Madhya Pradesh’s capital Bhopal lies just 250 kilometres from the industrial hub of Pithampur in Dhar district. It took four decades for the hazardous and toxic waste from the 1984 disaster at the defunct Union Carbide factory to reach the incineration facility, thanks to legal tangles and administrative apathy.

The toxic waste, stored at the factory site in Bhopal’s Chola area since the disaster, was transported to Pithampur on January 1, 2025. Under the supervision of the Bhopal Gas Relief and Rehabilitation Department, the 337 metric tonnes of waste was securely packed into 12 large containers and transported via a specially created green corridor through Sehore, Dewas, and Indore districts.

The final destination was Tarapura village, where Pithampur Waste Management Pvt Ltd, in collaboration with Re Sustainability Ltd (formerly Ramky Enviro Engineers), is to incinerate the waste.

The move follows a directive from the Supreme Court issued in 2014 and a recent ultimatum by the Madhya Pradesh High Court, which ordered the state government to act within four weeks.

Ironically, Pithampur, touted as the ‘Detroit of India,’ was developed in the early 1980s under the former Chief Minister Arjun Singh. The same Singh faced widespread criticism in 1984 for facilitating the safe passage of Warren Anderson, the then head of Union Carbide India Ltd (UCIL) and a United States citizen, out of Bhopal in the aftermath of the catastrophic industrial disaster.

As the 12 secured truck containers rolled out of the abandoned factory late on New Year’s Day, hundreds of residents living near the ghost factory in Bhopal expressed relief.

The late Alok Pratap Singh, the original petitioner who fought for decades to remove the chemical waste, would have likely been the happiest. He passed away a few years ago, never seeing the waste he battled to relocate finally leave the city.

The UCIL plant had been producing pesticides until it was shut down in December 1984, following the catastrophic gas leak on the night of December 2-3, 1984. The deadly release of methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas killed thousands instantly and led to the deaths of many more in the years that followed.

Since 1984, numerous legal cases have been filed in Indian and American courts, ranging from compensation claims for the deceased to the disposal of the toxic waste. Scientific reports, including those from pollution control boards, confirmed the waste’s role in water contamination, necessitating incineration in a foolproof process elsewhere.

The first petition for waste removal was filed in the Madhya Pradesh High Court in August 2004, two decades after the disaster. Yet the sluggish legal process and administrative delays extended the timeline to 40 years.

The High Court finally took a firm stance in December 2024, directing the state government to shift the waste within four weeks. This marked the beginning of the historic relocation process.

“Living next to the toxic waste gave us sleepless nights,” said Abid Noor Khan, a resident of the area who lost two relatives in the 1984 disaster.

Over the years, various locations, including Ankleshwar in Gujarat, were identified for incinerating the waste. However, in 2007, the Gujarat government, led by then-state Chief Minister Narendra Modi, refused to allow it near Bharuch. Attention then shifted back to Pithampur, where earlier protests had delayed progress.

In 2015, the Supreme Court ordered a trial incineration of 10 metric tonnes of waste from UCIL at Pithampur, which proceeded without any reported environmental damage. Official sources told Down To Earth that the remains of a Cochin pesticide factory were also burned at the Pithampur factory prior to 2015. Both were deemed fine by the Supreme Court.

The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has outlined a detailed process for the incineration of the 337 metric tonnes waste, starting with an initial 90-kilogramme feed. This will test the furnace’s capacity to handle the toxic material at temperatures of up to 1,200 degrees Celsius. If successful, the remaining waste will be processed gradually.

The hazardous waste is not in liquid form, but rather solid and largely covered in sand and soil, with no plastics present, according to a high-ranking official involved in the process. The waste was packed in large PVC bags and stored for decades in Bhopal without reported injuries or illnesses.

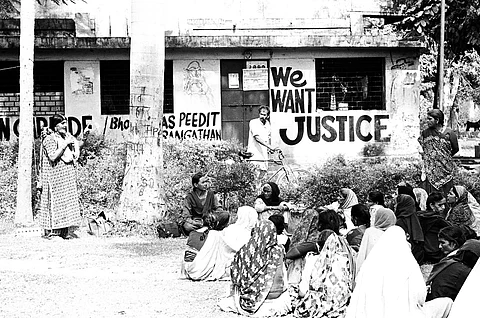

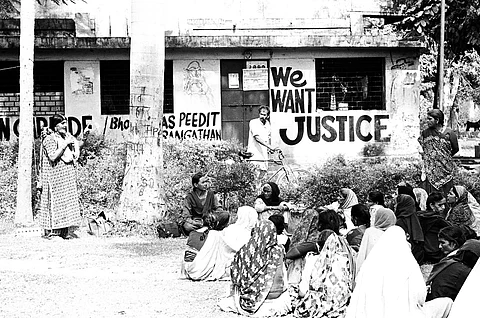

Despite this progress, opposition persists.Protests by local citizen groups and Congress party workers in Pithampur has escalated to become a law and order problem. Two youths tried to self-immolate near the site on Friday morning while protesting the incineration in Pithampur.

A group of doctors also recently petitioned the Indore Bench of the Madhya Pradesh High Court to halt the waste transfer to Pithampur, just 30 kilometres from Indore city. The plea is likely to be heard january 6, 2025.

Meanwhile, gas disaster-related non-governmental organisations have criticised the Bharatiya Janata Party-led state government for failing to clean the entire 85-acre UCIL site, which still harbours underground toxic waste. Wild vegetation now covers much of the disused premises, where entry remains restricted.

With the first 10 kilograms of waste set to be incinerated under tight security and CPCB supervision, the government is hopeful that the process will proceed without incident. “A dark chapter associated with the Bhopal Gas Tragedy has been closed,” remarked a visibly relieved Swatantra Kumar, Director of the Gas Relief Department.

The State Pollution Control Board and CPCB had been monitoring the process, and it had been ensured that the fumes from the furnace did not mix with the fresh air surrounding the small Tarapura village, causing new problems for the locals.

If all goes according to plan, the total 337 metric tonnes of hazardous waste will be incinerated within four to five months, bringing Bhopal closer to healing from its toxic legacy.