2022: Horrible, just horrible. The year that brought the world to its knees.

This was when we started with a sliver of hope. After two years of surreal and back-breaking events when the novel coronavirus had shut down our world, we thought the worst was over.

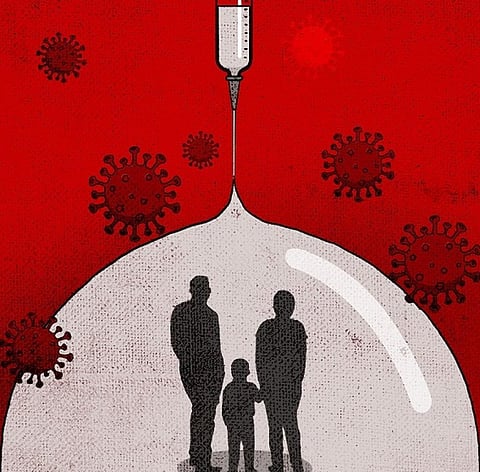

The virus had become less virulent; we were in the phase of co-living with it. More comforting, there were vaccines that offered us protective cover, which could control the high mortality rate. The worst, as I said, was seemingly over. We collectively exhaled. Now, we could rebuild our world.

We hoped that this new phase of reconstruction would be based on the learnings of the past years. We would do things differently, knowing that we need to do more for public health; we would invest in the shattered economies of the poor who were worst hit by the pandemic and lost livelihoods.

Our world would be greener, more inclusive and more humane. We had seen the flights of migrant workers from our cities and countries. It was clear that the cost of production could not be discounted anymore when we factored in the real value of work.

We also understood the huge opportunity to invest in the rural hinterland so that people who had returned would only leave because of the pull of the city, but not the push of their desperate economic situation.

All in all, the horrors and human tragedy had changed us all. We saw the value of humanity and the need for doing more to hold on to this hope. But how quickly all these unraveled.

Transitional offsets

By mid-February, 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine, our world became more divided, more polarised and deadlier. The eventful year, culminating with the climate conference in Egypt (COP27), had two dominant trends.

One, the energy market was in turmoil. Europe learnt that its energy policy had left it dependent on Russia and so deeply vulnerable to this unfolding crisis.

Prices of conventional energy have increased so much that the post-War generation of Europeans and Britons, who never witnessed economic hardship and scarcity, is now experiencing the pain of a cold and dark winter.

The response of the rich has been to turn again to the sources of energy that they have always depended upon — and which, for a brief moment, they had decided to wean off because of the climate change crisis. This year, in spite of all the rhetoric and big talk, the already developed world has gone back to “drill baby drill”.

Let’s be clear that even if Europe sticks to its green commitment — notwithstanding it being re-invested in brown energy — it is bad for climate and worse, it is really bad optics.

How can the emerging world, that is still in the throes of energy poverty, be asked to move to the costly green transition, when at the drop of a hat, the rich go back to fossil fuels, including restarting coal plants and mines.

They can call natural gas green or transitional but the fact is that it is fossil fuel and it needs to be phased out. This part of the world does not have any carbon budget left for the use of fossil fuel, even slightly cleaner natural gas.

Let’s also be clear that the idea that these investments (like the opening of UK’s coalmine in Cumbria) are somehow carbon neutral because they invest in “offsets” — in most cases paying for trees to be planted in the parts of the world that are being told to switch off lights — is hogwash, if not downright immoral.

So, this year’s one big trend has been the reversal of gains when it comes to energy transition. Let’s be clear about this and not pussyfoot around with some cute nothings about how renewables are still growing.

Yes, there is no doubt that the higher cost of energy benefits not just the fossil fuel industry coffers but also makes for a better business case for investment in renewable and clean energy.

But we are far from the energy transition that we desperately need and this year has seen us dial back, not dial forward. This we must remember as we enter a new year. We have to fast forward the change in the coming year.

The second overwhelming trend of 2022 is the impact of climate change. It is now real, in our face and devastating every region of the world. In India, our report Climate India 2022: An Assessment of Extreme Weather Events January-September using government data shows that we have seen one extreme weather event a day in the first nine months.

This number hides the human face, particularly of the poor, who suffer the worst devastations as they have to cope with repeated damages to their sources of livelihoods. We have to remember this as we move forward to 2023.

This year has been the year of revenge of nature; not a single part of the world has been left unsinged. It tells us that things will only get worse as temperatures continue to rise and we tip over to the catastrophic unknowns.

The losses and damages that the developing world is seeing today are attributable to climate change and this, in turn, is because of the stock of greenhouse gas emissions that is in the atmosphere. There is no question about ducking this inconvenient truth.

An order we all want

In the face of these two trends — growing insecurity of the rich and growing vulnerability of the poor — we have seen the worst manifestation of human behaviour. The global community, which till last year, was talking about the need for vaccine cooperation and interdependence, has gone back to shoveling dirt and provocation in others faces. Our leaders want to accentuate the differences, not the common objectives to work together for a secure future.

In 2022, it is confirmed that there are two world orders: the one led by the US and its allies (India is sometimes counted in this), with lofty goals of democracy and free speech; the other, more obviously, authoritarian.

In all these, there is the growing influence of a more aggressive China, which has made gains (in spite of the still raging pandemic and the economic slowdown) on the global stage.

Besides, the war for dominance over energy is at full throttle — each block is working to carve out their followers and suppliers of fossil fuels and rare minerals for next-gen production. The race is on and at this moment, China with its eye on materials and technologies seems to be winning. So, not just Ukraine-Russia, the world is now at war.

There is also talk of the need for protection of national economies — reversing the free trade bonhomie of the 2000s. But this localisation or de-globalisation is tough in the face of increased cost of production due to higher costs of labour or meeting environmental standards. The world turned itself into a giant consumer of goods when it signed the free trade agreements and now it seems there is no turning back.

But we must. This is the call for 2023. There is even more to be done, than yesterday. Each year that we lose in procrastination is another black mark against our generation.

There is no question that climate change impacts will get worse. There is also no question that we need to act at scale and speed to transform economies so that they are future ready. This is where we must focus.

This is not a time for war; this is not the age for divisions — even those based on our values and views of the world.

We need to have a common minimum programme that brings all countries together on the only issues that matter for humanity: how to avert the existential crisis we face and to build a just and inclusive world order.

This is only possible when we go back to a rule-based system of global governance — one that sets rules for the rich and powerful and not just for the poor to abide by.

In the case of climate change this means that we must ensure that there are global standards of responsibility that are based on the contribution of gases that all must follow — this will set a level playing field so that old polluters and new polluters are all required to do what is then agreed upon.

Then we need to reorder the financial systems so that there is money available to do development differently.

The fact is that the deck is stacked against the emerging world when it comes to investment in cleaner energy sources. There is no money; the cost of finance is high; and high debt burdens mean that many countries pay more than what they even receive in the name of climate gratuity.

This cannot go on. But as yet, we are seeing little movement of the needed change of the global financial architecture — not surprisingly as the reformers, the powerful countries and their banks, are the ones who need to be reformed.

The New Year can and must be different. There is no turning away from the urgency of the change that is needed.

What will make the difference, I believe, is our ability to speak truth to power — for too long we in civil society have tried to mollycoddle and massage the message to make it more palatable.

It is our helplessness that we have accepted all the bad global deals that have been shoved out as the only pragmatic and possible options in the circumstances.

This must change. We need to start calling it as it happens. Not because we want to name and shame, but because we deserve better.

The second is about our ability to listen to each other. It is not that the world is divided; we are divided in our minds and thoughts. We do not even know that “another” exists. The media censorship is complete. If you are not with us, you are not in our circle of words.

Dissent and dialogue are what we must celebrate in 2023. We will then build that new world that we all so desperately hope is still possible.

Read more:

- Special Relationship: New Anglo-American energy partnership is Western fossil fuel hypocrisy at its best

- Climate hypocrisy? Germany’s coal-fuelled power sector more polluting than India, China currently

- EU’s Carbon Border Tax: Is it regressive and protectionist or an incentive for global decarbonisation?

- 2022 too short, too far: How the Russian invasion of Ukraine impacted the world

This will be published in the forthcoming State of the Environment 2023 brought out annually by Down To Earth-Centre for Science and Environment. To book advance copies, click here