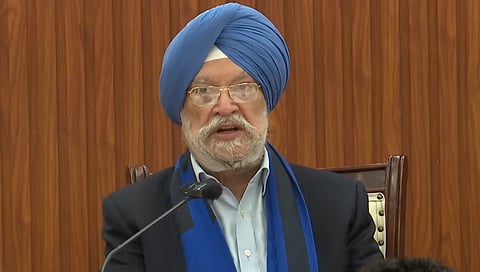

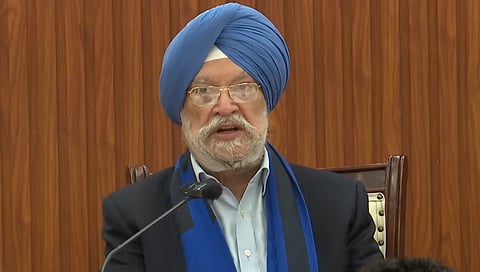

India can no longer treat geopolitical shocks in oil markets as temporary disruptions, Union petroleum and natural gas minister Hardeep Singh Puri said, warning that price volatility driven by conflicts, sanctions and trade measures has become a structural feature of the global energy system.

Speaking with reporters at the India Energy Week 2026 curtain raiser conference, Puri said despite adequate global supply, crude prices remain vulnerable to political flashpoints in West Asia, disruptions to shipping routes and unilateral policy actions by major economies, particularly the United States.

For a country that imports over 85 per cent of its crude oil, such instability poses sustained risks to macroeconomic stability, inflation management and fiscal planning. “Geopolitics today has a disproportionate influence on energy markets,” Puri said, noting that even minor developments can trigger outsized price reactions.

He added that traditional assumptions of market correction through supply-demand balance no longer hold in a world shaped by sanctions, export controls and trade restrictions.

India, he said, has responded by diversifying its crude import basket, expanding strategic petroleum reserves and improving refining flexibility. However, these measures alone are insufficient to insulate the economy from repeated global shocks.

Puri emphasised that energy security must now be understood more broadly—extending beyond oil and gas to include access to critical minerals that will underpin the clean energy transition. As global competition intensifies for resources such as lithium, cobalt and nickel, India faces risks similar to those it has long encountered in crude oil markets.

In this context, he highlighted the government’s renewed focus on Samudramanthan, India’s deep-sea exploration mission, as a strategic response to future resource vulnerabilities. The initiative aims to tap polymetallic nodules from the ocean floor, which are rich in minerals essential for batteries, electric vehicles and renewable energy technologies.

“Energy security in the future will depend as much on minerals as it does on hydrocarbons today,” Puri said, arguing that countries failing to secure upstream access could find themselves exposed to new forms of geopolitical pressure.

India holds exploration rights in the Central Indian Ocean Basin under a contract with the International Seabed Authority, positioning it among a small group of countries with deep-sea mining ambitions. According to the minister, building domestic technological capability in seabed exploration and extraction is critical to reducing long-term dependence on external supply chains.

At the same time, Puri acknowledged concerns around the environmental impact of deep-sea mining, noting that ecological risks must be carefully evaluated. He said India would pursue the programme within international legal frameworks and scientific safeguards, emphasising that resource security cannot come at the cost of irreversible environmental damage.

The minister also linked India’s resource strategy to broader global realignments, where energy and trade are increasingly being used as geopolitical tools. He cautioned that importing nations must adapt to a world where energy markets are shaped less by economics and more by strategic contestation.

As oil markets remain volatile and the clean energy transition accelerates, Puri said India’s challenge lies in navigating immediate import dependence while investing in long-term autonomy—both above and below the sea.