Kalboishakhi’s uncertain fate: Remembering the age-old harbinger of monsoon in an era of weather vagaries

Kalboishakhi (কালবৈশাখী), a word rarely heard colloquially in Kolkata nowadays, used to be as frequent a part of our conversations and childhoods. Originating from the words 'kal' and 'boishakh', it literally means 'a fateful thing' which occurs in the Bengali calendar month of Boishakh (April-May).

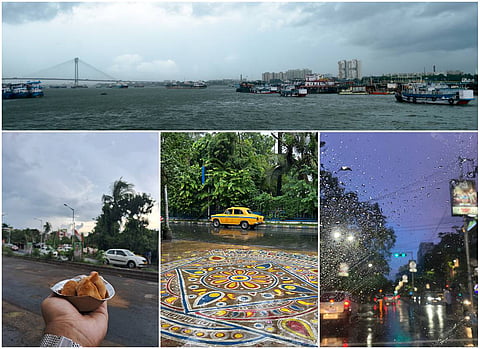

These vigorous nor'westers are harbingers of monsoon, and often have devastating impacts on agriculture and human life but are still hailed as godsent for providing respite from the hot and humid summers of Bengal.

The same storms now seem infrequent and unpredictable; almost staggeringly absent from reality.

For many Bengalis, the word itself would evoke a strong reminder of rainy evenings in Kolkata.

For me, it's reminiscent of the aftertaste of gorom shingara (hot samosas) and beguni (brinjal fritters) lingering in my mouth, accompanied by Maa’s announcement,"Jhor ashche!" (a storm is coming!).

These memories keep flitting between the conscious and unconscious recollections of what I remember growing up. Till the time I was 10, I remember an imitation of excitement when the skies would start to darken, signalling its arrival.

Yet, in the last several years I do not recall the word being used in my household with the same familiarity that it once was. The phenomenon, along with its name, seems to be falling into redundancy.

But that wasn’t the case in the collective childhood of my Gen Z generation that has grown up to witness changing times at a pace that is remarkable from a sociological perspective.

These were the times when Instagram was yet to invade our lives but we lived through memorable experiences without knowing that they could be shared as instagrammable reels and photos in today’s times.

Climate change tramples cultural nuances

It’s said that a language dies every 14 days, with 20 per cent of the world’s 7,000 languages facing the constant threat of becoming extinct.

It is dystopian to imagine how climate change is further exacerbating the extinction of languages since communities are forced to migrate and adapt, resulting in the disruption of intergenerational transmission of words like the good old Kalboisakhi.

The Pacific and South and East Asia; one of the most linguistically diverse regions are also the most vulnerable to climate change.

American linguist WY Leonard says that even in communities who might not be facing a threat of ‘language loss’, there is ‘still a loss for words’ to describe the uncertainty in their natural environments.

What a stark reminder of the uncertain fate of the fateful kalboisakhi…

Rather than serving as physical reminders of days bygone, words like these closely resemble 'sites of remembrance' - which are not physical locations, but rather, places or events that serve as a symbolic element of nostalgia or a community's memorial heritage.

For many Bengalis, kalboishakhi is precisely a paragon of the above written — a shared experience that has shaped the region's environmental and cultural identity for generations. The words we use (or lose) are themselves artifacts of our historical relationship with the environment.

As climate change tramples on certain words from our diction, it is also erasing parts of our cultural history and ecological knowledge. If the pattern of these storms changes significantly, the word kalboishakhi might also lose its meaning and quietly exit our lives to being remembered as a relic of the past.

Source of literary inspiration

These nor’westers have served as a recurring motif in Bengali literature for years.

The kalboishakhi of today, potentially altered by global warming, may not be the same phenomenon that inspired the poets of yesterday.

Most famously in Rabindranath Tagore's works, he invokes the storm in his famous poem ‘Borshosesh’, literally meaning ‘the end of the bengali calendar year’ when kalboishakhi manifests itself.

It is well documented that the monsoon was Tagore’s favourite season.

Geetobitan, one of his seminal works, was famously divided into the six seasons of the Bengali calendar - Grishma (summer), Borsha (monsoon), Sharat (autumn), Hemanta (late autumn), Sheet (winter), and Basanta (spring) - each having been written after deriving from the natural world, had the most poems inspired from Borshakal.

Adapted from Tagore’s novella Nastanirh, Satyajit Ray directed Charulata, which he regarded as his personal favourite creation.

In the film, the protagonist Amal, enters Charu’s life ‘like a hurricane’, unforeseen and intemperate, accompanied by the relentless screeching and swirling of clouds in the background.

If that wasn’t enough, in Jibanananda Das's poetry, the interplay of seasons and human emotions reaches its zenith in his famous poem ‘Banalata Sen’.

Mohit Lal Majumdar’s poem literally named ‘Kalboishakhi’, describes the astounding ferocity of the storm while Anupam Roy’s recent eponymous song, uses the storm to refer to the fierce emotional conundrum of the human condition.

Needless to say, metaphorically or literally, these storms have been a congenital inspiration for artists in Bengal since time immemorial.

In everyday Bengali language, even weather-related idioms and proverbs abound: expressions like ‘jole-bishorjone jaoa’ (to be washed away in water, meaning, to fail utterly) or ‘jhorer pakhay ura’ (to fly on storm winds, meaning to spread rapidly) are used in passing and demonstrates how weather phenomena are deeply embedded into the Bengali lexicon. While we may be able to translate our words, in clinical, technocratic terms - the meaning between the words is lost forever.

Amitav Ghosh, the champion of climate change-infused literature, talks about the lacunae of environmental concerns which mirrors in his fiction.

He argues that climate change is conspicuously absent from modern fiction, and by extension, from our broader cultural narrative of history: "But is the environmental debate really taking place outside of history?"

Dual losses of language & literature

Climatic issues, despite their monumental importance, have been relegated to the realms of non-fiction and rarely find their way into mainstream literary works. This absence is not merely an oversight but a symptom of a larger cultural inability to fully comprehend and engage with the scale of the environmental crisis.

Our linguistic erosion parallels the literary void that Ghosh identified. Just as modern novels struggle to incorporate the realities of climate change; our languages, especially those deeply rooted in regional ecosystems, are losing their capacity to articulate the subtleties of a rapidly changing environment.

This dual loss, in literature and in language, presents a profound challenge to us: it challenges us to ask ourselves of the opportunities and opportunity costs of the environmental crises we’re facing today.

As we lose the words to describe the world we inhabit, we also lose the history that they bore on their backs; the environmental frameworks that they represent. This is perhaps reflective of our larger tendency to view environmental issues as separate from human history and culture.

By relegating these issues to fact finding missions, are we perhaps perpetuating the notion that environmental issues are somehow external to the fundamental human experience, rather than intricately woven into the fabric of our personal lives?

Recently, in casual conversation with Maa, she lightheartedly teased how I must have forgotten Bangla, how my tongue must have grown more accustomed to the harsh rhythms of navigating life in Dilli.

At the time, I had simply reassured her, a little perplexed by what she had said. Only later did I realise the root of my confusion; the word ‘Bangla’ can mean both ‘land’ and ‘language’; always entwined, forever fated for one to be mistaken for the other.

Or perhaps the universe has a poetic way of making us see what we need to see; for what could be more intimately connected than the language which was named from the very soil from which it sprung?