The concentration of ozone-depleting substances in the atmosphere has reduced to reach a significant milestone this year.

The announcement was made August 24, 2022 by the scientists of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), an American scientific and regulatory agency within the United States Department of Commerce. NOAA forecasts weather and monitors oceanic and atmospheric conditions.

Ozone is a highly reactive molecule formed of three oxygen atoms found primarily in two regions of the atmosphere. About 90 per cent of Earth’s ozone resides in the stratosphere above the troposphere — the layer closest to Earth’s surface.

The region of the stratosphere with the highest amount of ozone is called the ozone layer. The stratospheric ozone layer absorbs the sun’s ultraviolet rays and protects all biological systems on Earth from these harmful rays.

NOAA’s Ozone Depleting Gas Index tracks the overall stratospheric concentration of ozone-depleting chlorine and bromine from long-lived ozone-depleting substances (ODS) relative to its peak concentration in the early 1990s.

Air samples collected at remote sites around the globe were analysed by NOAA scientists in an annual exercise. They found the overall concentration of ODSs in the mid-latitude stratosphere had fallen just over 50 per cent.

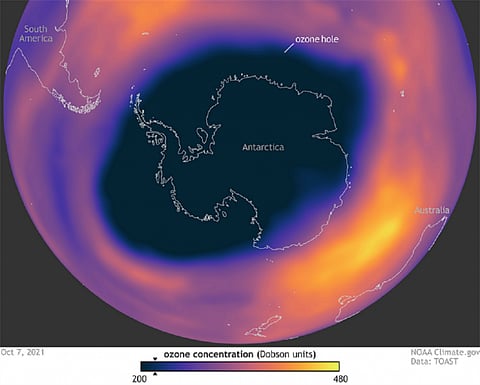

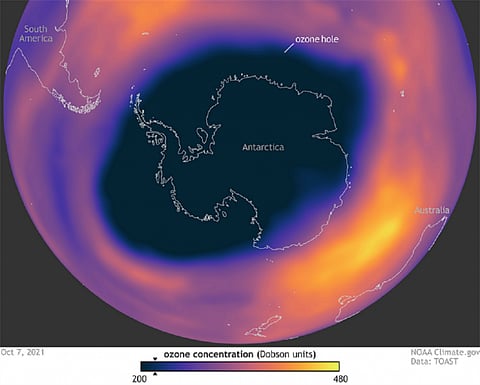

This means the ODS levels in 2022 are back to those observed in 1980 before ozone depletion was significant. However, the pace of reduction in ODSs over Antarctica, which experiences a large ozone hole in spring, has been slower.

This slow but steady progress over the past three decades was achieved by international compliance with controls on production and trade of ODS in the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer — an international agreement made in 1987.

The 2022 index for the Antarctic has fallen 26 per cent from peak values in the 1990s, with recovery of the Antarctic ozone layer projected to occur sometime around 2070.

“It’s great to see this progress,” said Stephen Montzka, senior scientist for NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory. “At the same time, it’s a bit humbling to realise that science is still a long way from being able to claim that the issue of ozone depletion is behind us.”

In the 1980s, the scientific community discovered that a class of human-made chemicals was seriously damaging this protective ozone layer, creating a giant “hole” in the ozone layer over Antarctica and smaller but still worrisome depletion in mid-latitudes.

As part of the US response, Congress mandated that the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and NOAA monitor stratospheric ozone and ODSs in the 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act.

Scientists at NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory created an index. The Ozone Depleting Gas Index renders the results of a series of complex analyses into a single number that tracks the total abundance of these chemicals and how the threat they pose to the ozone layer is changing over time.

The year 1980 was selected as the benchmark year for the index because scientific and policy communities have long viewed it as the date when ozone depletion first became obvious.