that corporate philanthropies such as the Gates Foundation bring in can completely overwhelm democratic policy choice in poorer countries.

Any heroic attempt by Bezos to save the planet must begin with fair pay and working conditions for those who labour in Amazon’s warehouses and delivery vans. But their plan is to replace them with robots and drones.

In 2018, Amazon held a nationwide competition where impoverished communities across the US fell over each other to offer tax-breaks and subsidies to tempt the company to set up in their city. In the same year, it paid no income taxes in the US (where multinationals are typically forced to pay more tax than in other jurisdictions) despite a near-doubling of profits to $11.2 billion.

It is, thus, crucial that Amazon also start paying its fair share of taxes globally. For both effective climate action and climate justice demand that any large sums spent be subject to democratic discussion and debate.