'The Olympic Charter contradicts many indigenous physical activities'

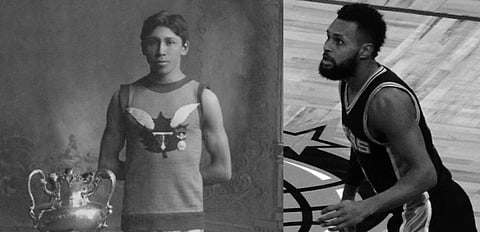

(Left) Tom Longboat, an Iroquois long distance runner who represented Canada at the beginning of the last century. Patty Mills (Right), an NBA star, is Aboriginal Australian. He led the Australian contingent this year at Tokyo. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The 2020 Olympic Games ended in Tokyo, Japan, in early August. Though they played in empty stadiums, athletes nevertheless put up marvellous displays of power, beauty and the spirit of sports. Sports teach us a lot about ourselves. But what role do they play in the lives of the world’s indigenous communities?

Do indigenous people make better sportspersons? Certainly, India’s Olympic squad has always had several members from Adivasi areas, with many bringing laurels for the country. At the global level too, the performance of Cathy Freeman in the 2000 Sydney Olympics is remembered to this day. Yet, why are there exclusive events like the World Indigenous Games?

To get answers to these questions, Down To Earth spoke to Christian Wacker, the president of the ISOH, The international Society of Olympic Historians. Edited excerpts from the interview:

Rajat Ghai: Is there a difference in the outlook of indigenous peoples towards sporting activity and the one presented in the Olympic Charter?

Christian Wacker: On a competitive level, physical activities and sport are part of cultural expression and have always been practiced by humankind. Indigenous people, like all ethnic groups, have their specific traditions regarding physical and sporting activities.

It should not be forgotten that we all belong to some sort of ethnic groups and have our own expressions. Cultural diversity also means diversity in physical performance.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) and later, the Olympic Charter, were created at a time when nation-states began to form around the world and gradually replaced monarchies.

One of the principles that Pierre de Coubertin, the IOC’s founder defined when shaping the framework for the future Olympics was that nations should compete peacefully against each other.

Therefore, athletes should belong to nations and not to cultures, ethnicities or tribes. Also, the competitive element following British sports principles is a key asset at the Olympics.

Both, belonging to a nation and competition, contradict many cultural and indigenous physical activities and by nature are not compatible.

RG: Has Global Sport, including the Olympics, appropriated indigenous sports and culture? Please give examples.

CW: Global sports need globally accepted rules and procedures that do not exclude indigenous people. But ethnic specifications are hardly adopted globally.

Nevertheless, all sports and physical activities derive from specific cultural contexts before they became international.

Surfing is a prominent example. It is culturally related to Hawaii but got globally adopted and therefore, globally practiced. Beach volleyball had been played at Brazilian beaches and today, teams from Scandinavia are among the best in the world.

German gymnastics is also a good example of cultural sports being adopted worldwide. It was originally not even meant to be competitive. But it got tailored to the needs of global practicality and still has outstanding popularity.

RG: How different was the Olympics in 2021 for a Patty Mills from what it was for a Tom Longboat in 1908?

CW: Societies a century ago had been hierarchical and elitist, defining the positions of everybody inside a nation.

Indigenous athletes of the early 20th century participated in the Olympics as representatives of a nation and not as part of a tribe and received credits for that. But not as indigenous people.

Our societies today are diverse and promote themselves as tolerant and having respect for human rights. The situation for indigenous sport stars is different and many of them use their popularity to promote their needs and rights as indigenous people.

RG: What challenges do indigenous athletes face in mainstream Global Sport, including the Olympics, compared to those not from an indigenous background?

CW: Global Sport is driven by ‘national belonging’ and 'competition'. You have to accept it, if you want to play a leading role in it. Cultural sportive expression has nearly no space in it.

RG: Does indigenous representation of modern nation-states in sporting events help in reconciliation or represents a moral dilemma?

CW: Nearly all nation-states of our world are political and / or historical constructions. Sometimes, they represent dominant cultures of their territories or create new ones like the former USSR.

Indigenous representation inside nation-states at the opening ceremony of the Olympics in Tokyo mostly meant a domination of one culture over the other. Let us also remember that currently, 574 recognised Native American tribes are living inside the territory of the United States.

Physical expression of the diverse cultures around the world must be preserved and promoted, but cannot be squeezed into the systems of global sports that we know.