Micro menace

Plastics are cheap to buy, but expensive to use, says Sarah Dunlop, director, plastics and human health of Australia-based non-profit Minderoo Foundation and emeritus professor at the University of Western Australia. She is not talking about the price we pay at checkout counters—but the invisible, long-term cost to our health. “We have studied three chemicals commonly used in plastics—PDBE (a flame retardant), BPA (used in plastics for strength and clarity) and DEHP (used for flexibility)—across 38 countries, covering a third of the global population. The health cost of just these three substances amounts to $1.5 trillion,” says Dunlop. “That is enough to vaccinate every newborn on the planet for the next 200 years.”

Dunlop is referring to the results of “The Lancet Countdown on Health and Plastics”, released on August 3, ahead of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) on Plastic Pollution 5.2, a global meet of countries, civil society and other stakeholders. The meeting on August 5-14 in Geneva is slated to be the final round of negotiations on a Global Plastics Treaty, which was passed in 2022 through a unanimous resolution by the UN Environment Assembly to develop a legally binding agreement to end plastic pollution based on a comprehensive approach that addresses its entire lifecycle.

The Lancet article aims to highlight the staggering toll of plastic on human health, which remains invisible in most public discussions. “In-dustry externalises these costs while our bodies and the environment absorb the damage,” says Dunlop. What makes it worse is that govern-ments continue to heavily subsidise petrochemicals, the raw material for plastics. In 2024, fossil fuel subsidies in the US reached $43 billion—a figure projected to rise to $78 billion by 2050, according to the Lancet article.

Even the draft text of the Global Plastics Treaty, which was under discussion by the time this edition went to print, has a standalone Article 19 on health with no proposed text due to extremely diverging views by the countries negotiating the treaty. Countries were debating whether to scrap the article and include human health in relevant articles or to postpone decisions under it to future Conferences of the Parties. “That is deeply worrying. If we start weak, it becomes easier to eliminate health from the treaty entirely,” warns Dunlop, who is part of a growing movement of scientists and public health advocates urging that the plastics crisis be reframed —not just as a waste or marine pollution problem, but as a public health concern.

Problematic by design

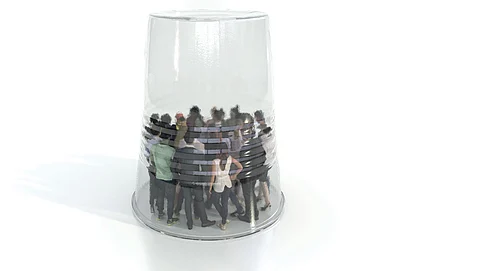

While public concern over plastic pollution is relatively recent, the science linking plastics to health harms dates back to the 1970s. Early studies flagged chemicals like phthalates and bisphenols as endocrine disruptors—compounds that mimic or block natural hormones. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are linked to a range of conditions such as infertility, cancer, cardiovascular disease and neurodevelopmental disorders. Exposure to these chemicals is near-universal. “They are inside our bodies, our children, even babies in the womb,” says Dunlop.

Yet regulation remains woefully inadequate. Of the more than 16,000 chemicals used in plastics, nearly 75 per cent have never been tested for toxicity, says Philip J Landrigan, professor and director of the Global Observatory on Planetary Health at Boston College, US and a co-author of the Lancet article. The 2023 Minderoo–Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health—a multidisciplinary group of experts in planetary health, medical biology, public health and economics—estimates that the global health-related costs of plastic production in 2015 alone reached nearly $600 billion. That is more than the gross domestic product of countries like New Zealand or Finland. The Commission concluded unequivocally that the current patterns of plastic production, use and disposal cause disease, disability and death at every stage of the plastic lifecycle.

Plastic’s toxic footprint begins at production. Manufacturing is energy-intensive and releases over 2 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions annually, worsening climate change and its public health impacts. Communities living near petrochemical plants bear the brunt—they are exposed to harmful emissions that cause respiratory illnesses, cancer, birth defects and neurological damage, says the Lancet report. Children are especially vulnerable, it adds. Exposure to plastic-associated chemicals during pregnancy and early life has been linked to miscarriage, low birthweight, reproductive deformities, delayed lung development, neuro-developmental delays and increased risk of chronic illnesses in adulthood—including diabetes, heart disease and cancer. The risk does not end once the plastics leave the factory. “All plastics leach chemicals that can be incredibly harmful,” says Dunlop. Food packaging, for instance, is a major source of chemical exposure. Consumers are not just ingesting food—they are often consuming plastic-derived chemicals as well.

Then there are microplastics and nanoplastics (MNPs)—tiny fragments formed as plastics disintegrate. These particles are now found in human blood, lungs, liver, kidneys, colon, brain and even meconium, the first stool of newborns. Though the health effects of MNPs are being studied, they could potentially damage cells, cause toxicity from additives and act as carriers for pathogens and pollutants.

With less than 10 per cent of plastic recycled, more than 8 billion tonnes—roughly 80 per cent of all plastic produced—now pollutes the en-vironment, according to the Lancet article. In lower-income countries, where waste infrastructure is often informal and unsafe, this pollution has acute human costs. Informal waste pickers often work in hazardous conditions. Many live near dumpsites that routinely catch fire, releasing toxic fumes. Plastic waste also worsens disease risks. Discarded containers, tyres and bags have become breeding grounds for mosquitoes that transmit dengue and chikungunya.

Another emerging danger is the link between plastics and antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Microplastics act as mobile ecosystems—dubbed the “plastisphere”—where bacteria thrive, share genes and build resistance to antibiotics. According to the Lancet report, this happens in three ways: bacteria form biofilms on plastic surfaces that promote gene exchange; chemical residues like antibiotics and pesticides accumulate, favouring resistant strains and plastic particles transport resistant microbes across ecosystems.

What the world needs

Though plastics currently pose a grave threat to human health, the continued worsening of plastics- associated harms is not inevitable. “The chemicals in plastics should be subject to the same degree of regulatory oversight as pharmaceutical chemicals, since both have a high potential to enter the human body and cause disease,” says Landrigan.

A report released in June 2025 by the University of Birmingham, titled “Plastics, Health and One Planet”, outlines a clear roadmap for the Global Plastics Treaty. It recommends, at a minimum, four critical elements: global bans and phase-outs of the most harmful and avoidable plastic products and chemicals of concern; harmonised standards for safe and circular product design; measures to align financial flows and mobilise resources for an equitable and just transition and mechanisms to adapt treaty measures over time as new evidence emerges.

The report also promotes the One Health approach, which recognises the interdependence between the health of people, animals and eco-systems—all of which must be protected from the harmful impacts of plastic pollution. To support accountability and evidence-based action, the Lancet has also launched a countdown on health and plastics, an independent, indicator-based global monitoring system.

The science is clear, the health consequences are mounting and the tools for change are available. Will countries act with the urgency the crisis demands?

This article was originally published in the August 16-31, 2025 print edition of Down To Earth