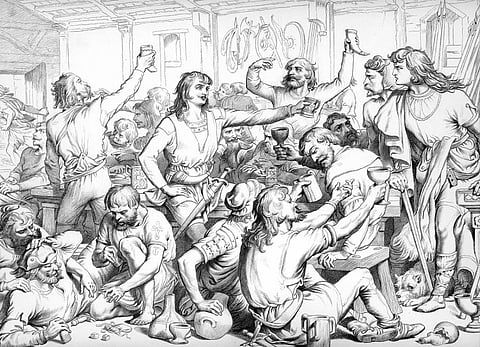

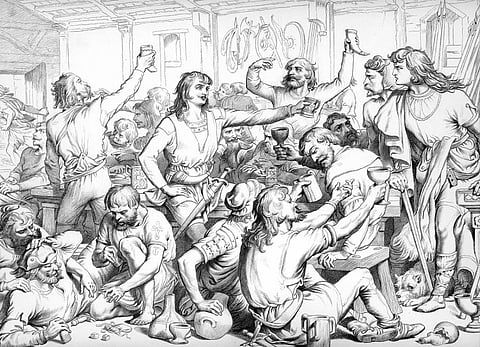

The kings and nobles of Anglo-Saxon England were not the meat eaters they are popularly assumed to be. Rather, they mostly ate cereals. But sometimes, they attended lavish banquets thrown by peasants, who hosted them on their own freewill and not under duress, according to two new studies.

The studies, that have been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication, have been authored by Sam Leggett and Tom Lambert, both researchers at Cambridge University in the United Kingdom.

The researchers studied the period between the fifth and eighth centuries Common Era. This is early Anglo-Saxon England.

Leggett and Lambert note in Food and Power in Early Medieval England: Rethinking Feorm, one of the papers, that Anglo-Saxon kings, especially from the fifth to eighth centuries, have long been assumed to have forced peasants to supply them food all year around. They write:

From the earliest times, kings are thought to have received renders of food, known in Old English as feorm, from the free peasants of their kingdoms.

They add that in its primitive form, (feorm) consisted of a quantity of provisions sufficient to maintain a king and his retinue for 24 hours, due once a year from a particular group of villages.

Both researchers then use two methods to dispute this assumption: Isotopic analysis of bones from this period and quantitative analysis of foods mentioned in the medieval documents regarding feorm.

The foods and beverages that one consumes are incorporated into his / her bodily tissues and thus a chemical signature of diet for the period that tissue was formed is preserved.

Bones preserve a much longer isotopic average of the food consumed for an individual, the researchers write, especially femurs and ribs. Leggett did isotopic analysis on the bones of 2,023 individuals who died between the fifth and eleventh centuries.

Food and Power in Early Medieval England: a lack of (isotopic) enrichment, the second paper notes:

The isotopic evidence, as it stands, gives a picture of fifth-to-eighth-century diets which are more homogeneous than has commonly been supposed, where what people ate was more dictated by regional trends (environmental differences as well as regionally different foodways) and seasonality than purely by social status.

Second, the researchers also went through at least 10 lists from the period regarding feorm. These make it clear that there was a large amount of animal meats and bread loaves in their contents.

The main list cited by the two studies is clause 70.1:20 of the Laws of King Ine, ruler of Wessex, the largest Anglo-Saxon Kingdom.

It states:

From 10 hides as fostre: Ten fata of honey, 300 loaves, 12 ambra of Welsh ale, 30 of clear ale, two full-grown cattle or 10 wethers, 10 geese, 20 hens, 10 cheeses, an amber full of butter, five salmon, 20 pundwæge of fodder and 100 eels.

‘Hide’ was a unit of land measurement at this time from which a certain amount of food was to be obtained. ‘Fostre’ means ‘Sustenance’. The researchers calculated that this clause meant that each meal provided according to its terms would involve 4,140 kilocalories.

“This is a lot of food, far too much for the idea that this represents an ordinary meal to be credible. It is, however, a believable amount to lay on for a feast on a special occasion, with the expectation that everyone would arrive hungry, eat their fill, and still leave leftovers to spare,” they noted.

They also suggested that this would turn upside down the historical assumption that Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were extremely unequal.

“The early documentary evidence (principally law codes from seventh-century Kent and Wessex and narrative works from eighth-century Northumbria) suggests a ranked society with slaves at the bottom, a free peasant majority and an increasingly entrenched noble class associated with service to the kingdom,” the paper on isotopy says.

The conclusion of the second paper however notes that, “The economically dependent peasants of the Rectitudines — the cottars, geburs, and various slaves — were all entitled to be hosted at feorme provided at their lord’s expense at certain times of year, but it was not imagined that they could reciprocate by extending hospitality to their superior. It was only the geneatas whose largesse the lord was expected to accept.”

They then pose important questions:

…what does this signify? Does this make them his peers in some sense? Is he recognising them as fellow landowners? As people with the economic independence necessary to act generously? As full members of the political community he represents?...

“The point is not that these questions are easily answered but that they need to be asked,” they add.

The Anglo-Saxons were Angle, Saxon and Jute migrants from northern Germany and Denmark, who settled in England in the years after the departure of Roman legions from Britain — 410-450 CE. They formed seven kingdoms — East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, Essex, Sussex, Wessex and Kent.

These seven kingdoms were known as the ‘Heptarchy’. Finally, they were merged together to form the Kingdom of England. In 793 CE, the Viking Age began in Britain and Europe and Vikings from Norway and Denmark raided and settled on the island.

Finally, in 1066 CE, the Normans, formed of a synthesis of Vikings settled in northern France, with local Gallo-Romans and Franks, invaded Anglo-Saxon England and conquered it, bringing the land under the ‘Norman Yoke’.